A little note at the start: there is a lot of discussion of death in this essay. There are mentions of torture, and I talk about war. There’s a lot about covid-19. There are also a lot of images of skulls (drawn images, no photographs). Finally, for those of you who’d like advance notice about entomological images, there is a photo of a cicada. It’s a long and looping essay, still a draft. Thanks in advance for your slow attention, but also take care of yourself and give it a miss if you need to.

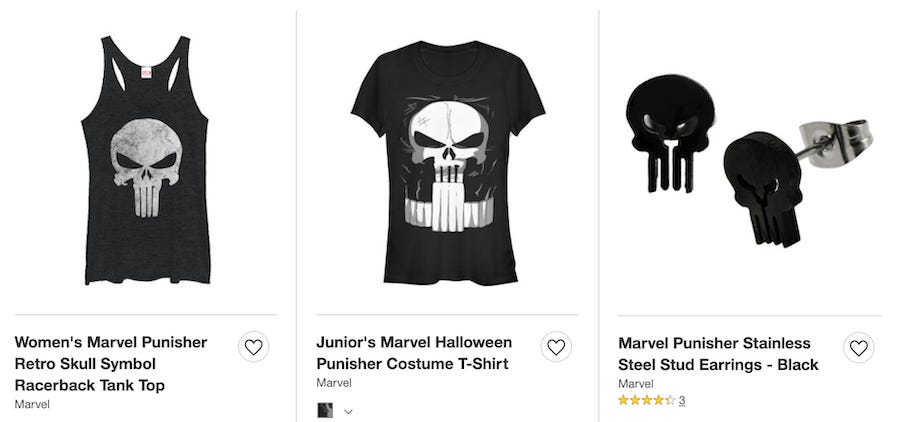

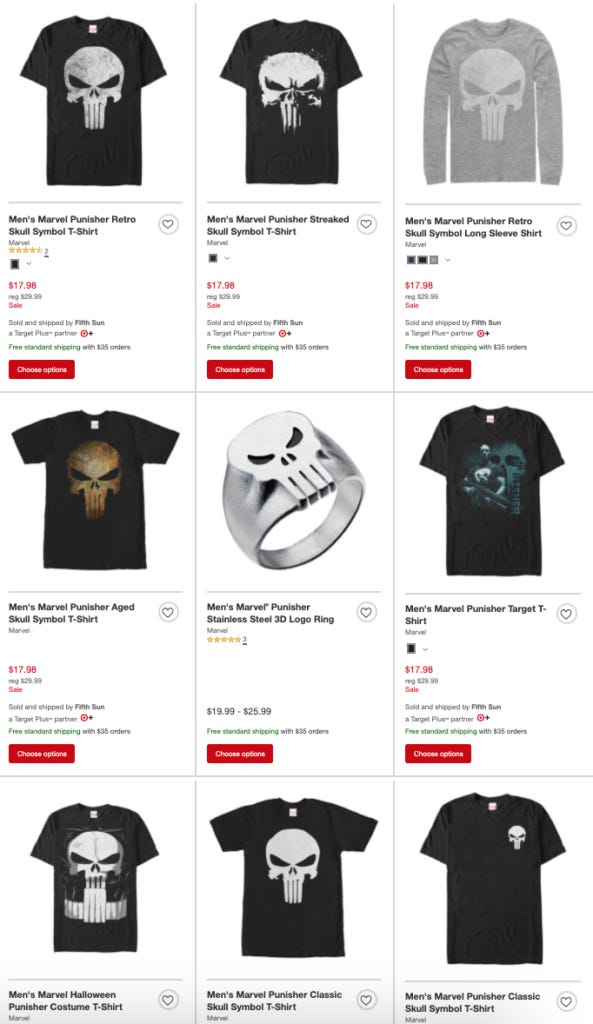

In Iowa, my place of residence for 2021-2022, the skulls are everywhere: on a child’s dress, white on gray. A sticker on a student’s laptop. On the back of truck after truck, the stylized skull that is the symbol of a comic book antihero, adopted by US soldiers during the second US war in Iraq, and then by neo-nazis and right-wing extremists and white supremacists and police supporters. They are printed on a student’s scarf, looped around her neck in a gesture that stops me in my tracks: a noose of skulls. The sign of death. The sign of the end of the world, poison, go-no-further, the limit of human person touching the limit of corpse, object brushing up against subject.

