Hello everyone—it’s the end of May and this is your May installment of Bewilderment. Some beauty this month: audio recordings of classes in the Naropa University Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics are in the Internet Archive. In Minneapolis, four years on, George Floyd Square is still there. Something called Feral Atlas: do I understand it? Not completely. Is it cool to look at and around? Yes. Aster of Ceremonies by JJJJJerome Ellis is an exciting expansion of books’ and poetry’s do- and be-ness. Are you an artist (broadly defined) in the Minneapolis/St Paul (MN) area? You can submit your services for listing in the Late Night Copies Press 2024 Artist Directory until June 15.

If you’ll be in Dublin in June, this should be a good show.

Nicole Antebi, Éireann Lorsung

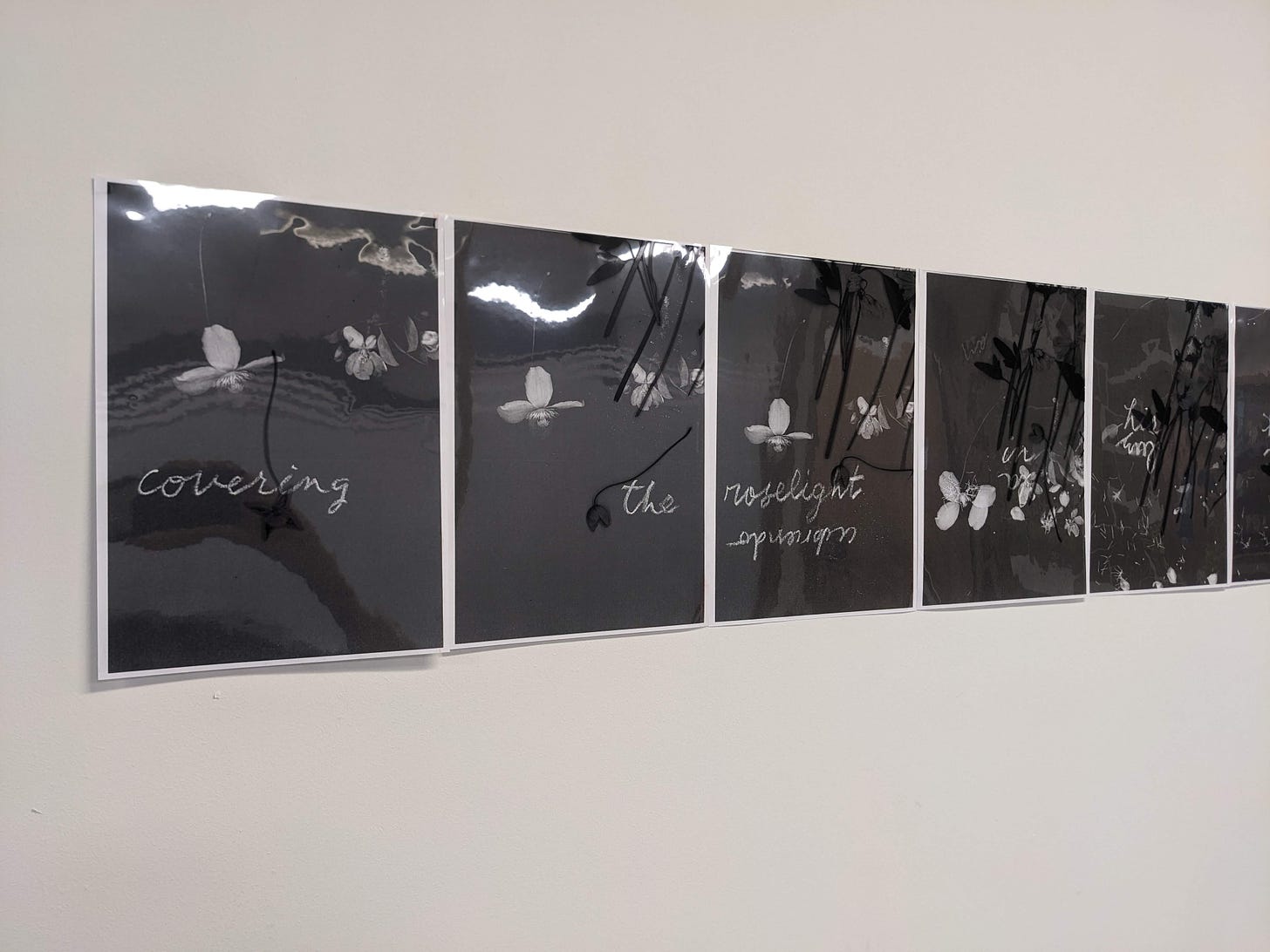

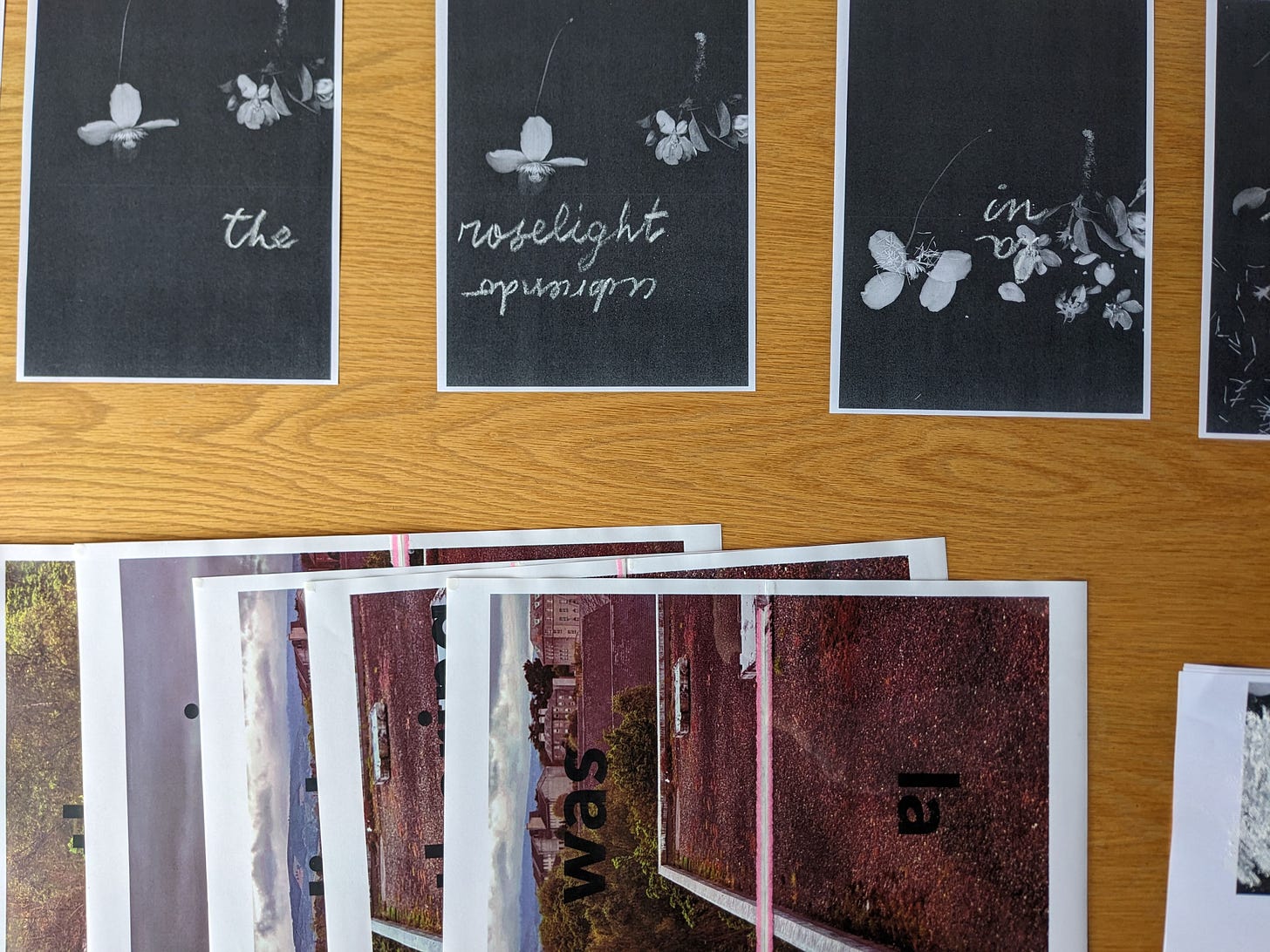

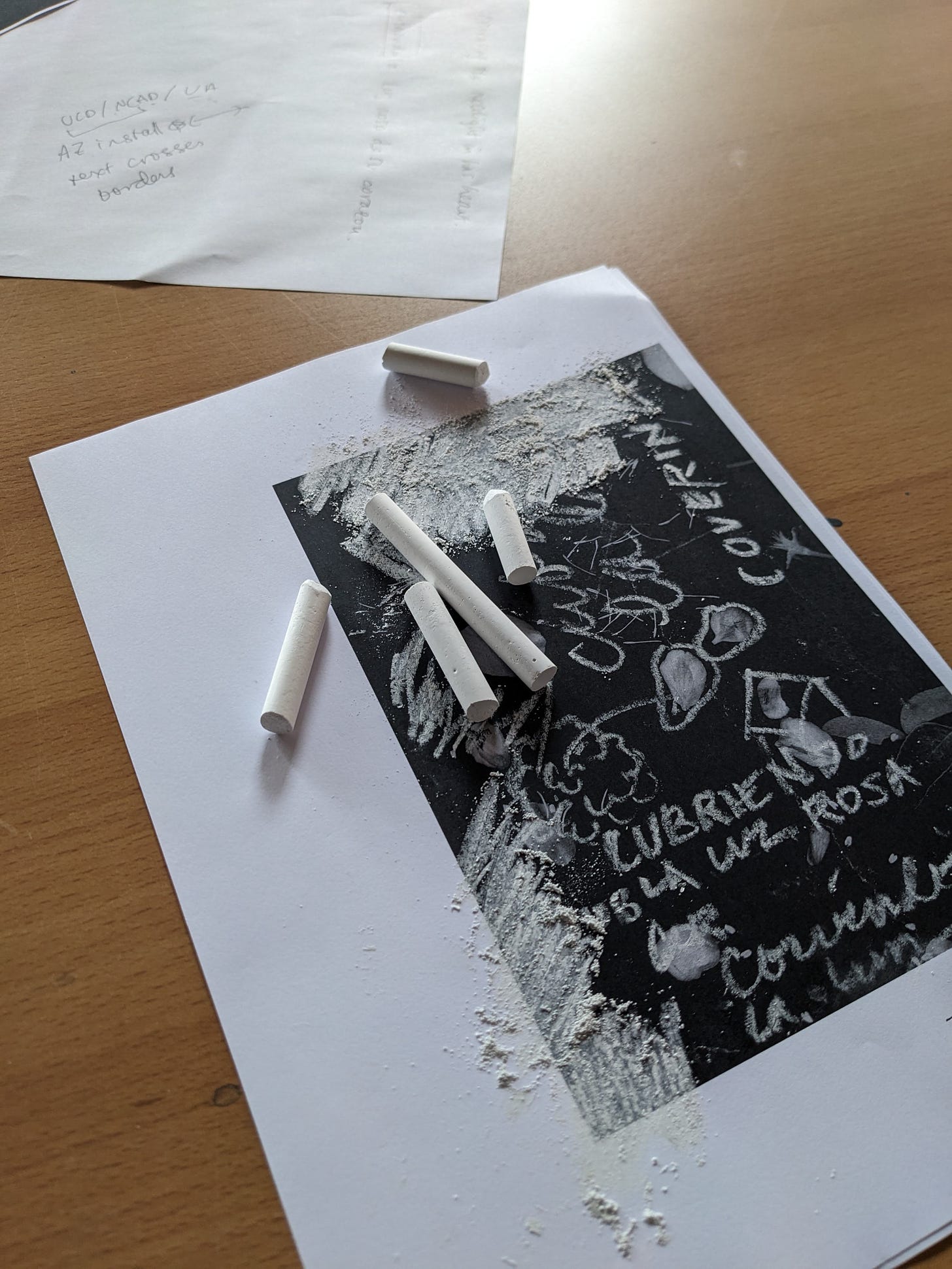

Covering the roselight in his heart / Cubriendo la luz rosa de su corazón (2024)

Animation, plant matter, acetate, paper, chalk, text, light, institutional constraints

Edition of two

The text of this piece comes from James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and its Spanish translation by Pablo Ingberg. Two identical pieces were made, one to be installed in Dublin, Ireland, and the other to be installed in Tucson, Arizona, US, the places where each of us lives. Covering the roselight…/Cubriendo la luz rosa… has as its ground an animation of plant matter gathered in Dublin. The animation was produced using a photocopier. The “lag” of the translation (the English text begins before the Spanish translation, and the translation ends after the original) speaks both to the time involved in translation and the time involved in animation.

The animator, filmmaker, and artist Nicole Antebi and I made this piece and one other in early May, on a gray day, in the southern part of Dublin, in a university building with a view of mountains in the distance. The text above is what we said about one piece we made together, and it’s true. But what couldn’t we fit on the labels we hung next to the pieces we made and installed?

We began planning to do something together a long time ago: maybe four years ago? We talked on the phone. We did things in our separate places, responding to one another. We had video chats across a continent. We had video chats across an ocean. We looked at one another’s work. We talked about what it means to make art. We talked about working in universities, both our histories of uncertain and underpaid work in them and our presents of relatively secure and well-paid work in them. We talked about animation and poetry, language, time, and borders. We continued to make the things we make: drawings, animations, poems, movies, things made of language and things made of images. We realized there is a lot of overlap among and across these.

