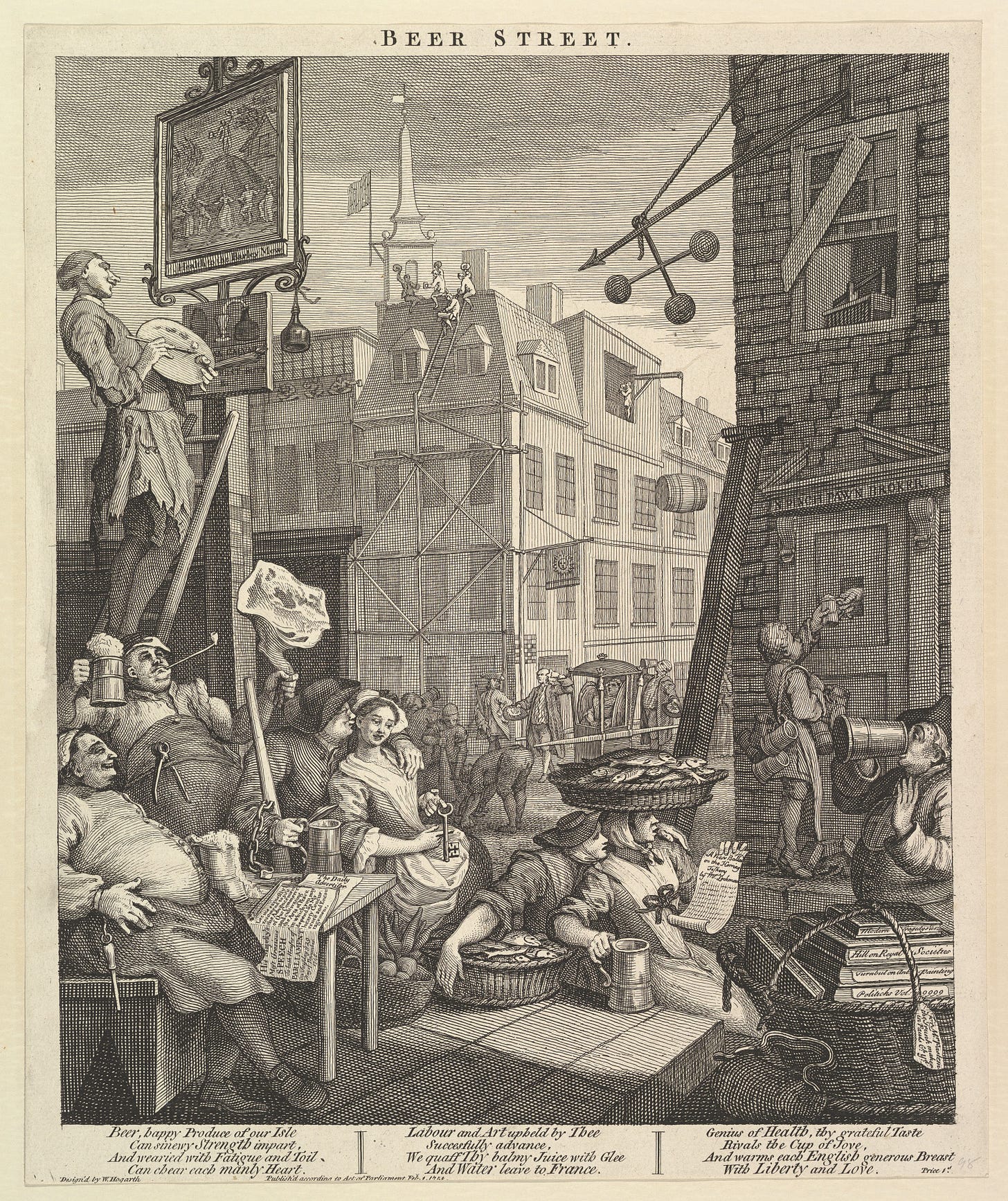

In 1503 a man in Nuremburg, Germany, made a watercolor of a patch of dirt and the ordinary plants growing there. This is The Great Piece of Turf and he was Albrecht Dürer, and the plants are still legible: great plantain, and dandelion, and burnet, and germander speedwell, and yarrow, and smooth meadow-grass, among others. Those plants can be found right there in the front yard or on the strip of median on a busy road. If you’re in the northern hemisphere, you’re probably within a dozen yards of one of them now.