This isn’t a new motif. I remember when I noticed the skulls appearing, ten years ago or more, because when I first saw them I was shocked that anyone would wear a symbol of death. But there they were, on scarves and shirts and hats and skirts in H&M and Top Shop. They appeared about a decade into an endless war that only recently ‘ended’, and now I think of this motif as a way of processing all that was submerged during that time and has happened since: all the violent, horrific, dehumanizing death at a remove of thousands of miles, much of it carried out by unmanned drones. All the thousands of coffins coming back to the US with dead twenty-somethings in them, borne across tarmac without so much as a photo on the front page of the US paper of record. All the hundreds and thousands of children and women and men killed in places hidden from us by the same paper. So I started thinking about the skulls: about why they were still showing up, what underlying currents might cause images like these to bubble up in our daily lives like gas in a swamp.

The fashion industry moves so quickly, changes so quickly. Nevertheless, the skulls are still there. How is it that this image continues to appear? I find skull-print clothing in the children’s section at Target and think, isn’t this an old design? The child in the skull dress rides a hoverboard down the central Iowan sidewalk toward me, and I step into the grass so she can pass. The hoverboard takes up most of the width of the sidewalk. The grass has a little sign sticking out of it, a white sign with a green circle on it: Keep Pets And Children Off. Poison. Grass Has Been Treated. When I step back onto the sidewalk and into the shade, the air is cool even though the day is warm and the sun is high. September.

Arriving in Iowa in August 2021, the heat hit my whole body. In the evenings, cicada song was so loud that with the windows open the insects’ noise surpassed the volume of music and television. In August and through September I walked early every morning, when the humidity was high but the temperatures were relatively mild, and every morning I found cicadas smashed on road and sidewalk, both fifth instars and adult cicadas.

Adult cicadas’ wings are iridescent and stiff. Their bodies are colored like enamel, copies of Lalique cicada brooches that turn out to be actual cicadas. Instars are gray-brown, glossy, almost waxy. There were so many dead cicadas that I developed an ability to spot their carcasses in advance and lift my eyes enough not to see them closely, while also avoiding stepping on them. Cicadas are large enough that they seem to be individuals. It was hard to see them flattened or squashed or just upside-down and motionless in the street.

Early September is a beautiful time of year in the Upper Midwest, an island of crisp weather before a final week or two of high heat and humidity in the second half of September. Before our 2021 arrival in Iowa I had spent almost two decades away from Midwest autumns: the huge open blue skies emptied of humidity, the ragweed releasing its billions of grains of pollen. The monarchs, the milkweed pods. When I last lived in the Upper Midwest I was a university student, only a year or two out of my family’s house. Then, September mornings felt like total freedom. Those mornings, I could go anywhere on my bicycle, and the air would be crisp and bright and everything would be living all around me. My feelings of September freedom took place in the first few years of our endless war, which began just after the towers were hit by airplanes used as missiles.

It was a bright Midwestern September morning when 2,977 people died in a city halfway across that continent. That morning would be the beginning of thousands of retributive deaths in other places over two decades. But I didn’t know all that, on that Tuesday morning: I only knew bicycle, blue sky, September, Mississippi River shining wide beneath the Tenth Avenue Bridge, the cool dark in the university ballet studio before my eyes adjusted to the dimness. I remember that morning’s sky very clearly. I walked out of class with everyone else after the head of the dance department dismissed us, mid-barre. No one told us what was happening; it was only later that I began to hear. The sky was huge, open, empty. No planes flew through it. I lay on my boyfriend’s double bed all afternoon with him. We had seen the towers fall and the bodies fly from them as if they were paper, or doves, or some substance other than the unbelievable, factual substance of human bodies falling, leaping, from skyscrapers, through a September sky that was ash, ash, ash, ash.

