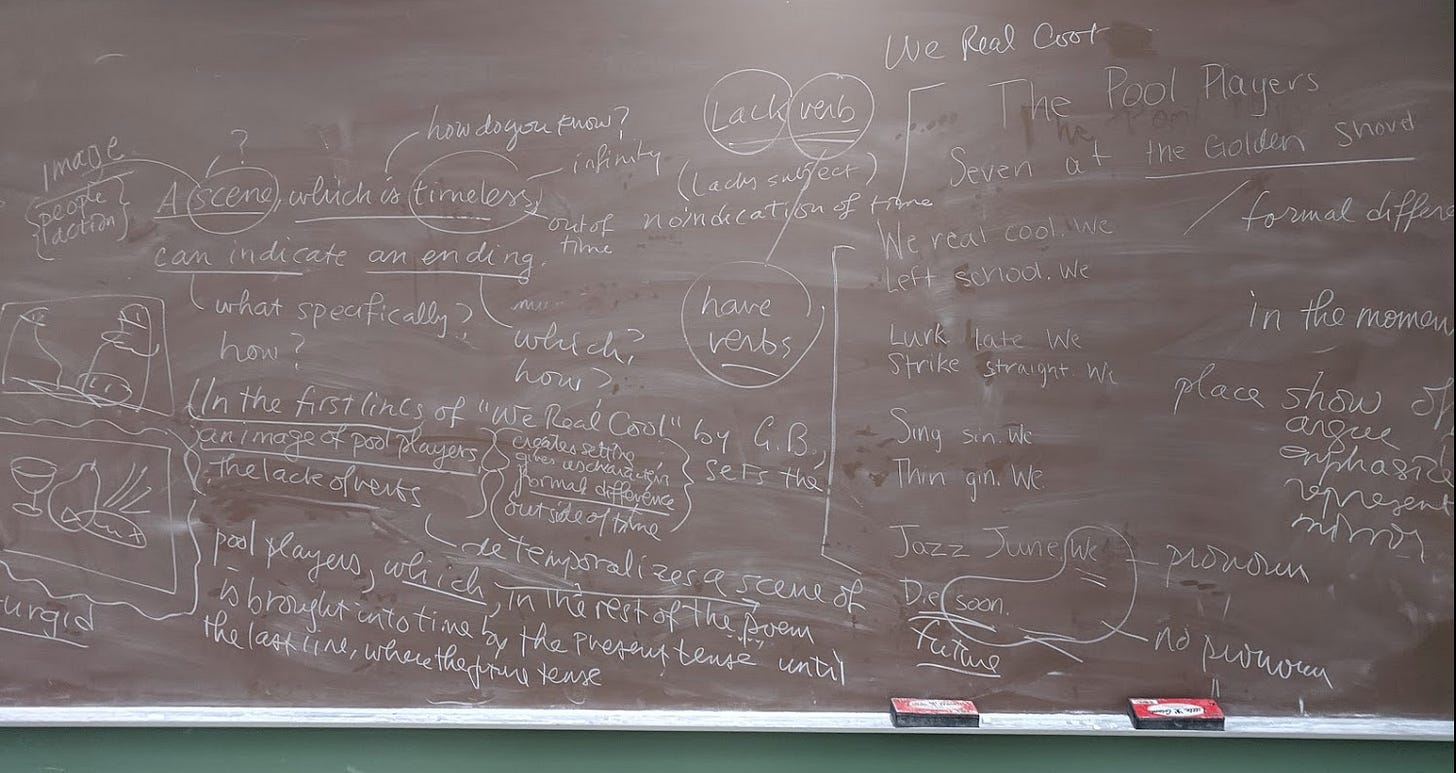

This semester, I had the uncanny experience of listening to a student give a presentation that had been generated by a large language model. (The contribution of the LLM was not acknowledged by the presenter. It was made clear by the kinds of factual and conceptual errors in the presentation.) In the assignment brief, I had asked each student to choose a book of poems, talk about the poet and their work in general, then read a poem closely to teach us some new element of poetry-making, and finally to design a writing exercise that the class could do in order to internalize an element found in/through that poet’s work. Please enjoy this, I said as I went over the assignment. Treat it as something that can teach you how to broaden your own writing. Focus on what moves you—you will do best by allowing yourself to find pleasure even in what’s unfamiliar.

