To hold the act of thinking before it resolves into thought. To write plans in, write grocery lists in, count chores off in, diagram ideas in until the ideas finally take shape. To be a physical location for so much that would be hard to hold in mind alone. To remind my hand how to move. To make the act of beginning to write an everyday thing, done without ceremony or anxiety. To convince me that writing is ongoing, as thinking is, without end, without scarcity, and without a target in mind. To practice in. To merge the acts of “write” and “draw”. To keep my brain lively while I wait. A place to make my whole life, and then, more or less, to leave behind.

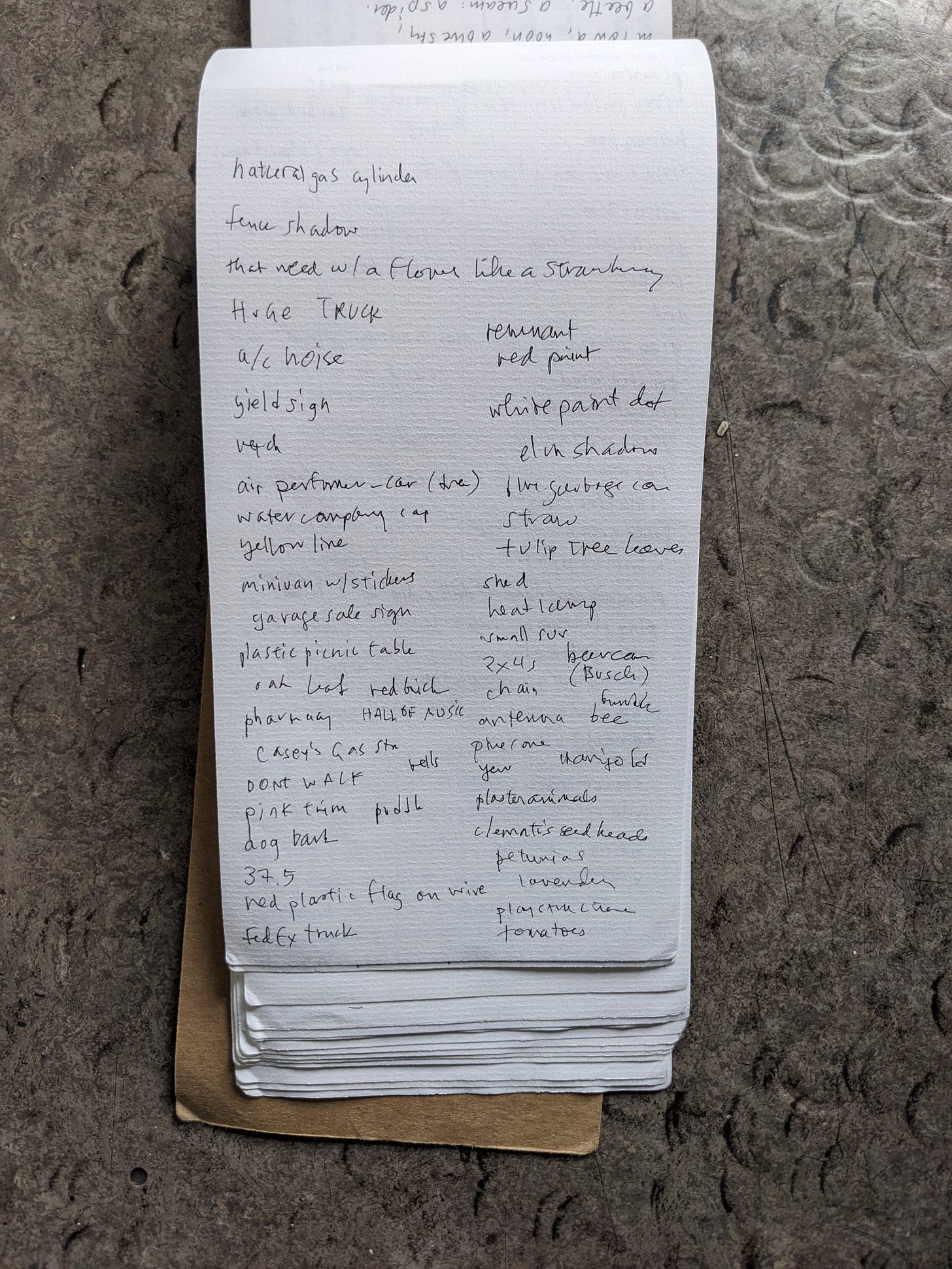

An example of a frequent exercise, twenty minutes of noticing exactly what’s around me in a limited area, usually about a square yard. I adapted this from a thick description exercise I learned from a sociology textbook, and over time it became a repetitive training in attention. Slow down.