In September 2021, I am an employee on a one-year contract at a small liberal arts college in the Upper Midwest. I ride to campus, lock my bike behind the library and walk to my office under blue sky. On my way, I cross paths with a male student, tall, white, soft curly hair, wearing a green T-shirt with an image of a snake coiled around an automatic rifle. (The Gadsden reference is clear.) Underneath the image it reads “COME AND TAKE IT”. I don’t want it, I think, reflexively. I just don’t want you to kill me with it. I realize as I think those words that to say them out loud might, in some contexts in my country, seem so laughably submissive as to be a provocation to violence—this country where we yearly revisit our most spectacular victimhood in order to justify a perpetual, universal vigilanteism that is hardly given a second thought.

The student with the snake-and-gun T-shirt isn’t in my class, but the feeling of the shirt is. When I collect my students’ writing exercises in the first week, about half of them contain a reference to a mass shooting—an imaginary one. The prompt was to write a poem, based on Allen Ginsburg’s “A Supermarket in California”, where something unusual or magical happens in a grocery store. The unusual event in many of their poems turns out to be gun violence, public death, terror: a mass shooting. It’s a small sample size, just twenty students at a tiny college in rural Iowa, but nevertheless I’m taken aback at the amount of space mass shooting takes up in their imaginations. Then again, they have practiced for such an emergency many times every year since they were small. The fact of public mass killings is so deeply embedded in their understanding of the world that they see them everywhere, even when they close their eyes and write. They live in a place where people who prefer for children and teachers not to die are made out to be a threat to “liberty”. But in the classroom I see that the threat of being killed reduces the liberty of my students’ imaginations. In a culture that worships death, the ritual and ceremony, the liturgy and its secret language, are performative speech acts. The words we use, the ways we speak, makes what we imagine real.

I often think about the student with the ‘Come and take it shirt’, or a version of him, when I’m working at a university in the US. Every time I’m in a classroom with young men in the US I feel keenly aware that, demographically, they could kill me and others in the room: for perceived slight, for bruised ego, for anxiety and grief badly handled, for unmet entitlement, for whatever reason or for no reason. This sense dilutes as the semester goes by; in the end, I believe in our shared human life, the one we make in classrooms together. I believe my students can transcend and make sense of their hurt, worry, and anger as much as anyone else can. I believe they have the right, as we all do, to struggle toward a liberating being-with-others. And I also know that some of them will not make it. I know they, as I do, live in a culture that is suffused with violence in service to whiteness and maleness, wealth and nationalism and a perverse practice of Christianity. I know that white and male rage and entitlement simmer beneath the surface of everyday life, emerging Vesuvial from time to time in spectacular displays of violence that are talked about as isolated incidents.

A mushroom also appears to be an isolated incident, but is an instantiation of a massive mycelial network submerged in earth, just out of sight. This is what I’m thinking about. How our cultural and physical bodies show that we know what is happening, even if that knowledge is pressed down, made unspeakable.

It is beautiful early September in Iowa, and the days are passing as if all our days are just ordinary days. But the calendar. of public life knows these days are not ordinary: they are the preparation for a public renewal of our national commitment to death. Since returning to the US in 2017 I have had to learn a new date in the calendar here. Watching “September 11th” creep up is like observing the approach of a religious holiday I don’t celebrate while living in an especially orthodox area. For some people—who lived through those events; family members of those who died or who were first responders or who lived nearby and witnessed those horrors; people who suffer under the US’s draconian surveillance policies and from vigilante violence against anyone apparently Muslim—maybe this yearly revisiting is meaningful, painful, deeply personal. Perhaps it is necessary for some people. In the case of those who had no body to wash, wake, and bury, maybe the yearly reappearance of this event in the public consciousness affirms that the unendingness of grief is unending: each year, at least for a day, everyone else is thinking about it again, too.