Nicole Antebi, Éireann Lorsung

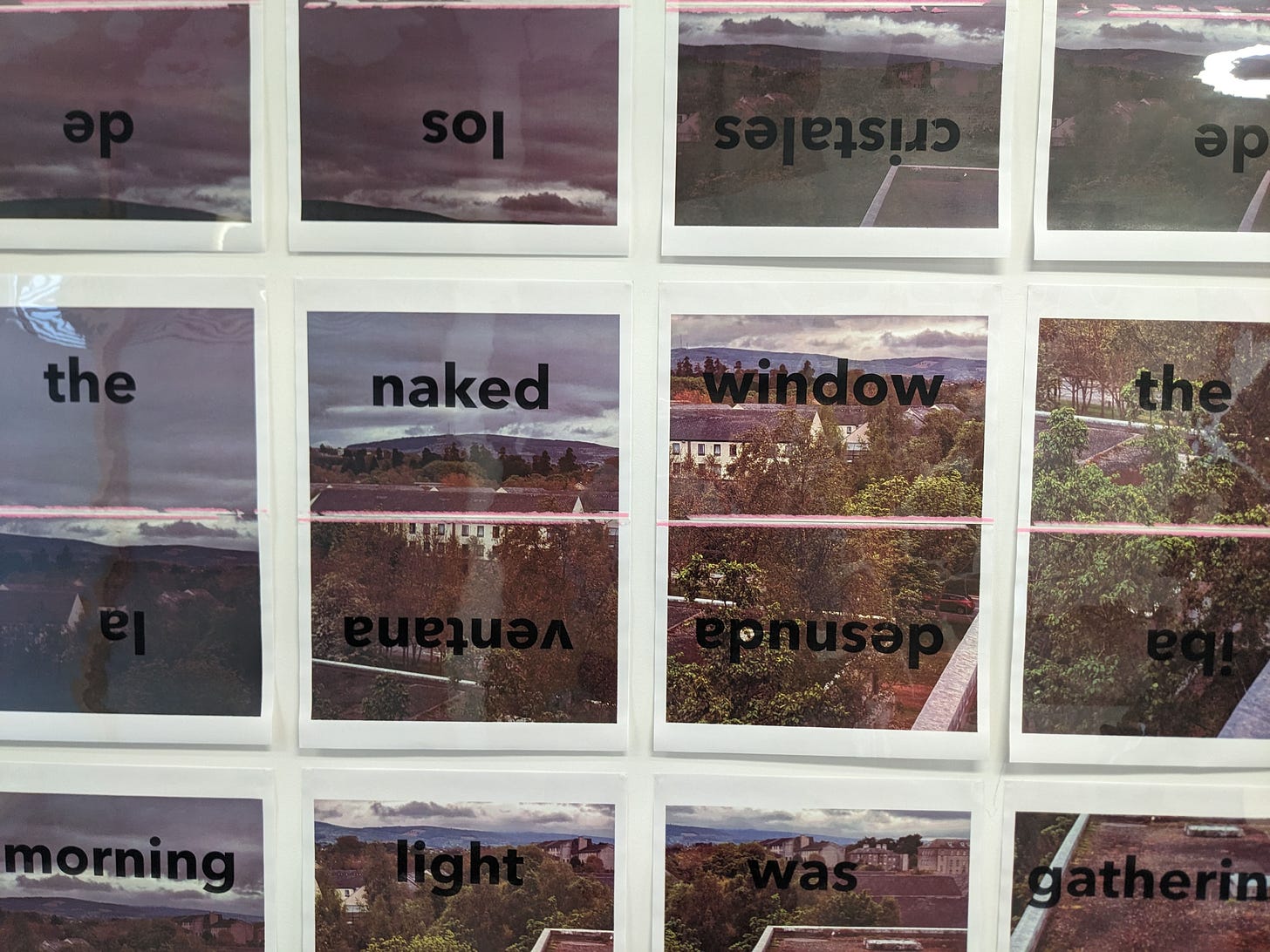

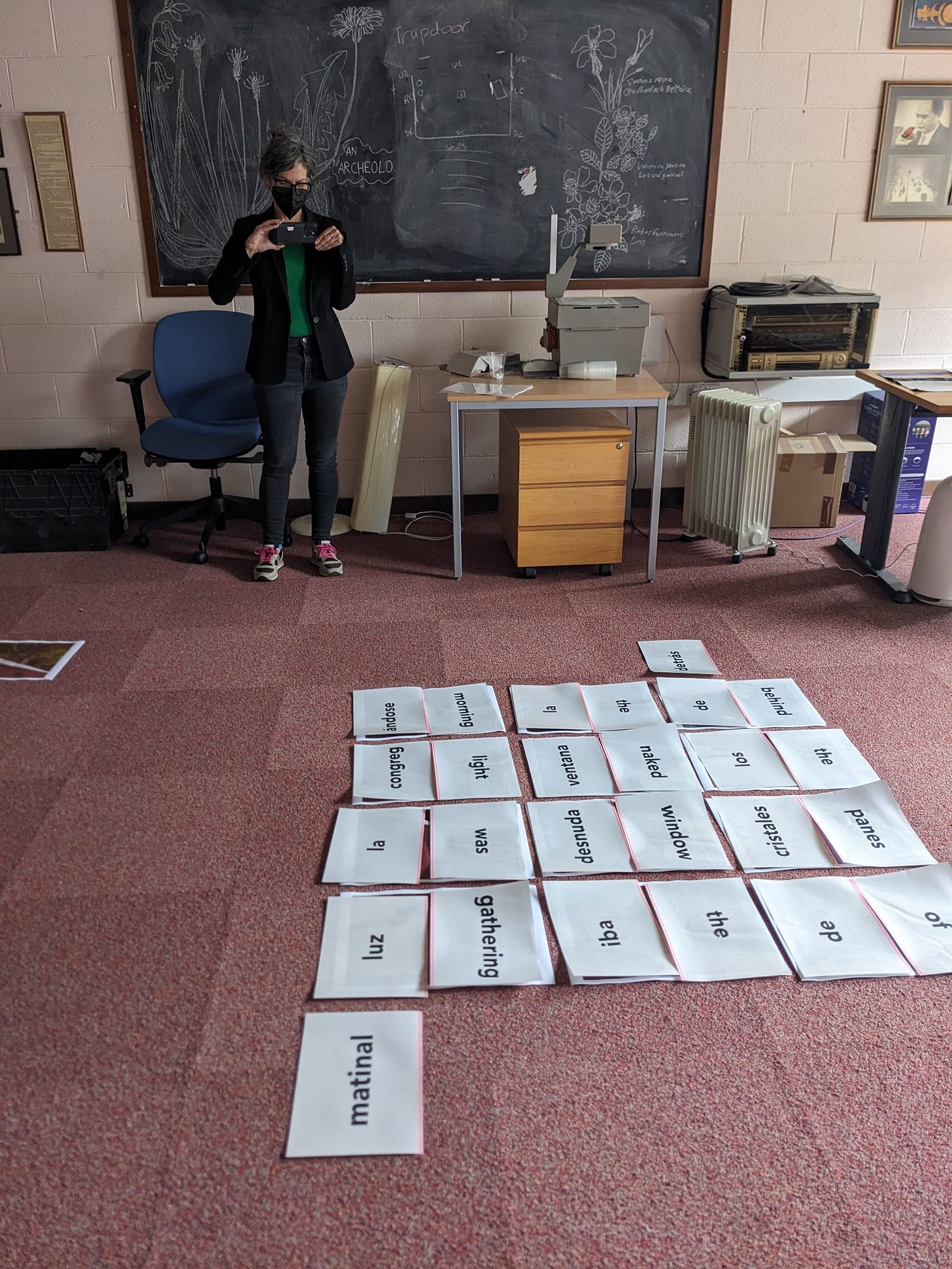

Behind the panes of the naked window the morning light was gathering / Detrás de los cristales de la ventana desnuda iba congregańdose la luz matinal (2024)

Acetate, photographs, light, text, institutional constraints

Edition of two

(The text of this piece comes from James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the Spanish translation by Pablo Ingberg. Two identical pieces were made, one to be installed in Dublin, Ireland, and the other to be installed in Tucson, Arizona, US, the places where each of us lives. Behind the panes…/Detrás de los cristales… superimposes Joyce’s words and Ingberg’s translation over a view from the upper floor of a university building in Dublin where this piece was made. Here, text crosses the “border” of the image in a way that echoes other “borders” crossed in this collaboration: institutional, international, linguistic, modal [digital/analogue], formal.)

We didn’t do this alone. From 2020-2022 we were part of a collective of artists and writers who met online to talk about artmaking and writing and helped one another keep our studio practices alive during the early part of the pandemic. Our conversations came from there but didn’t begin there—they began a few years earlier, via social media, where friends of friends connected us to one another. And even our work together on these two in-person improvisations wasn’t possible with just us: Chloe Brenan, an artist and a teacher in Dublin, did the bulk of the institutional work to invite Nicole to come to Dublin to give a workshop, deliver a talk, and install new work. And we worked in the shadow of so many other artists who have in turn felt the shadow of Joyce on them: we worked with Joyce and with his translator Ingberg at the distance of print media and time. We were assisted by the hands of the photocopier technicians whose work we had not seen but we could sense, not to mention those people who had taught us decades before to see the clear acetate of the overhead projector’s transparencies, and those whose labor produced the materials and equipment we used.