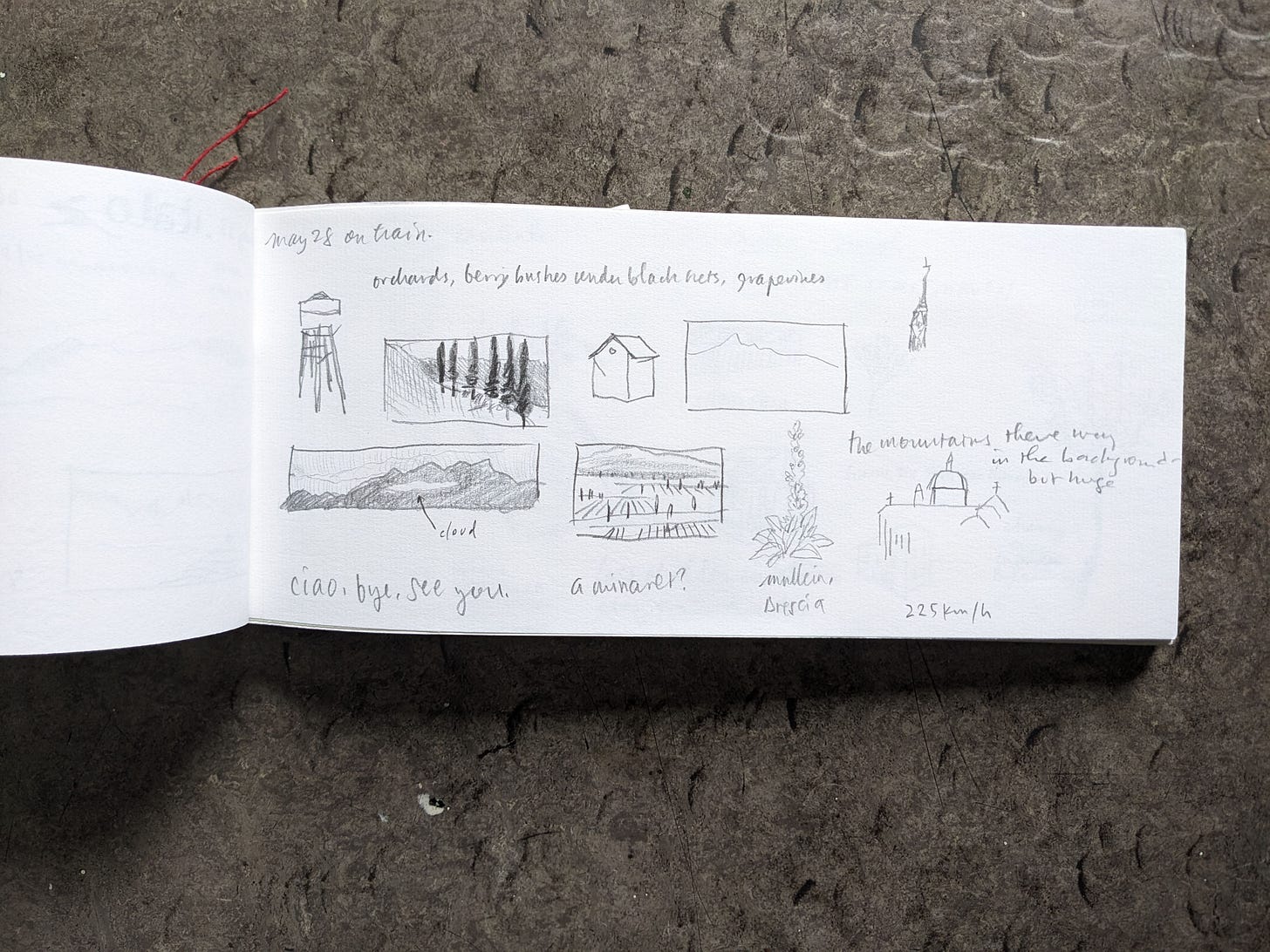

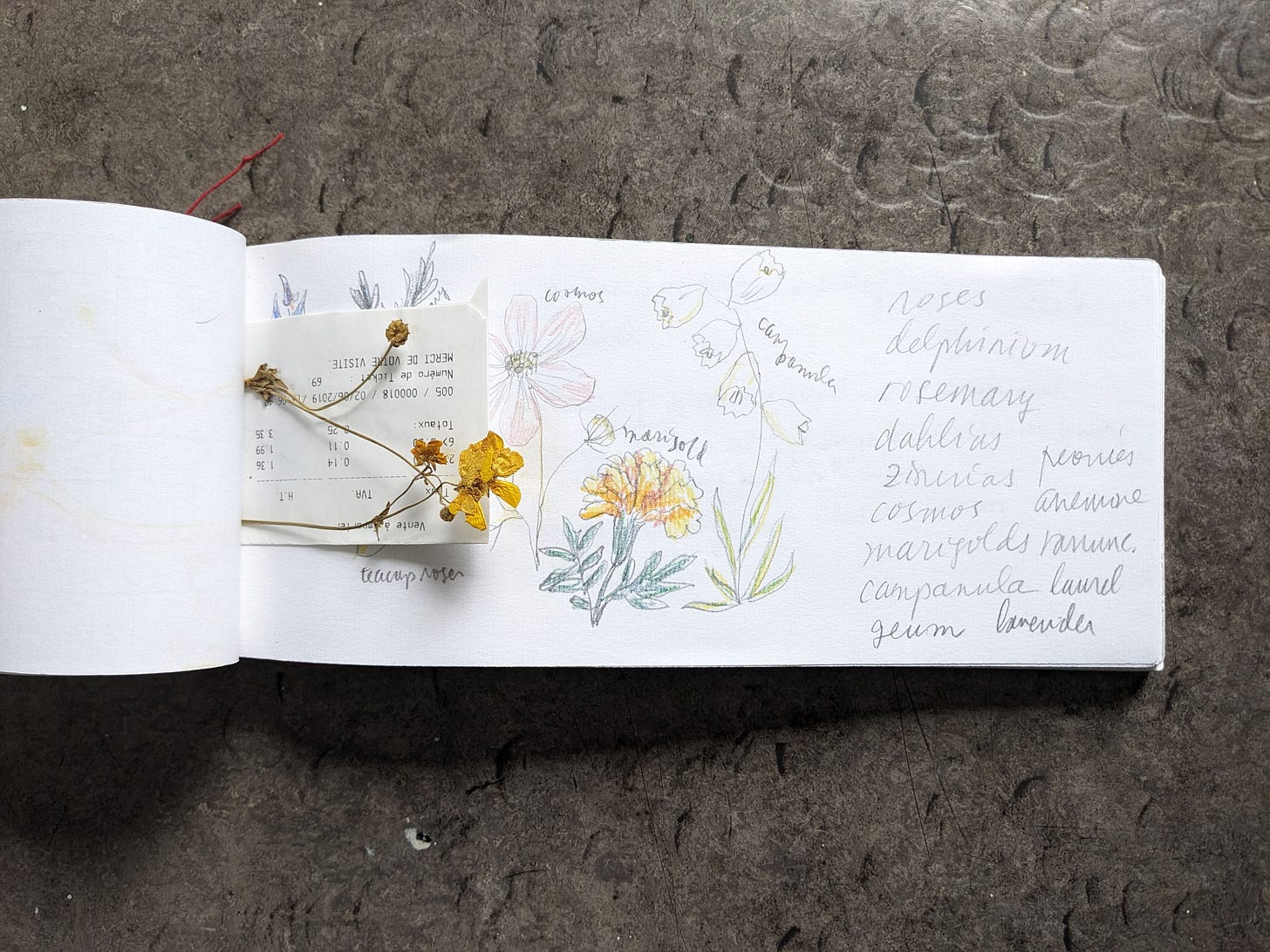

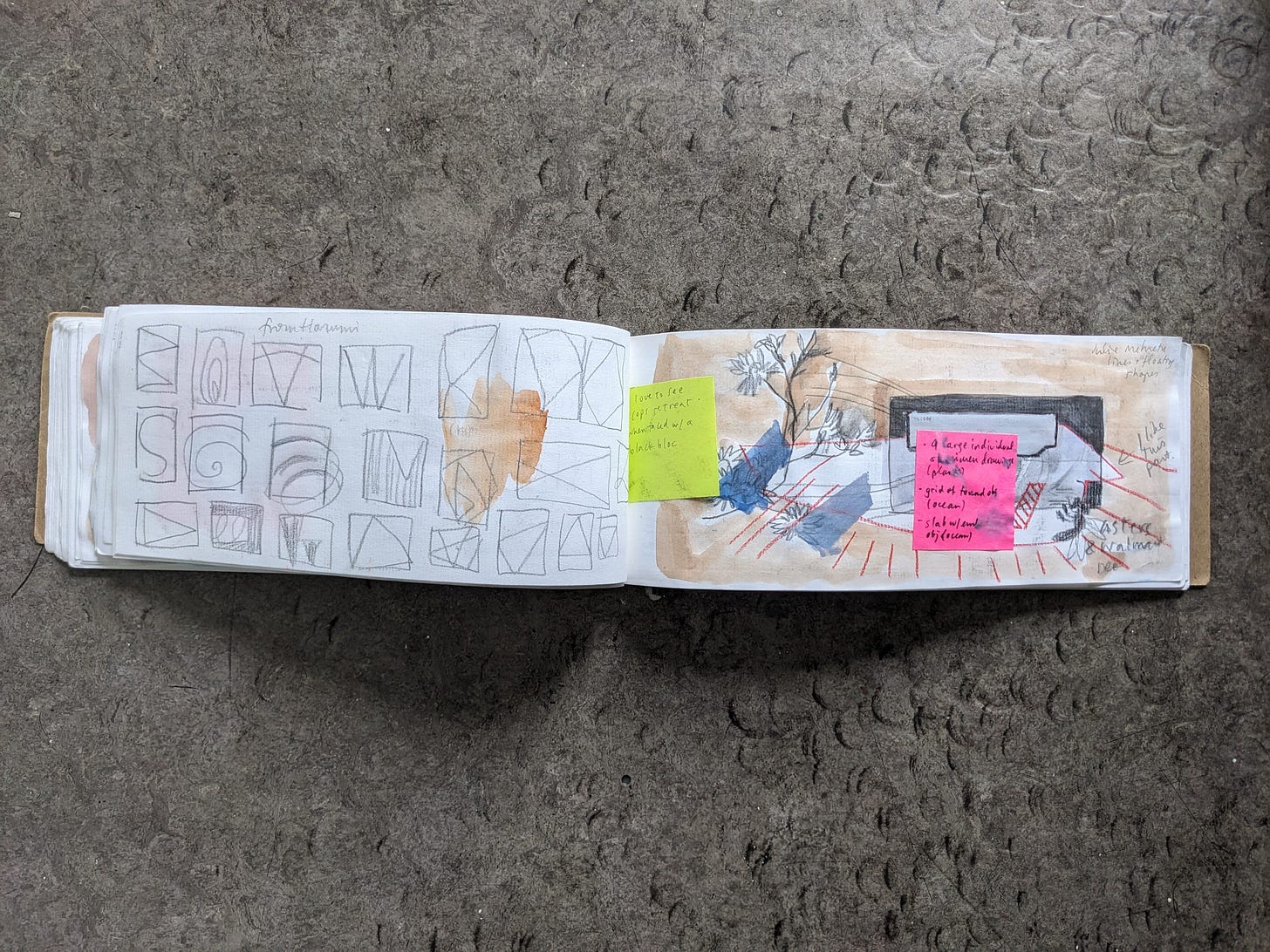