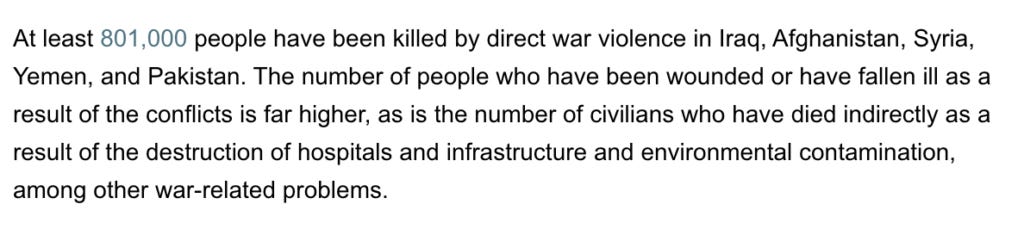

But in my case, each year, articles about “September 11th” in the week leading up to the anniversary take me by surprise. The papers print a yearly, national observation of the nearly religious, unstated principle “we will avenge your deaths”. But we the taxpayers of the US have ‘avenged’ those deaths hundreds (if not thousands) of times over, using missiles and drones and “the mother of all bombs” and literal decades of human life stolen by our torture and confinement systems. Every year we commemorate a relatively minor (in global terms) attack, and every day we are required to repress the facts of the minor and major attacks carried out in our names.

What I’m trying to say is that even as I bike to the college where I will teach under a clear and open blue sky, I realize that out of a sky like this has come, and will come, death for many people I can’t see; death I pay for with the taxes on the salary I bike to work to earn; death that is tallied up in an accounting that puts 2,977 lives on one side of a balance, and infinity on the other.

Biking home from the university one afternoon my eye is drawn to something in the road. As I get closer, I see, horribly, that it is a squirrel. At first, I think the squirrel is alive: it is lying on its stomach and its body is whole. But then I am just near it and I see that it has probably fallen from the huge tree that shades that part of the street, misjudged a leap and died on impact. It is gory. I do not want to have seen this but as soon as I have seen it I can’t unsee it, and I can’t unfeel the urgent desire to lift this animal out of the road and into a grave. I feel the same with the cicadas, and these I do often lift out of the way. But the squirrel I can’t—it’s too horrible, I’m too disgusted, and there’s the practicality of fleas and mites and how to move such a thing and where to, and on top of all this I’m in the road, on my bike. So I don’t do anything, and over the coming days as I bike by it it is flatter and flatter, drier and drier, until now, two weeks after the death of this animal, it is just a piece of leather and a stain.

It had been a whole being.

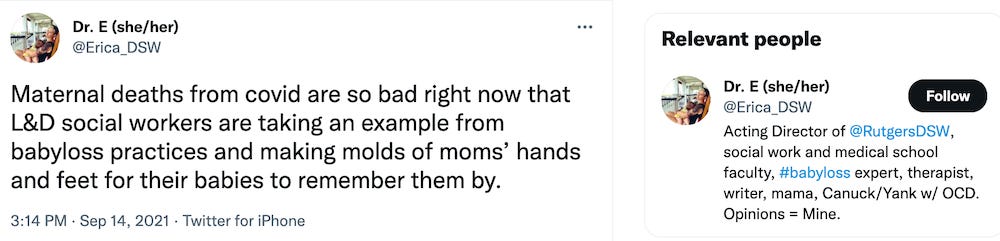

They had been a whole being. That’s what I find myself thinking every time I encounter one of the reports of people dying in intensive care of Covid-19. At this point, most of the reports are about people who are not vaccinated, and the undertones are wonder at ignorant carelessness or schadenfreude at what seems like karma but is just the fact of viral transmission in populations where some people have less resistance than others. The photos that accompany these reports are hard to look at: they show people subject to intense medical intervention. Some are intubated. All have IVs and other monitoring and medicating equipment attached to their bodies. Some have no clothes on, or almost no clothes. Alongside the reports of deathbed regrets or defiance there are also reports from the workers who have been taking care of people—who have been caring for people as they die, sometimes in great fear and often alone—over and over for the past three years, and who are exhausted, fearful, and traumatized themselves. All these dying people. All the nearly seven million deaths. All these nurses, doctors, janitors, cooks, assistants, and other workers in hospitals and clinics who have been going to work, day after day, not knowing what lay ahead but nevertheless going to work. Each one, a whole being.