And we were prepared: we had been improvising with students and peers for a long time. We had been making art in the cracks around the demands of our day jobs. We had been working quickly, on borrowed time in between institutions or on weekends. We had been working outside of prestigious institutions, or working on their margins. We had been borrowing JSTOR logins and making photocopies after hours. We had read Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey, who write that “it cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment. In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can. To abuse its hospitality, to spite its mission, to join its refugee colony, its gypsy encampment, to be in but not of—this is the path of the subversive intellectual in the modern university” (“The University and the Undercommons”). We had been making art despite living in cultures and economies that say what’s the point as well as not for you. We had been practicing seeing our surroundings as already full of the materials of art so that we did not have to overcome a sense of “being without the correct materials” or a sense that “art is only made with art supplies”. We had built up a lot of flexibility, a lot of resilience, a lot of just-start, a lot of let’s-find-out, a lot of what-happens-if, a lot of saying-yes-to-whatever-happens. We weren’t put off by distinctions between high and low materials, high and low processes, or high and low ways of installing work. We were like gymnasts who, having practiced since childhood, can completely trust their hands and arms, feet and legs to catch them: and so barrel forward toward the spring, which appears to come from nowhere.

So when we walked into a room one Saturday in early May and said to ourselves, let’s make something, we were neither alone, nor were we beginning from zero.

We worked very steadily for about eight hours, with no plan in advance except to use some part of Joyce’s Portrait and Ingberg’s translation as the basis for our collaboration. We began by making things that were “not going to be the work”—an animation on the photocopier—and then we realized that the images there recalled the “roselight” of the passage we had chosen. What material could make marks on the dark surface of the prints? Oh: chalk. A piece was readily available. We tested it: yes, it will write on the toner. Capital letters? Cursive letters? We made decisions rapidly and assuredly, without thinking too much. Let’s see what happens. We passed the pages from one hand to the next, transcribing Joyce in English (me) and Ingberg’s Spanish translation (Nicole). The decision to invert the pages for the translation and to allow the “lag” happened in a split second. Shall we? Yes, let’s. The acetate with its second animation came much later, after we had tried out the acetates over the large photographs. Again, shall we? and yes, let’s. Using “low” materials—photocopiers, printer paper—freed us to play. Nothing is beneath notice and nothing is beneath us as material. If an idea didn’t work, we would try it a different way: move things around, change plans, cut, copy, paste. We could say yes to whatever happened, because it was all unforeseen and the stakes felt low. Something would happen. That was for sure. And it did. We did it together.

Art is play and practice. Housemaking is play and practice. Literature is play and practice. Relation is play and practice. All of this is attentive, demanding play built on lifetimes of practice. And the practice isn’t just art school, though if you happen to have gone that’s a special kind of intensive practice in certain areas. The practice is life itself: it’s walking while looking around, feeling the rhythm of your gait and noticing the world around you. It’s improvising in the kitchen with the last of the groceries. It’s having siblings and parents who want different things than you do, and finding ways to live together. It’s your secret play in childhood where a few ordinary objects became magical. It’s the human work of imaginative extension toward one another and toward the world. What artists do in practice is take the imagination we are all endowed with, and bring it into relation with the histories of forms (narrative, visual, conceptual, poetic, social…) and formal meanings, with the conventions and histories of usage, and with other patterns of meaning that establish the fields in which we think. But it’s not so different than what we all do in practice, every day.

Start where we are. Work with what we have. Not least of all one another.

Essays from 2023-24 are beginning to disappear from this space. Some will appear in Abundant Number, a series of booklets full of slow things. Abundant Number will have a first issue this summer. In AN.1, you will find a couple of walks from me as well as an album review by Matthew Houston, chapters from a novel by Steve Himmer, and a few other pieces of writing TBD.

Inside the first volume of Abundant Number, there will be a postcard that is also a text message. You can send it to a friend, a very delayed SMS. You’ll just need a stamp. Images and text by Andrea Blancas Beltran.

If you’d like to be notified when you can get ahold of a copy of Abundant Number or about subscribing, you can put some information here.

More news and more to read here in late June. I hope you’re well. I hope you’re safe and happy, that you’re free and able to do what makes you more alive. I hope that the occupation of Palestine, and the ongoing genocide there, will end. I hope that people everywhere will have safety, and comfort, and companionship, and freedom from fear.

See you in a month. Thanks for reading!