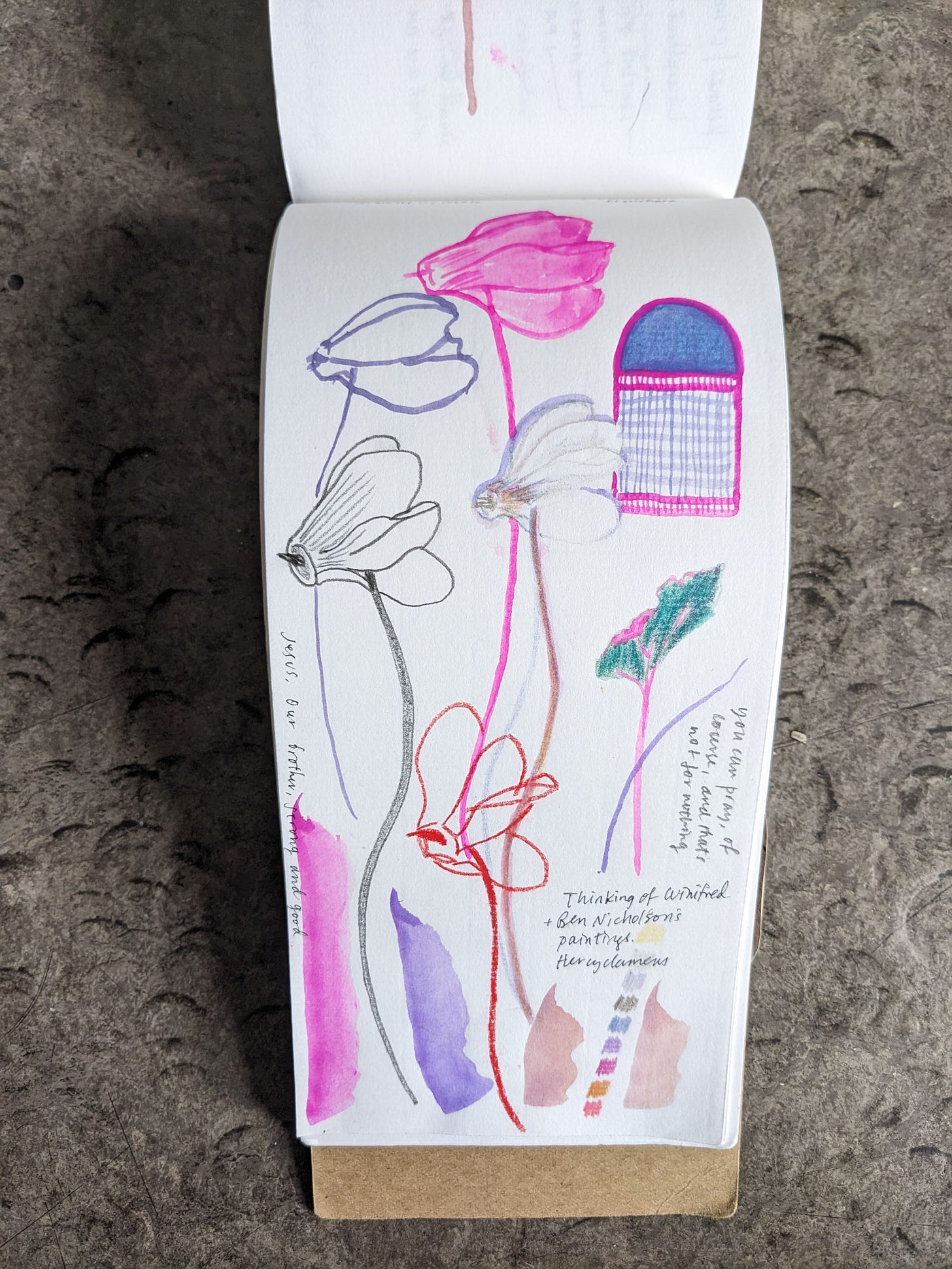

Vertical shape or horizontal shape, the page lends itself to different kinds of movement with the hand, which in turn render ways and kinds of thinking that are not at all the equivalent of the thinking I do in the orderly left-to-right, top-down of the computer screen.