Each year, when August ticks into September in the US, the number 2,977 floats through our newspapers, social media, radio. The number is something more than a number: it now stands for uncountable loss. The immensity of the figure is emotional and numeric. Emotional: all that loss, all at one time. Numeric: 2,977 flickers at the edge of countability and our ordinary capacity to conceive. We use numbers like that in daily life—price of a computer, maybe; a secondhand car?—but it’s unlikely that we know 2,977 people. In its immensity 2,977 is a reminder of the hugeness of perception, zooming out toward galaxies, and the minuteness of perception, zooming in toward atoms. Telescoping out, 2,977 is an untellable number of universes. Infinite details, possibilities, relations were lost when those people died. Limitless grief. Each one, a whole being. Telescoping in, 2,977 is a dot in a field of time composed of the death of every being who has ever lived. 2,977 is both a number of individuals and an integral number, unbreakable into component parts, at once a tally of each person dead on that blue-skied September day and a total from which perhaps few people beyond those directly affected can extract a single name trailing its complete, beloved ghost (a whole being). 2,977 is a number from which there is no return and yet a number to which the US as a country returns, religiously, each September. The idea is: the number is so huge. The shock of the huge number is enough to remind us of the shock of that day. Let there never be another such day, the number says, when so many universes are extinguished all at once. 2,977 is too many to lose.

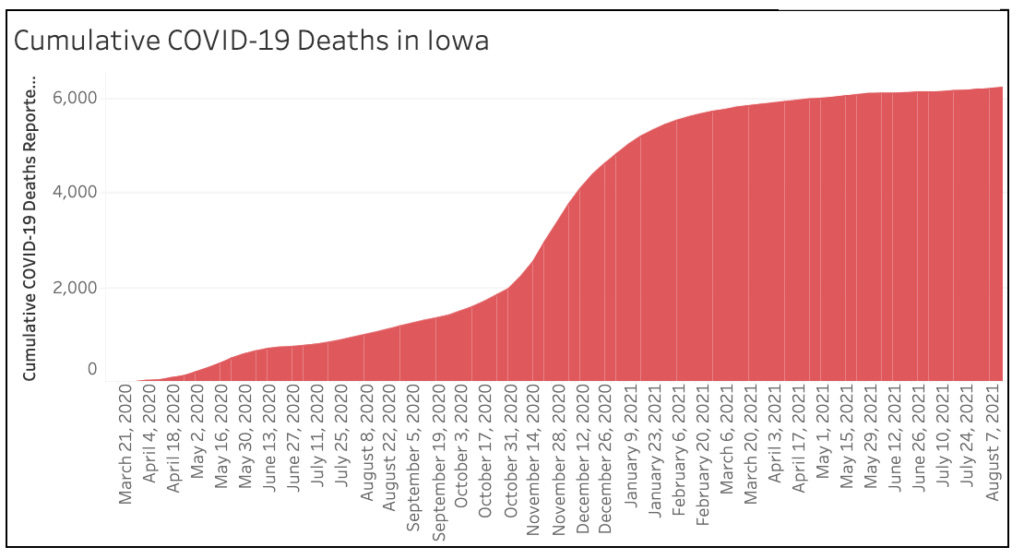

The day I first drafted this essay was September 10, 2021. In the United States, that week, 3,231 people died of Covid-19.

The average Covid-19 death rate between March 2020 and September 2021 in the United States was just over a thousand deaths per day. Every three days, on average, the number of deaths equalled those of that one September morning. But there has been no monthly, weekly, yearly national commemoration. There has been no massive mobilization of resources to face and rid ourselves of the cause of all this death. Instead, in much of the country, not long after the dying began, governors and legislators doubled down on the side of death, prohibiting common-sense public health measures, spreading lies, and letting a contagious virus run its course among poor, weak, sick, elderly, Black, Native, immigrant, and young people.

I read local newspapers as a way of understanding where I live and what is happening there. I love to know that there are church members debating about new windows, and that the local humane society is sponsoring a walk-a-thon, and how the recovery from a storm is progressing. The papers give me context and language for what I see as I walk through the place I live. In the comments sections of the newspapers I read during the first years of the pandemic (in two different towns in two very different places) I frequently encountered an argument that most of the people who had died of Covid-19 were elderly. The argument went, older people and people with underlying health issues are more susceptible to death in any case. And then it came to its flawed conclusion: being vulnerable in any case, these deaths are therefore no great loss, no great worry. We should get on with our lives as usual. Week after week in September 2021 I read comments with arguments like that one—more or less the same as that one—in the local papers. And the conclusion was almost always the same: that some people’s lives are simply the cost of other people’s comfort.