![From the Wikipedia article on this image: "The watercolour shows a large piece of turf and little else. The various plants can be identified as cock's-foot, creeping bent, smooth meadow-grass, daisy, dandelion, germander speedwell, greater plantain, hound's-tongue and yarrow.[5] The painting shows a great level of realism in its portrayal of natural objects.[6] Some of the roots have been stripped of earth to be displayed clearly to the spectator. The depiction of roots is something that can also be found in other of Dürer's works, such as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513).[7] The vegetation comes to an end on the right side of the panel, while on the left it seems to continue on indefinitely. The background is left blank, and on the right can even be seen a clear line where the vegetation ends." From the Wikipedia article on this image: "The watercolour shows a large piece of turf and little else. The various plants can be identified as cock's-foot, creeping bent, smooth meadow-grass, daisy, dandelion, germander speedwell, greater plantain, hound's-tongue and yarrow.[5] The painting shows a great level of realism in its portrayal of natural objects.[6] Some of the roots have been stripped of earth to be displayed clearly to the spectator. The depiction of roots is something that can also be found in other of Dürer's works, such as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513).[7] The vegetation comes to an end on the right side of the panel, while on the left it seems to continue on indefinitely. The background is left blank, and on the right can even be seen a clear line where the vegetation ends."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff087fefc-7892-4dce-a427-a8cb0d5889e8_1024x1315.jpeg)

I can’t remember when I first came across this image of weeds and dirt. It was probably around the same time as I was introduced to Dürer’s more famous engraving called Melencolia I, so somewhere between 2004 and 2006. I’m going to loop away from the weeds and the soil in the image above for a while, and I’ll come back to them at the end. But in order to think about The Great Piece of Turf, I find I have to think about this other image, too. And part of what I want to think about is the difference between how Melencolia I was made, and how The Great Piece of Turf was, which will take a little time. So onwards with this looping-out, and eventually we will loop back.

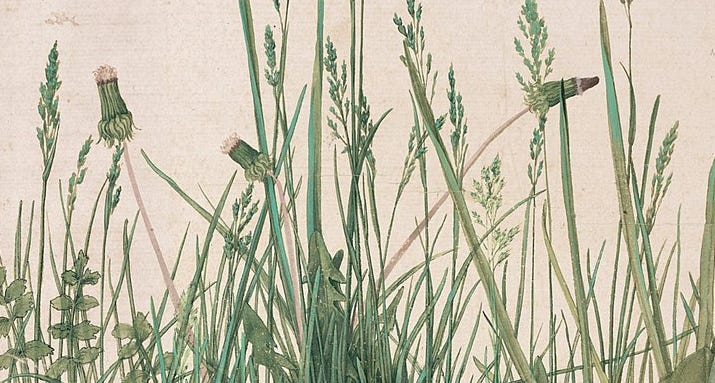

This engraving, in which a more-or-less human being (with wings and a wreath-crown and a grumpy? pensive? expression) is surrounded by a cherub, a sheep, tools, and objects of mysterious meaning and importance, is maybe better known than The Great Piece of Turf. The content of the image suggests its seriousness and importance. Knowledge and power, death and birth, religion and science. It’s allusive, referential. It’s coded—it lends itself to being read as a cipher—and it includes actual codes. Everything about the visual content of this image tells a story of in-group knowledge, exclusivity, control.

Engraving is skilled work. (The Met Museum has a great explanation, with brief video and lots of images, of how engraving works.) In Dürer’s time, it’s one of the ways images are disseminated widely: you can pull hundreds of prints using one plate. This is a revolutionary change in artmaking and also in communication in Europe, and it happens over the same period that books and education and literacy begin to change. Engravings travel. They are inherently multiple; the only ‘original’, the only thing the master-artist’s (or engraver’s, if a technician makes the plate from or after an existing drawing or painting) hand touches, is the copper plate. Made to move, and made to be seen in many situations, the engraving (the print in general) does not have the unique status of the painting.