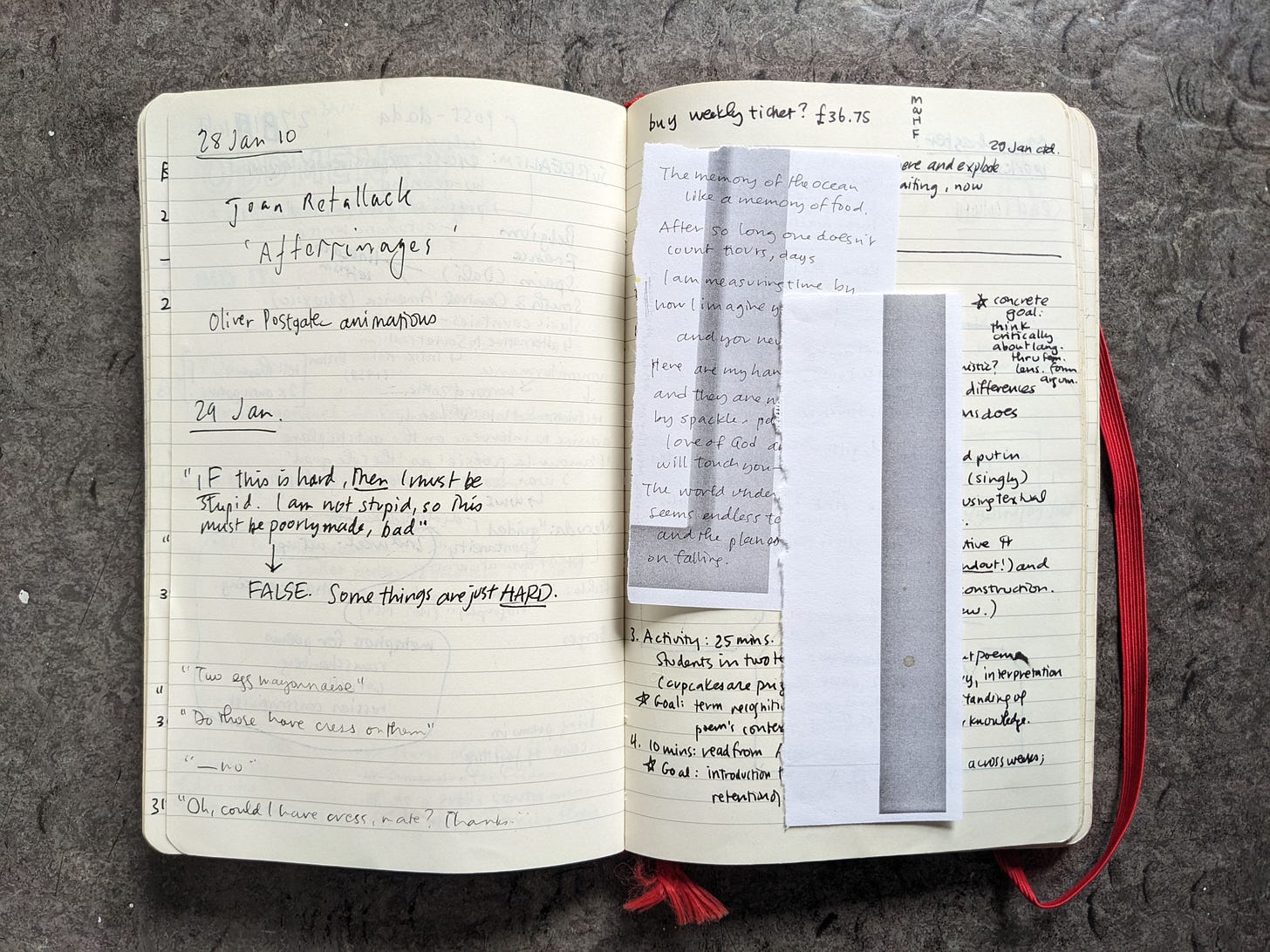

For a long time I used only red hardbound notebooks of that famous brand, with or without lines. Less superstitious now, I use basically any kind of notebook, but I do go through periods of one kind or another.

When I had easy access to a drill I made the notebooks above, half of a US letter-sized sheet (cut the long way), about fifty or seventy half-sheets in total. Cardboard from mailing envelopes (chipboard, not corrugated) and heavy, waxed binding thread (the link is to a shop I’ve ordered supplies from before—good quality). I used this way of binding; here is a print tutorial if you prefer. Once you have made a few books you start to realize what you want from them and you can make your own adjustments. For me this meant tripling or quadrupling the thread for a stronger binding, adjusting the depth of the stitches, and scoring or creasing the cover with my bone folder so it would open flat.

The long and wide form changes the way sentences can be shaped. When I am writing by hand, the material insists back at me. It makes me do things (like break a line, but not only) and it does things to me (like suggest relations across space and time). Of course, a computer screen is insisting, too; that shows up in how the shape of the A4/letter page is taken for granted by so many writers and thinkers. It’s just that, reading and working so much in that form, I often forget that it is not default at all but a design choice that I, too, can choose (or not).