But each death is a death of a beloved universe. And each person suffering, being ill, being isolated, fearing—that is a whole person, however old, or disabled, or already sick. It seemed, reading these comments, that many people I lived among had decided that some kinds of life are no life at all; that there are whole categories of expendable people, generally unseen, whose deaths are permitted or even welcome in service to “life as usual”. We need to get on with our lives. Okay. But who gets to get on, and with what kind of life?

Imagine reaching a point in your very real, very whole existence when you knew that people around you considered you disposable simply because you…were elderly? Or couldn’t or didn’t have employment? Imagine living in a body whose “pre-existing conditions” (including the human condition of being born into a mortal body) meant your place in the great social calculus is the remainder, swept away as an unfortunate but unpreventable casualty of each new wave of economic life and human death. Solidarity relies on a public sphere in which each of us knows that even people we can’t see, even people whose lives look nothing like ours—lives that might have less mobility, less authority, less power—have an absolute right to those lives.

In the same newspapers, over the same period, many column inches were taken up with personal and official testimonies, remembrances, and oral histories of a national catastrophe two decades in the past. When is remembering an encumbrance of getting on with life? And when is remembering required for life to feel like it is going on normally? What is the “normal” life that we “get on” with when we return to a tragedy put to nationalist use? The character of “normal” life for the US since September 11, 2001, is the mass, ongoing death of people whose lives are figured as abnormal, or barbaric, or dangerous, or who are simply out of sight. Normal life in my country is the death of others in service to “normal life”.

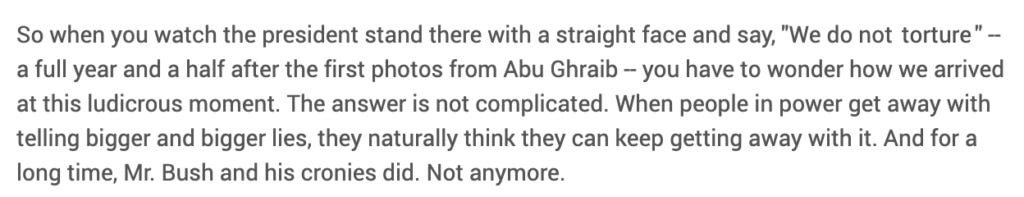

All along, as the days unspooled after the towers fell and in the two decades since, we in the US have been asked to remember some deaths: 2,977 of them. But this public demand is not the private remembrance of commemoration and grief or grief and humility or grief and solidarity; it is a publicly demanded, publicly performed and ritualized remembering that has been put to use for private profit and pillage, for murder and terror and impunity. We were asked to remember, but we were also asked to forget.

We were asked to forget that there were no weapons of mass destruction. To forget that bombs fall on real people, with houses, families, ideas, imaginations, pasts, futures, none of which likely included being killed by American weapons. We were asked to forget mass death, hundreds of thousands of people dying over the course of decades. We were asked to forget, as years went by, that we were paying for these deaths, and that in paying for a war we were also paying for critical infrastructure failures, both practical and interpersonal, that meant the deaths of even more people. And we were asked to forget that all of this was based on a lie, and that the lie meant a few people close to the president got very, very rich.

So our mourning moment was subsumed into support for or ignorance of years and years, decades, of war, all of which were happening so far away from most of us that, in the urgency of keeping body and soul together on a federal minimum wage of $7.95 per hour, we could forget, or we had to forget, or we simply didn’t know.

We have had so much practice in forgetting, as a country, and so much practice in looking away.

