Harumi Abe: A Stone, a Universe

New paintings by Abe at Washington, D.C.'s Terzo Piano Gallery (until 18 March)

A garden manual called Sakuteiki, written by the 13th century and still in existence, begins the work of making a garden with an instruction for the setting of stones: to set them correctly, the text goes, you must first have a sense of the whole garden. The world is implicit in each element, the instruction implies; not only in the finished array, but in the siting of the first part. Every finished thing grows from the relations between each of its parts to what is around them.

The history of gardening is a history of the relation between the large and the small, the uncontrollable and the at-hand, the manageable and the unimaginable. The garden is a universe in miniature, a version of the world that can be surveyed and cared for even as the world outside the garden's gates unleashes disaster or veers toward human-made catastrophe. In the garden, and likewise in the landscape painting, we have a world that at is at once contained and transcendent. The garden points to the universe; the stone to the entire vista.

In Harumi Abe's paintings, on view at Terzo Piano Gallery in D.C. until the 18th of March (extended), this principle of relation between small and large is at work. Abe's fascination with making painted landscapes has been with her since childhood—in conversation, she recalls a landscape painted in elementary school, which remains, in her memory, in conversation with her adult work. Her primary genre over the past ten years has been the landscape, both remembered and observed.

The history of garden-making and landscape painting share a resemblance. The 13th-century garden manual was at first a manual of secrets, to which only the wealthiest or most privileged had access. The tradition of western landscape painting begins in parallel with capital's earliest accumulations, becoming a way to capture, keep, and display the spoils of empire and colonization. To Abe, however, a landscape is not a thing to be looked at so much as it is a system of relations she attempts to capture in paint. In her work, the landscape painting meets the garden in the space of everyday life. Both will teach us and delight us—and, sometimes, bewilder and terrify us—if we will only let them.

In conversation, Abe considers her current and past work, thinking through the sublime, the beautiful, the picturesque. She draws relations between how she makes her paintings and her life as an immigrant to the US, as well as to having grown up in Japan, in a family where art was always present. "My mother's father was an artist," Abe tells me, "and my mother wanted to be an artist, too, but her mother sent her to school to be a seamstress." The relation between artmaking and the practical world of housekeeping and family economies seems central to Abe's own work, an undercurrent through her paintings' process.