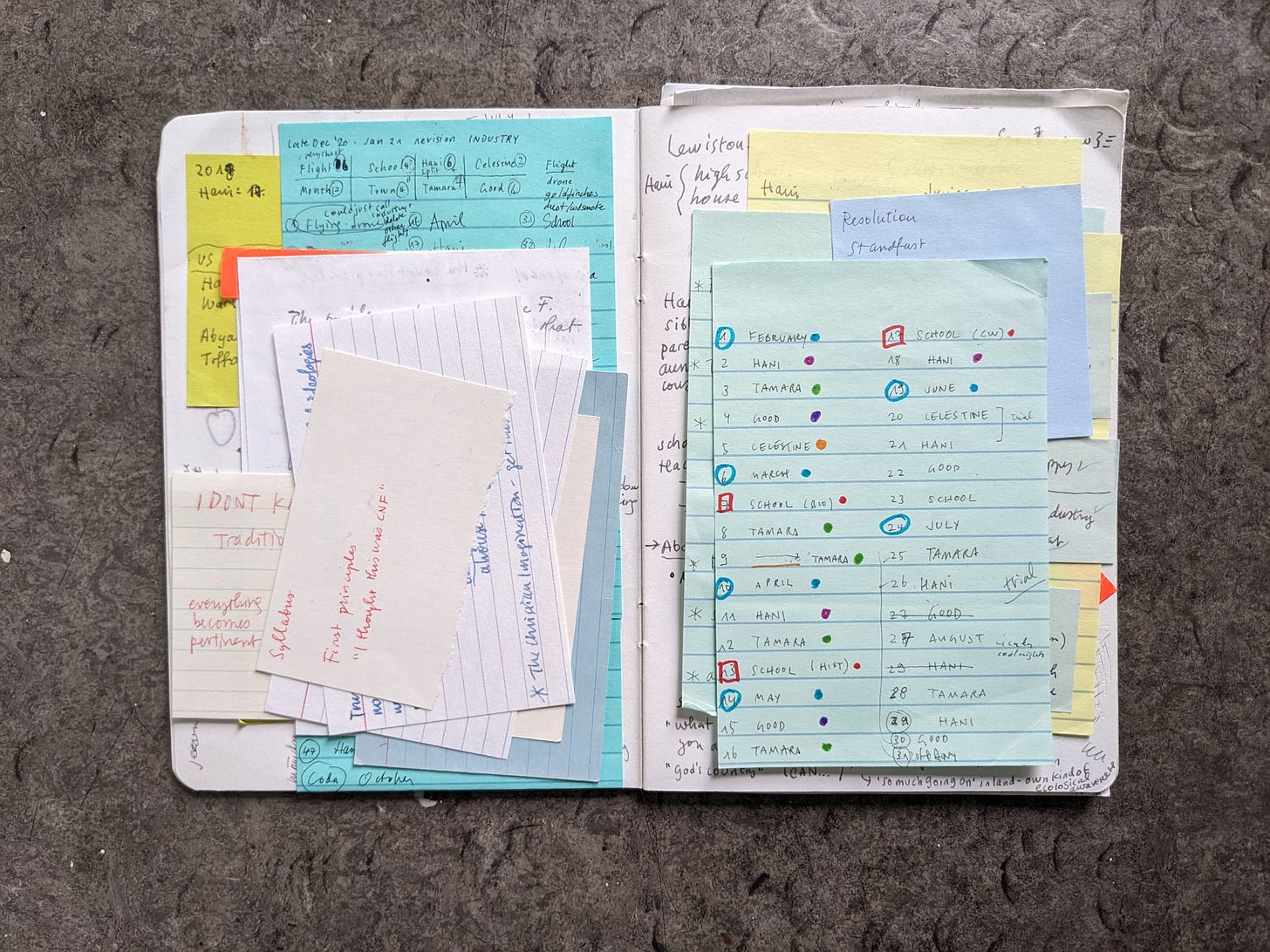

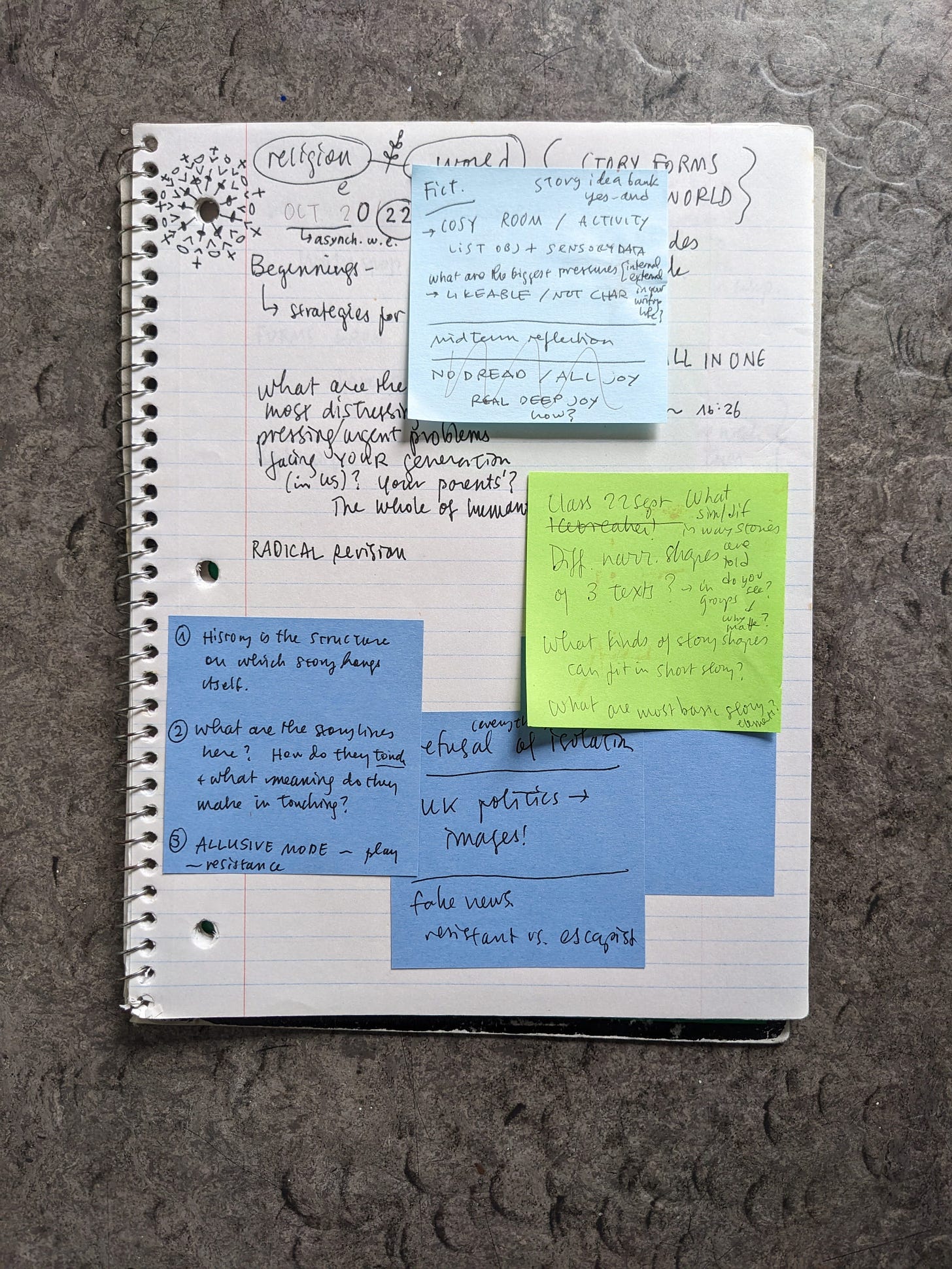

There is no perfect system; the imperfectability of it is the system. That’s life. You go on through it, trying to make sense of what’s in front of you, and trying to connect that to some other things. So here you see notes from a conversation or lecture about poetry (someone telling me about Joan Retallack) and me working out an argument with myself about my own tendency toward skepticism when faced with something that challenges me (“Some things are just HARD”) and a recording of a conversation in a café (I assume: “Two egg mayonnaise [sandwiches]” “Do those have cress on them” “—no” “Oh, could I have cress, mate. Thanks”). A question to myself about household finances: “Buy weekly ticket? £36.75”—this tells me I must have been teaching in Leicester at this point, and taking the train there to do some printing as well; for several years I was a member of a community printshop, which I loved. Scraps of paper tucked between the pages, just as they were when I opened this at random. And underneath, a lesson plan. Some people have notebooks for one project at a time but I have always ended up putting everything together in one place, like, well, my life.