In his discussion of dreams, Freud writes that the dreamer suppresses the negative, latent content of a dream, and this content takes new, distorted, diluted, or unrecognizable forms. In dreams we may, like a child offered an apple she does not want, “[assert] that the apple has a bitter taste, without even having tasted it” (Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, 119). Through the process of displacement, fear, loathing, and other negative affects relocate to unrelated elements of the dream, while the actual target or cause of these affects may only glancingly or passingly appear. When negative affect is repressed, it is the work of what Freud terms the ‘Foreconscious’, which “reenforces […] antagonism against the repressed ideas” (ibid, 480). What is, however, does not disappear just because it is repressed. It emerges as symptoms. Freud is writing about sexual desire and about violence, how these manifest in the psychological activity of individual subjects. I’m thinking of Freud’s theory not as a diagnosis, but as a metaphor.

We in the United States are told we live in the greatest place on earth. We are told we are free, we are rich, we are powerful. The impunity our government grants our military to act with in places beyond our borders is doubled at home by our police.

The US military-industrial complex (both domestic and foreign) is inordinately wealthy. US parks are beautiful, US highways are wide. In the US, our grocery stores give us strawberries in January and ice in July. But like the dreamer whose sleeping mind displaces fear, rage, longing, desire, our minds repress what makes our comfort—the appearance of freedom and plenty—possible. And repression makes our minds comfortable: if we were to confront the mass death that underwrites “getting on with life” or “back to normal”, how would we ever sleep?

When the dreamer’s subconscious represses even the knowledge that there has been transfer of negative affect onto a banal target, that is not the end of the road for the affect. The fear, rage, longing of the dream’s latent content does not die, dissipate, nullify, or depart. It finds crevices. It squeezes through, returns to us in daylight. The great fear? Fear of death. The end of the world, enacted on us as we enact it on others. It comes through the cracks, looking for oxygen.

Since 2020, we have all lived in the presence of continual mass death. In the US, after a few months of relatively mild restrictions designed to curtail both the number and the normalization of mass death, people in important and visible positions decided that we could live with mass death on a daily basis. What do we do with that fact, as organisms? As a social organism? Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. What is the effect of this decision to normalize mass death in social terms? In bodily terms? In the terms of the images we make and live among?

The fact is that for the last twenty years in the US we have lived in the presence of continual mass death, albeit far from our houses and ordinary lives. For the last twenty-two years in this country we have also lived in the presence of continual mass death in high schools, elementary schools, nightclubs, grocery stores, movie theaters, colleges, sorority houses. For the last fifty years in this country we have lived in the presence of continual mass death sprayed from airplanes onto landscape, plant, water, animal and human alike. For the last eighty years we have been living in the knowledge of the mass death of the nonhuman beings whose lives are integrally connected to our own. We go on as normal: we go to school, go to the movies, go to the grocery store (where we buy fruit and vegetables and meat and grains). We pay our health insurance premiums. We love our children and our parents. We make our art. We bicycle to campus, watching for roadkill. And underneath all this normal life?

Each of us, one whole being.

Each one of us, in an us much wider than county, state, regional, national boundaries: a whole being.

The lives of everyone on earth touch the lives of everyone on earth: we know that intimately these days, as the breath in the lungs of one child enters the lungs of another, and the virus replicates. What happens to us when we forget this, our shared life? What happens when the knowledge of our shared life is pressed down by a thick forgetting of death, of the deaths of others elsewhere underwriting our “normal lives”?

The morning arrives, and the sky is bright and high and blue again, as it has been almost every day since we arrived in Iowa. September washes over the rolling hills of south-central Iowa, and over the pools in New York that are surrounded by the names of the dead. It washes over the hospitals where the ICUs fill up and doctors send out desperate messages looking for a bed in the city, the state, the region. What is to be done? Our jobs are calling us back; the economy is “fully open”. The few financial supports have ended, student loans are coming due, and we still have to eat.

We have to get on with our lives, and so we must somehow displace our fear and rage and longing and grief, our knowledge of the irreplaceable nature of each human on earth and our fear of living in a death-driven society. We find ways to tamp down our despair. We look away from the cicada and the squirrel as we head to work or the grocery store; we switch off the radio when the numbers for the day’s fatalities are reported. Eventually we can feel that things are normal again. But like anything repressed, the fact of mass death and the culture that relies on it will find places to emerge. It makes its way toward the light of day.

Thank you for reading.