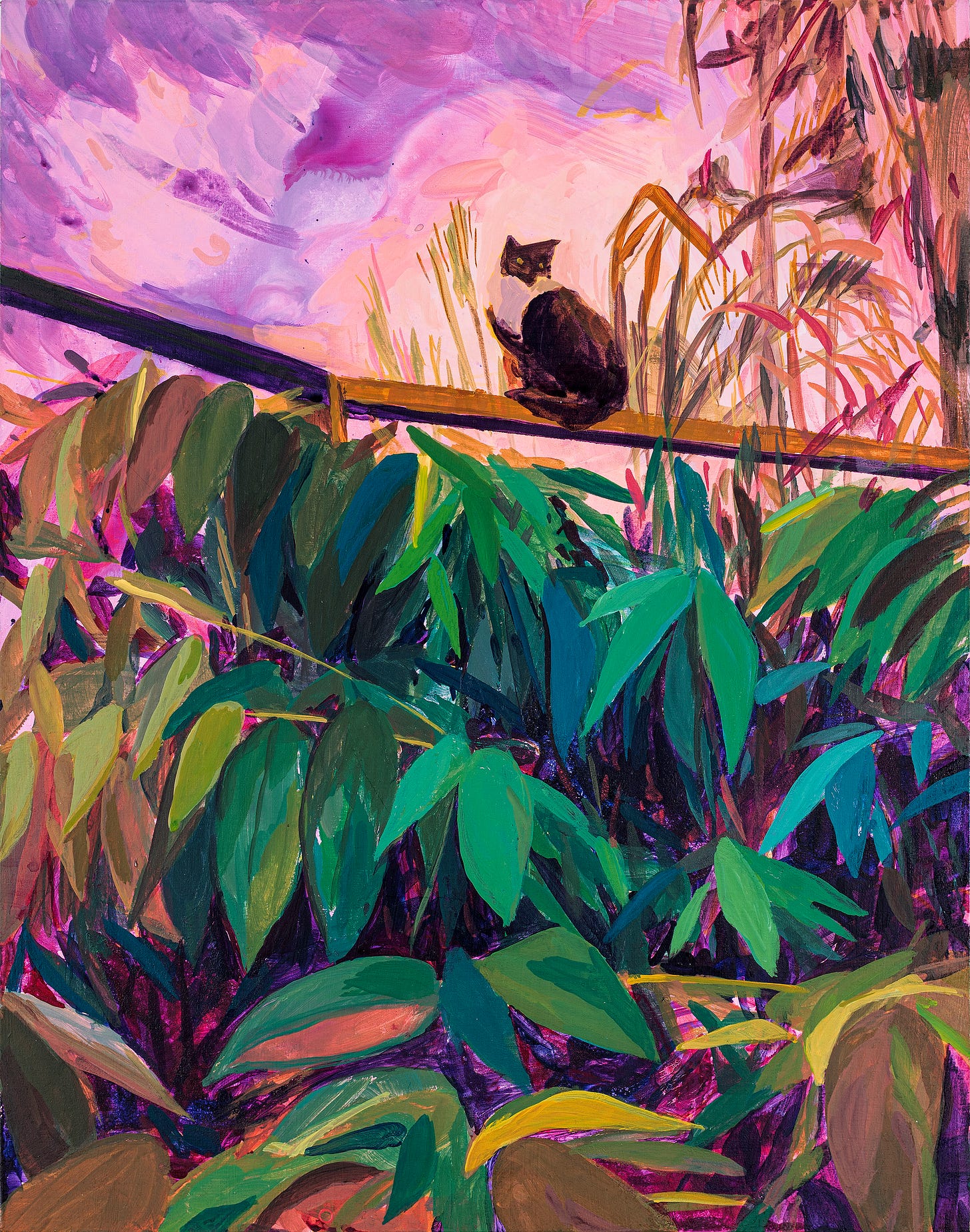

Abe is interested in the relation between ordinary life and artmaking, between domestic landscapes and the landscape painting. Her paintings begin as photographs taken in her home garden, where she grows cucumbers, tomatoes, mangoes, bananas, loofa gourds, and much else—or they begin at local parks where she and her husband take their daughter to play. These locations are not incidental to Abe's work: they are central to it. As an artist who is also and equally a parent, she has made a decision to make art where she makes her life. Like the stone that calls up an entire garden, Abe's close gaze at her most immediate surroundings offers her paintings a way to think about climate change, natural disasters, the relationship between our human lives and the lifespan of galaxies, and the process of birth, life, death, decay, and rebirth itself. All these questions, and the question of what landscape painting can be, have entered Abe's work as she attends to the landscapes that are closest at hand. "Paradise is within reach," she tells me, clicking through a few slides, remarking on where she took the photographs that led to the paintings. "What we might think of as 'heaven' is part of our daily lives. I want my paintings to remind us that what we see is precious. Everything is alive, and everything dies. We have to pay attention."

In earlier work, Abe's paintings spliced remembered landscapes from her family's home in Japan with the experience of living in Florida's subtropical surroundings. In these paintings, the 2011 tsunami moves like a nightmare through villages overlaid with Floridian vegetation. The devastation of the world interacts with its preciousness: beauty and terror together. Abe has long thought about the question of sublimity, but sees her newer work as a movement toward Gilpin's picturesque, where beauty and sublimity mediate one another. This reflects her own temperament—"I am a generally non-confrontational person," she tells me—but also a recent interest in the history of Buddhism. "The Buddha said that it was better not to go to either extreme," Abe tells me. "Good and bad, everything is dependent on everything else." She sees her new paintings as trying to find a way of depicting landscapes that neither ignores the ferocity and harshness of nature, nor dwells exclusively on it—and modulates similarly in response to aesthetic pleasure. It's about being able to see both the beauty in a garden and the human fear of the uncontrollable in it, she explains.

The paintings Abe has most recently been working on combine her attentive depiction of plant forms with poured, dripped, and dragged marks that recall the images of galaxies sent back by deep space telescopes. The south Florida coast offers a setting that is rich in texture and color, which Abe brings into her paintings. But as she described to me the experience of seeing a NASA spacecraft take distant flight while on a nighttime bike ride not far from her home, I could see that the Florida landscape's effect on Abe's paintings is not only present in the lushness of her colors, the brilliance with which she paints light, or the way palms and other local plants appear across her work. It is also evident in how space exploration has entered her metaphorical and imagistic imagination. In the newer series of paintings, images of galaxies ground the arrays of the Floridian plants that appear as a constant in the last decade of Abe's work. When I ask about this, she replies, "I have been thinking about the way I am an 'alien' here. I have an 'alien' card. I am not naturalized. But I have found a way to live in this landscape." The galaxy bursts through the palm grove; the nebula becomes fertile ground for a constellation of orchids. A stone, in its proper place, predicts a universe that forms around it. The landscape painting holds a glimpse of paradise still for one moment, so that we can recognize how ephemeral the beauty of our everyday surroundings truly is.

Harumi Abe, “A Stone, A Universe” at Terzo Piano Gallery, 1515 14th st NW, Third Floor, Washington, D.C. Until March 18; check website for opening times. This exhibition was reviewed in the Washington Post here.