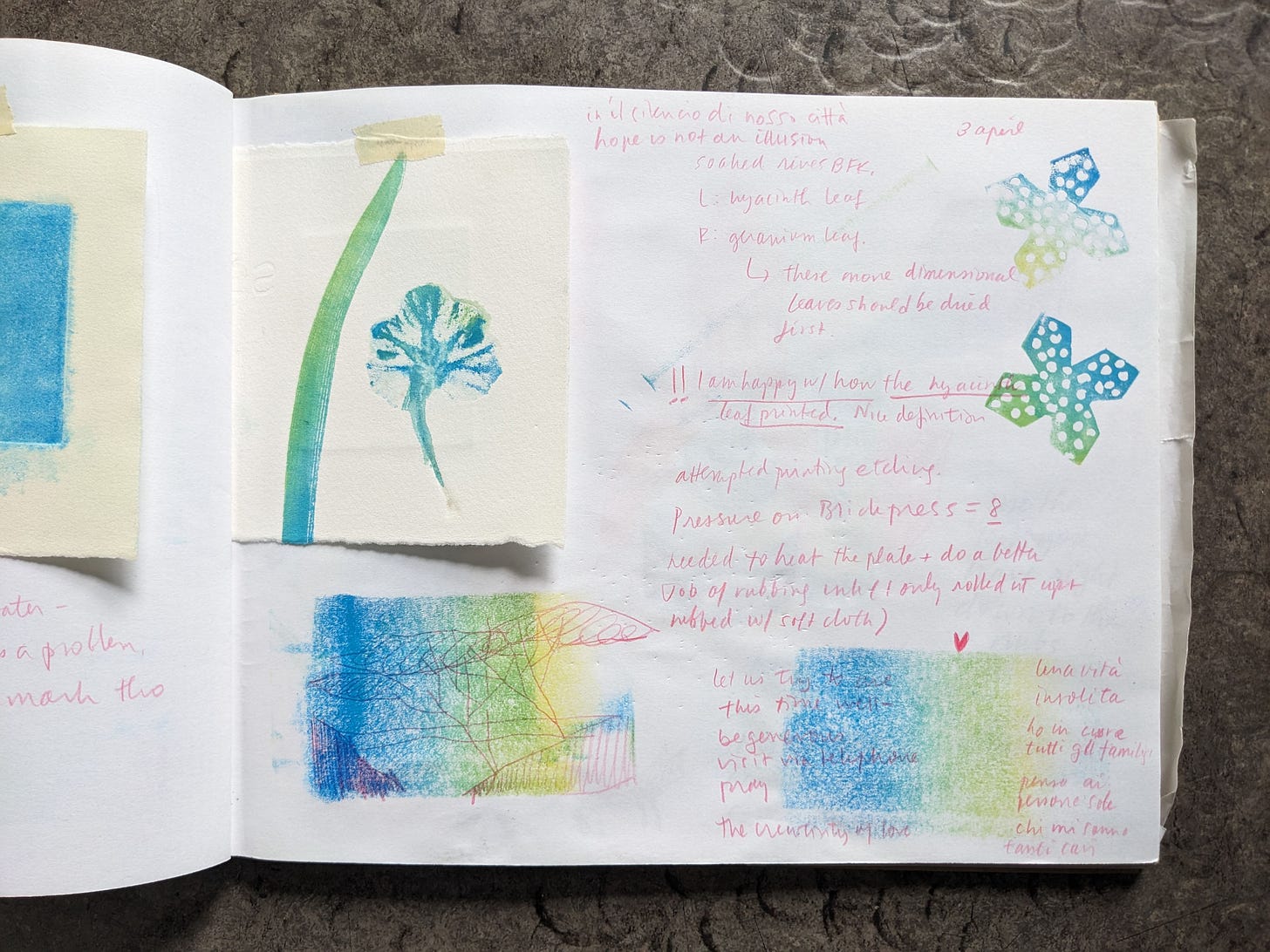

At the start of the covid-19 pandemic I was able to borrow a small etching press and I used some of my time making prints. I made some reduction linocuts and I also made prints by inking up plants I found on my walks and running them through the press. This page is me making notes about that process as well as about that time—back when so much was unknown: “Let us try to use this time well—be generous”. And there are some notes in Italian that I have no memory of writing. Looking at this page, I can remember both how free and spacious the days felt and how full of worry they were: for my students, who were often lonely and afraid, some of whom had no money; for ourselves, as we, too were lonely and sometimes afraid; for the future, which seemed more intensely unknown than it had a few months before. I also see this page with the eyes that time gives: I can see interest in the drawing I made over a rollout of ink on the bottom left. I see thinking I’m doing now about education and artmaking and community also present in my notes. I’m reassured: thinking and being is like water underground, there even when you can’t see it. Just keep making marks on the pages. Meaning will take care of itself over time.

I have always drawn while in class, and this one—a philosophy class I audited a few years back—was no exception. No reason that thinking has to take the form of verbal language. And memory too. The drawings bring me directly back to the formica tables in that classroom, and so much I learned there.

As a teacher, I have to remember that learning is not shaped like “objectives” and trajectories. It goes in all kinds of ways I can’t predict, and looks like things including the opposite of my intentions. My drawings must have irritated some of my teachers. I know they irritated my favorite high school teacher, a Christian Brother I revered, who taught religious history, ethics, and theology, and who slapped a book on my desk once and told me to pay attention. But drawing is often how I pay attention. Making notes does not need to be orderly or direct.