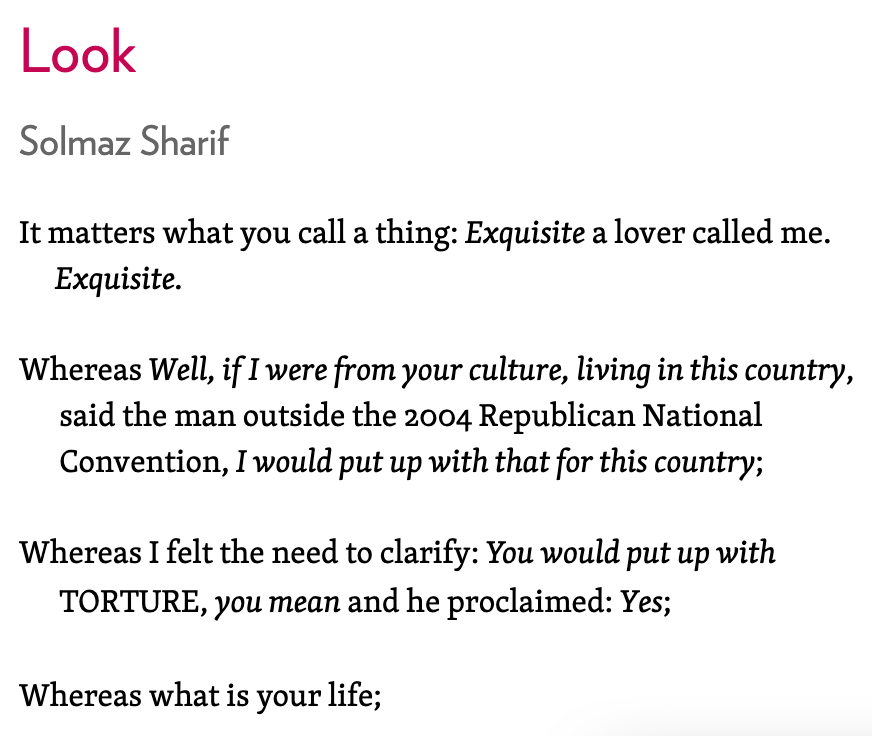

Writers know that words matter. Words make things happen in us and to us. They make things possible, imaginable, and real. They do things to us. They are material objects in a world where we, too, have material being. It isn’t magic, the way words act on us, and doing things with words isn’t magic either. Both are the result of the lifelong, sustained attention that happens in our everyday encounters with language. And really it isn’t the end point of those encounters (the moment where words do things) that matters the most. After all, we talk and write and think and sing and promise and so on over and over through our lives. Using language, we don’t arrive at some point where what we mean is what we Mean, all by itself; instead, we keep on unfolding the what-is-this-doing-to-me and what-do-I-meanness of language in relation to all the past unfolding of it. And that’s how the words we use do things to us: not by jumping out from behind a lamppost, fully formed and perfectly expressive, but by, one after another and one next to the other, constructing the very things it’s possible for us to think.