This is something I love about prints—they refuse association with The Master (even if made by one, the hand that drew touched plate, not paper; often, prints were made by workers in studios rather than The Artist themself). Prints refuse singularity. They double and triple themselves and won’t play the game of pretending to be rare when they—when images, in fact—are not rare but shared, a human thing to make.

An economic consequence of the way prints are made is that they are generally less expensive than other kinds of art objects. I say generally, because I’m sure you could exceptions, but really I mean pretty uniformly. There are more prints than there are unique art objects like paintings; supply up, demand down, prices down. Even without money changing hands, the simple tendency of prints to proliferate (visit any printmaker’s studio to find out what I mean) means they don’t feel as precious. I can have one and you can, too.

Dürer made Melencolia I in a medium that allowed for mass reproduction, at a time when the mass reproduction of images and their distribution was still relatively new in Europe. This image could travel. It brought its strangeness and mystery with it into every room it entered. Its symbols were distributed, no longer closed away in only a few rooms. And now it is here, in your phone or on your laptop, between your hands. Mystery, strangeness—qualities of precious things. But the printed image brings these things out of solitude and offers them to many viewers. They are no longer reserved but shared.

Now I can begin to loop back again, to that watercolor painting of weeds and grasses. Those common plants we hold in common, painted about five hundred years ago and still conserved with care in the cool rooms of a museum.

I like to look at Melencolia I next to the watercolor picture of weeds and grasses. I like the difference between the moody, poetic, cryptic, occult subject of the engraving and the open, direct, immediate, familiar subject of the watercolor, and I like this especially because the difference in subject echoes a difference in medium, and a tension between image subject and the meaning in the media. Subject of Melencolia I: esoteric, lofty, coded. Medium: available, dispersed, mobile, multiple. Subject of The Great Piece of Turf: ordinary, familiar, proliferant. Medium: technically difficult, produces a unique work.

Both images are meaningful to me. Both are masterworks. Both are important in the history of European art. But there is a difference in what these two images do to me as a viewer: When I look at the watercolor of plants and ground, I don’t feel as if I’m looking through the picture toward “real” meaning, a hidden meaning that comes through symbolic or narrative meanings imbuing certain kinds of dress, certain objects. I feel like I’m looking at some plants, in part because I often do look at plants like these. I feel like I’m being asked to realize that I have seen these plants, and to realize that these plants are something that can be looked at.

In our time, we see images of all kinds reproduced and changed and moved and reproduced again. But this watercolor is an object that could not have been reproduced in Dürer's time (except by making an engraving after it: still not the object, but a representation of it). Even in our time, there is only one original, living in a museum in Vienna. I imagine it is behind glass, if on display, as drawings almost always are when in museums. The glass says precious. The character of painting—to make an image be singular—also says, in the language of the contemporary fine art economy, precious, though the insurance value of this work is not what matters to me. I don’t even think about that kind of precious when I look at this image.

There is only one of this image. It cannot reproduce itself. The original remains original. And yet it is not the image of a mysterious, extraordinary being surrounded by the tools of erudition and skill. It is an image of beings from our daily lives. So—precious what? The character of the medium discloses the dignity and importance and meaning of the subject: these ordinary plants are precious.

Precious weeds, precious grasses, precious dirt. Precious looking and precious record of having looked. Dürer’s Great Piece of Turf is one of my favorite pictures in the world, because it looks so carefully at something so ordinary. This picture reminds me that very little separates artists' looking from ordinary looking: just time, attention, repetition, and care. And all of those, like plants, only require cultivation to come into flower. The sources of artmaking aren’t far away: they are right here. All we have to do is look, and look again, at what is nearby—often so nearby as to be invisible to us. Look again. And again.

In two weeks I’ll return to this image and think about it again. I’ll also record an exercise for writing-thinking-being that arises from this image. Thank you for reading—and being—here.

Éireann, I love this post SO much. I hadn't seen either of these works before, and I appreciate reading your thoughts and the comparisons you make. I have a love affair with the moments in everyday life, and weeds are such a huge part of that magic - to imagine someone so far away and so long ago experiencing and capturing that, and that you and I would be having a digital conversation about it after so much time has passed and still appreciating the same things? Wild. :)

"not rare but shared, a human thing to make." Love this very much (and the whole essay really).