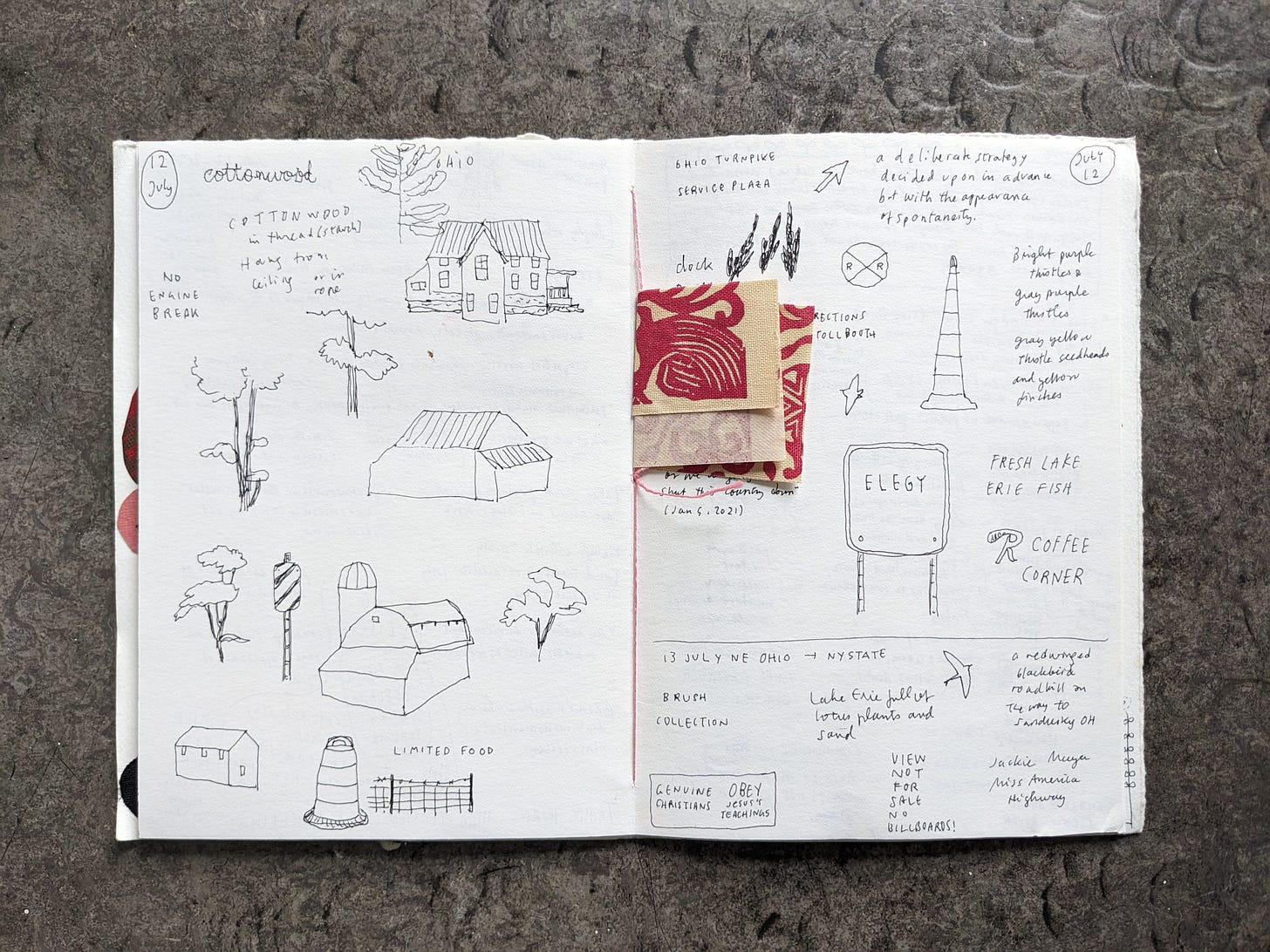

When reading was hard and writing felt impossible over the past few years, I began to make books like this one for myself: a cover containing four folded sheets. Sixteen pages. I made the covers out of Rives BFK 230 gram and the inners out of printer paper. Sometimes I would buy nicer inner paper. They are a little smaller than half a US-letter-sized sheet, a really enjoyable format. And such a small book feels like no pressure at all. This notebook records part of a long drive across the US in summer 2022. The language comes directly from signs I would have seen (with the exception, perhaps, of the phrases at top right). As elsewhere, this is me practicing seeing and recording.

Will I go back to these drawings and notes, “make something of them”? On the one hand, no; they are already the “something” they are. I feel obstinately that the purpose of the notebook is itself. It is not there to serve the “real” work of a book or painting; it is there as itself and for itself. On the other hand, to open an old notebook reimmerses me in the time and place of its making. Sometimes I am reminded of things I would rather not be—of my own past pettiness or smallness of imagination, narrowness, unformednes, and that helps me think again about how I want to be, what matters, how to make art and write, how to teach. Sometimes I am given images or words. Sometimes the notebook teaches me about the work I’m making, not least that I’ve been making it for a long time (so keep on!).

The notebook holds and teaches, keeps me patient, lets me be as large as I am in aspiration and imagination; it lets me bound all over, be profligate. A free place. It was never for the now that I have ended up in, but the making of the notebook is what brought me here, all the same.

Thank you for reading. See you in a week.

The "like" button is not a strong enough endorsement of what you've shared here. I'm reminded of how much I contain-ignore-reject-submerge the impulses I feel when I open my own notebook. Your words remind me of the sensory pleasure I feel from the texture and weight of paper in my hand and under my pen. They remind me of how much I've thought about--but been intimidated by--playing with paper, printing and constructing and binding notebooks, being messy in the process. I'm deeply indebted to you for sharing this. It pulls me like an invitation. I'm curious to see how I answer it.