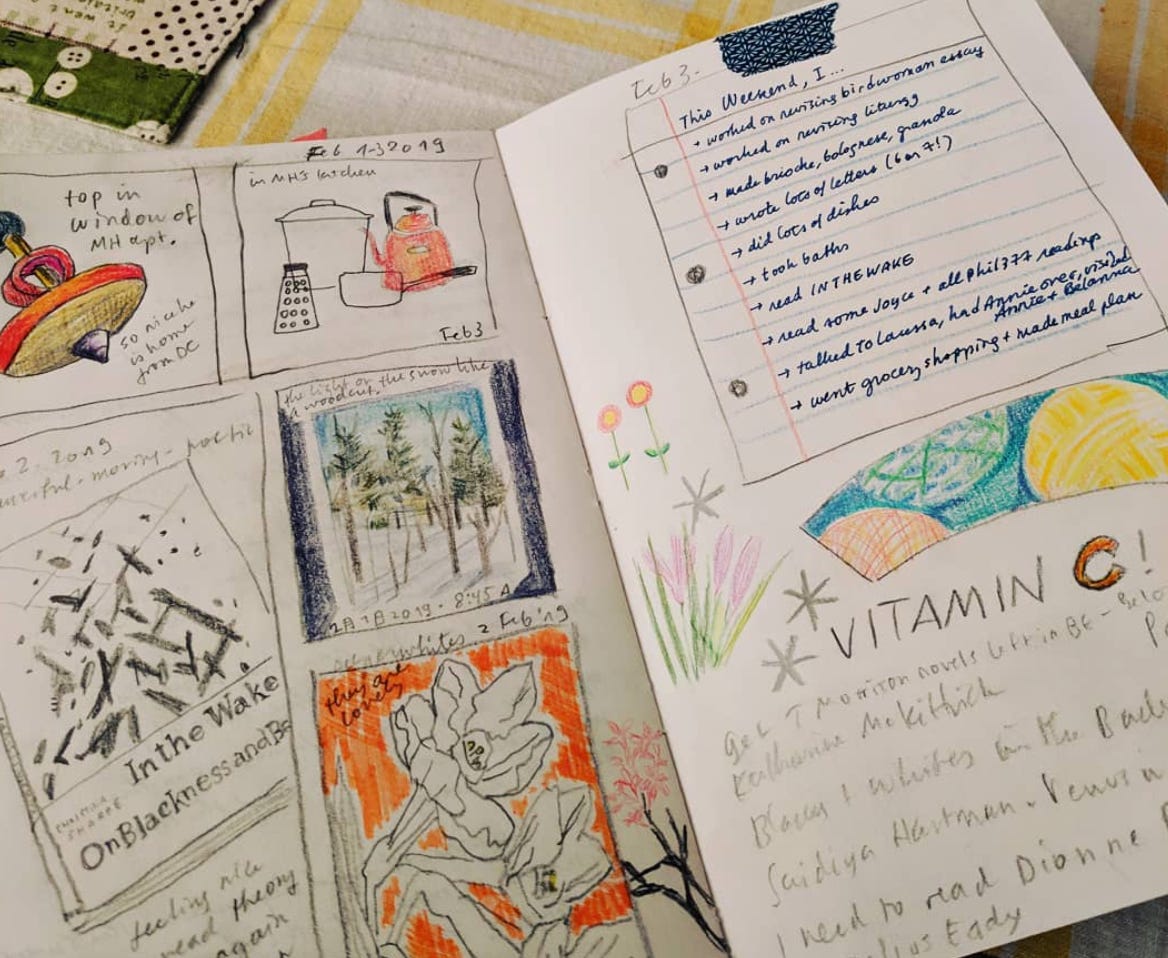

In the writing classroom in the past few years I have noticed the urgency with which some of the beginning writers I work with want to “be a writer”. Maybe it’s more like “Be A Writer”. “Being A Writer” means to have arrived: to be Someone: to have people pay attention to you: to be affirmed. It’s seemed to me very linked to the way that social media presents page after page of completed objects (craft projects, books, babies, houses, lives). Process is invisible; product is immediate and enchanting. Like like like like like. There is no shortcut, I have to say, gently (to myself, too). And there may never be success, affirmation, attention except from the peers with whom you cultivate long and meaningful relationships, the people who will, like you, say this matters about the confounding, slow, sometimes sad, sometimes tiresome, sometimes exhilarating process of finding out how to do things with words and how words do things with you. The people around you, this place here—the page, the classroom—this is it. We are here. You want to be a writer? Be with us, writing, here.

I think that especially in writing classrooms—and in all kinds of contexts where we are talking about how ideas happen, what kinds of people get to make art, how it is that art gets made, and how long it takes to think and make things well—it matters what kind of language we use to talk about the world around us. It matters that we think about what we mean when we say “thinking” and “creative” and “innovative” and “important” and “freeing”. It matters that we think about what we mean when we say “alive” and when we say “person”. It matters in part because words like that direct our attention.

Really what I’m thinking about here isn’t the student who chose not to do an assignment, or to do it poorly; we all have priorities. My mind has returned over and over since the presentation to the question of why they would use a large language model, instead of just not preparing and half-assing it on the day, or faking it some other way, or even coming to talk to me about why they didn’t want to do it—an option I made available. Why a large language model?

I think it is in part because of the way that in the writing classroom, in the world of social media, and in the imagination of student writers, writing can come to seem like a zero-sum game: the more I’m a writer, the less you can be. The more I’m a prize-winning poet, the less you are. The more I’m published, the less you’ll be. The more favor I curry, the less there is for you. This sense that there just isn’t enough to go around, and that there is a single and identifiable end point to aim for (and beat others to) deadens invention, subordinating the messiness of finding out to familiar routes toward a recognizable object that repeats the features of what we already know as “poem” or “novel” or whatever. It makes it seem like there is some thing out there that “writer” or “writing” is, and we are racing for it.

The choice to use a large language model to make work must also be to do with how LLMs are talked about right now, too: “intelligent” and “efficient” and “magical” and “low friction” and “resource-light”. I borrowed login credentials for a popular version and input various parts of the brief, but what came out was not “intelligent” or “efficient” or “magical” or “low friction” or “resource-light”. It was generic and factually incorrect and dull. And it didn’t even have the benefit of the dullest parts of my own writing, which is that I have done them and by the end, ideas have begun to arrive. Furthermore, it was not ‘low friction’; the companies that built it exploited workers in Kenya to filter vile content out. And it was not ‘resource-light’; it cost a liter of fresh water for me to ask it pretty frivolous questions (in the scheme of things), and it took almost 700,000 liters of fresh water to train the large language model. There are places in the U.S. (where I’m from) that have not had reliable clean water for years. Millions of actual, living intelligences (human and not) deprived of that necessary element. This is not a neutral thing, to use fresh water for something other than life.

“It matters what we call a thing.” When we use the word ‘intelligence’ for a program that runs statistics, more or less, to come up with combinations of words that occur predictably in such-and-such a genre of text, we allow ourselves to forget that intelligence is a composite of error after error; we forget that error comes from the Latin verb for ‘to stray’ and does not mean bad but wandering. When we use the word ‘creativity’ to mean the instant production of something that has the appearance of a work of art, we efface the fact that creation is a process, one that is responsive to material and to our own associative, sensitive brain-bodies, that reveals itself as we engage in it. We lose out on the learned-by-doing knowledge that, among other things, shows us thinking takes time.

After all, it isn’t just the getting-there that teaches us, or that’s valuable. Writing with our hands matters. Knowing through our bodies matters. Knowing material matters. Knowing via the human processes of making matters, not least because metaphors take their sense from our encounters with real materials and relationships. Time spent using our bodies matters in ways that are rhizomatic and may show up in ways we can’t predict at all. To use the shortcut of a large language model may cause us to miss something fundamental—including that thought is an embodied and emplaced process, not distinct from the outcomes of thought. A carpenter knows how to make a staircase in part through the embodied knowledge of the depth and height of stairs all their life.

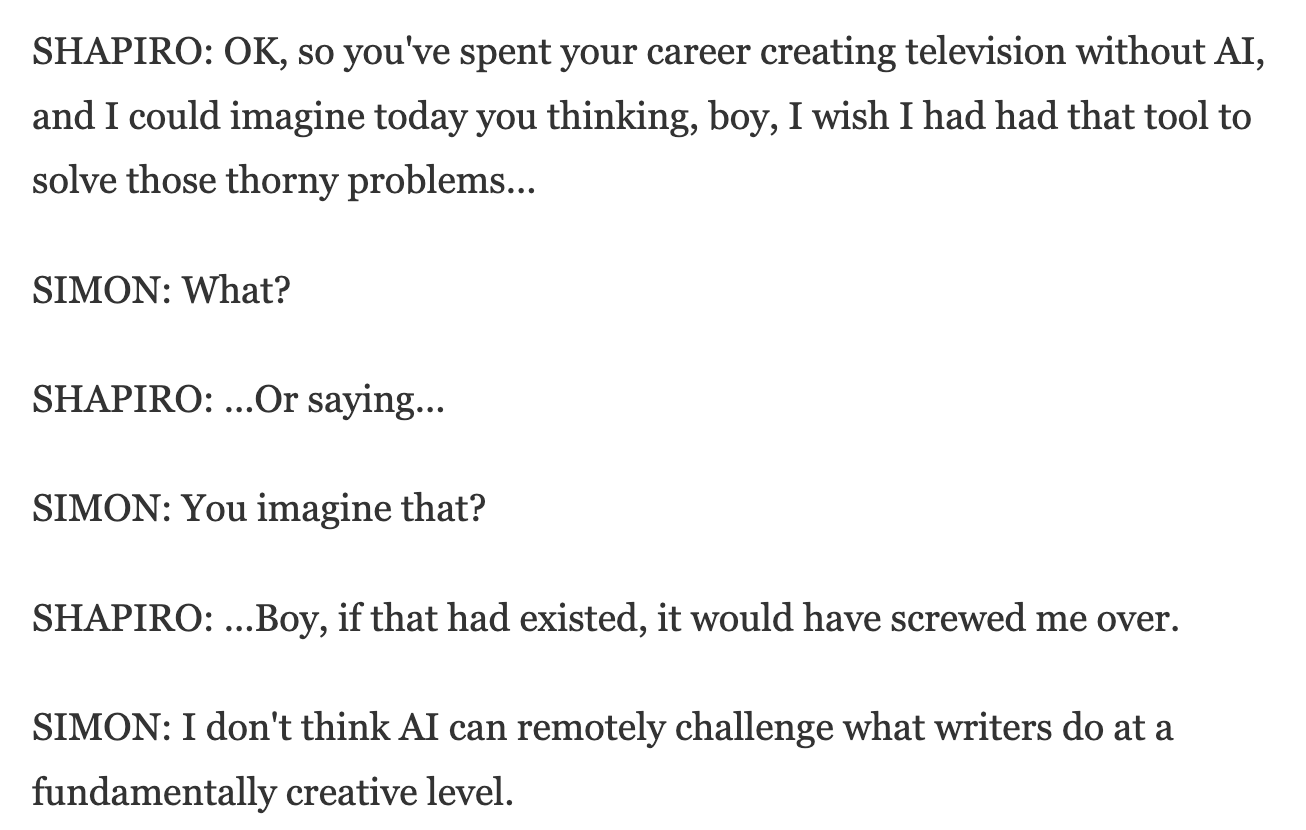

The way LLMs and other “time-saving” devices/scams (social media, all kinds of multi-level marketing programs) are presented makes it seem like the end is the point. Produce more. Win more. Make content and get some consumers. Who cares how; it’s the result that counts. Get more done, faster. Get through the “parts that don’t matter” and get on to the good stuff. Better yet, get someone else to do the parts that don’t matter for you. Cheap, easy, quick, and just as good as a human could do, or good enough because no one’s really reading, right? It’s so deeply cynical and so sad to me. I can’t quite tease out the relation among these things but it seems rooted at once in intense anxiety and competitiveness (both often fueled by an approach to teaching or talking about writing that focuses on ‘success’ in worldly terms—publication, recognition—that relies on scarcity) and in a slick, scammy understanding of the (literary) world wherein everyone around one is a mark.

But in any case, the way large language models are talked about in traditional media and on social media sure might make it seem like you could skip to the end of a ‘creative writing education’ and get right to Being A Writer without anyone being the wiser; certainly without hurting anyone. What’s more, you could especially skip the things you’re not used to, the things that seem like they’d bore you or ‘be pointless’, and you’d still have the result, which is (the semblance of) Being A Writer. But the “parts that don’t matter” are the good stuff. They’re all there is. The whole thing—the whole life thing—is finding out that something you thought might bore you didn’t, or finding a way to turn a constraint into an engine, or figuring out that you can do a thing that seemed impossible at first. Over and over. Writing is not only the arrival at meaning but the struggle through meaning toward meaning to understand at some point what one thinks. And then again.

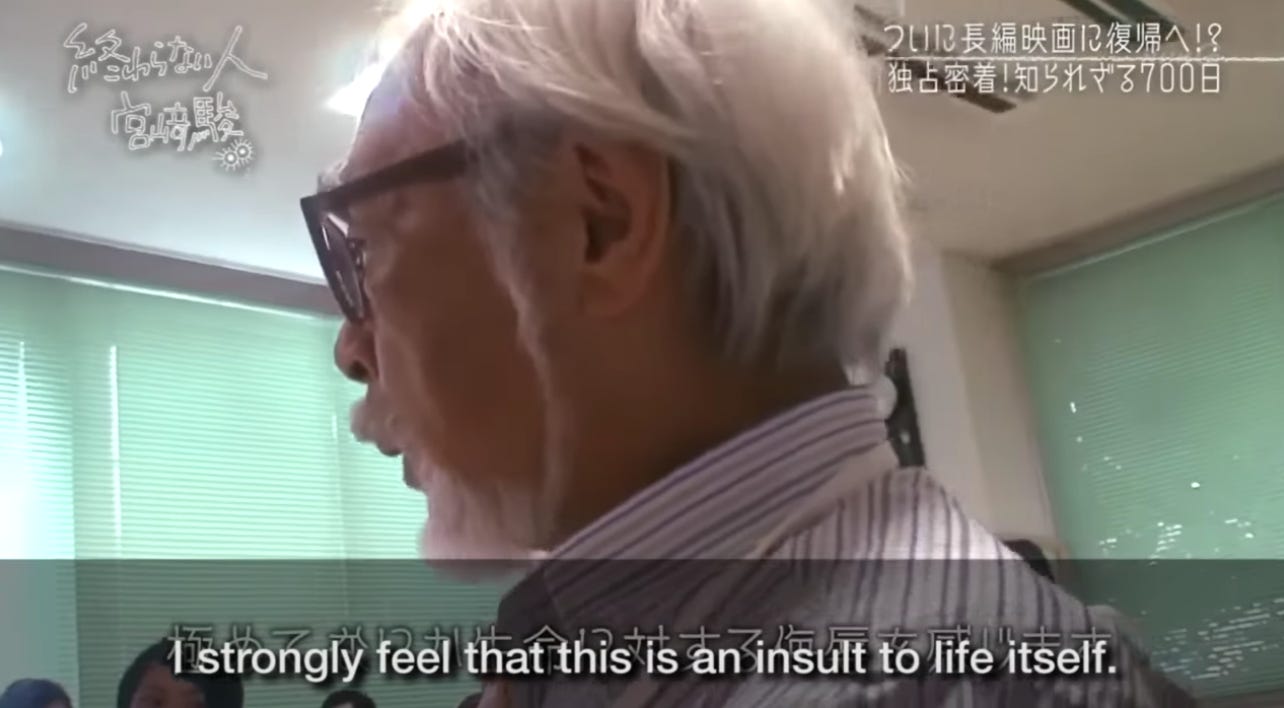

When Hayao Miyazaki says, in response to a team of developers who have shown him an “AI”-generated moving image of a distorted body moving as if in pain, “Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is. […] I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself”, I think he is responding to exactly the skipping-forward approach that LLM technologies permit. Skip forward over discomfort, unknowing, error; skip forward over encounter with (in Miyazaki’s example) the deep, real, embodied experience of one’s dearest people living with pain. Skip forward over grief—and also love, like Miyazaki’s love for his friend that allows him to notice his pain. Skip forward over the time it takes to think, which lets us think about where we are, and what it means to be there, and who else is with us, and what ‘with us’ means….

To skip forward this way is an insult to life because life is not an arrival at some peak or other. Life is the ongoing, unfolding, responsive act of being one among other finite beings, knowing they are infinitely precious because absolutely finite. And art? Art is the process of taking that knowledge of finitude, which sharpens and becomes more complex all our lives, and trying to make sense of it both alone and with others. The computer that the developers mention near the end of the clip, that could draw pictures as well as a human could—that probably exists now. But to think that technical skill is what makes art “art” or plenitude of ideas is what makes writing “writing” neglects the heart of these meaning-making pursuits: it is not the picture that results that is the thing called “drawing”. Drawing is the lifelongly act of learning to see and to connect the eye and hand. The end is not the point. It’s the long middle that matters.

Thanks for reading.

!["3.4 What is the extent of water consumption by Chat GPT, and how does it compare to other AI models? Chat GPT, the OpenAI language model, has been making headlines due to its impressive capabilities in natural language processing and machine learning. However, it has also come under scrutiny for its water consumption, and questions have been raised about the extent of its water use compared to other AI models. According to a report, Chat GPT consumes approximately 500 ml of fresh, clean water every twenty to fifty questions. Although it may not appear to be a large[27] volume of water each time, the fact that Chat GPT has over 100 million users monthly and is consistently responding to queries and producing answers accumulates quickly. It is estimated that during its training, Chat GPT consumed about 700,000 liters of water, which is equivalent to the amount[15] of water used by an average American household in about 20 years". Source linked in caption. "3.4 What is the extent of water consumption by Chat GPT, and how does it compare to other AI models? Chat GPT, the OpenAI language model, has been making headlines due to its impressive capabilities in natural language processing and machine learning. However, it has also come under scrutiny for its water consumption, and questions have been raised about the extent of its water use compared to other AI models. According to a report, Chat GPT consumes approximately 500 ml of fresh, clean water every twenty to fifty questions. Although it may not appear to be a large[27] volume of water each time, the fact that Chat GPT has over 100 million users monthly and is consistently responding to queries and producing answers accumulates quickly. It is estimated that during its training, Chat GPT consumed about 700,000 liters of water, which is equivalent to the amount[15] of water used by an average American household in about 20 years". Source linked in caption.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F60f8ad2e-52d8-44a6-b3c7-849b943cae54_1912x1228.png)

Gorgeously written. Thank you for this!

"It's the long middle that matters" -- nothing could be more true, and going through that long, lonely, often muddled, doubt-filled, tedious, and sometimes exhilarating middle passage of any worthwhile project (including life itself) requires curiosity, determination, and trust that the process itself is teaching us more than the end product may hold or reveal or "reward" us. Thank you for writing about this so clearly, and with specificity.