[There are a lot of new people here, thanks to my friend Jon in great part, I think. If you want to know what this place is about, this will give you a sense of it. In brief, I am writing an essay each week for the twelve months between March 1, 2023 and March 1, 2024. They all go out on Sunday mornings Irish time. Each month, one essay is titled “[while walking]” and is drawn from my near-daily walks in the place I live, and another is titled “[while washing the dishes]” and is a chance for me to write about—or invite someone else to write about—something that’s entered the frame of my thinking while doing housework. Across all the essays here, I take Fanny Howe’s idea of “bewilderment” as a guiding principle both aesthetic and ethical, and consider Virginia Woolf’s “little arts” of “talk, dress, cookery” alongside other arts. I aim to think about what it might mean when Frank Bidart asserts that “being is making” and when Toni Cade Bambara writes that the role of the artist “is to make revolution irresistible”. Thanks for being here.]

A note about a few upcoming events in November and December.

On November 9 at 7 p.m. Irish time in the Classics Museum at UCD, Jeanne Tiehen will direct a staging of my work An Archaeology, for which I’m making costumes. In-person only; tickets are free but very limited. Email sasha.smith@ucd.ie to book.

On November 19 at 2 p.m. US Eastern I will give the first of two lectures as the Annulet Inaugural Linkages Lecturer. I will give a talk entitled “When you get someplace new, learn to read the landscape like an alphabet”. This talk will be broadcast online, for free. To register, please click here.

On November 21, along with two other writers to be confirmed, I will read and talk with the others as part of the Trinity College Literature & Resistance Series, in the Trinity Long Room Hub. Event and booking information will be here (in person only).

On December 10 at 2 p.m. US Eastern I will give the second of my Linkages Lectures. I will give a talk entitled “On the line”. This talk will be broadcast online, for free. To register, please click here.

There is a lot of beauty in this city, like everywhere. You look long enough and you can’t stop seeing it. People want to make their spaces feel right to them, and that yields beauty—not the Home & Garden variety, not the Instagram variety, which are a skin of “beauty” but not beauty. By beauty I mean, among other things, the old man I often greet while walking home: he sits on his chair inside his southwest-facing doorway anytime there is sun in the afternoon. He has built little shelves all up and down the inside of the frame to hold plant pots and has tiled them with orange and yellow and brown tiles. He did it himself, he must have. They are ugly but they are beautiful because they are particular—they show the making and the maker in them.

There is a lot of “good taste” here, too; a lot of self-conscious correctness, a lot of primness, a lot of what feels to me like Prufrock saying to himself, “Time to turn back and descend the stair, / With a bald spot in the middle of my hair — / (They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)”. A lot of what looks like “beauty” and “good taste” here, as elsewhere, is the adoption of the mores of wealth as a sign for beauty. These mores produce desire in me—they signify space, light, not having to move yet again, no landlord, some kinds of ease—but they often, ultimately, feel hollow. I often feel more alive in a room someone has decorated with “too many” patterns and colors than in a “tasteful” gray or white and pale wood room. I love this essay by Anne Enright in a similar vein. In the end, the facts of the world are generally more of a blur than a binary. The surprise of individual seeing and world-creating pokes through and ruptures the skin of “good taste” to make a moment of beauty.

In any case, let me be clear that when I say “beauty”, I’m not talking about “good taste”. I don’t care about “good taste”. “Good taste” is a set of rules that serve wealth and power by grinding in the values of of wealth and power to the point where they seem normal, unquestionably desirable, almost signs of health (aesthetic as well as bodily/mental), and nearly invisible. “Good taste” is a continual lesson in not-looking-at-the-world. “Good taste” is fitting oneself into a given container and god help you if you overflow. No, thank you. Not “good taste”; I’m talking about the beauty of invention and of lived-inness. The beauty of specificity of attention. The beauty of being-person with other people. That’s what we grieve when anyone dies, I think—the way they made a world, which no one else could have done in just that way. And then also the beauty of the world they were, taste be damned, which no one else will ever be, despite the preservation of matter and energy in other forms.

There is a lot of vileness in this city of beauty, too. Vileness and the pressure of “good taste” go hand in hand.

I peel far-right stickers off postboxes, garbage cans, lightpoles, and signs as I walk. They have visual rhythm: appearing every so often along particular stretches of road, in particular areas in my neighborhood. I have never seen anyone put them up, but they are there every week, sometimes more than once a week. And I rip them down every week, sometimes more than once a week. I imagine no one sees me doing that, either, at least most of the time; most of the time, people don’t look around them as they walk or drive. I know that it is not ‘becoming’ of me, a middle-aged woman, to stand and touch ‘dirty’ things in public spaces. Though I generally feel unseen while I peel the stickers off, when I am seen, I see people’s disgust. It is true that the sides of public trash cans are dirty and I, in my leather shoes and work clothes, am ‘clean’. The meniscus of manners and class and taste ought to keep me well-behaved. But I reach out and peel the sticker off and throw it away.

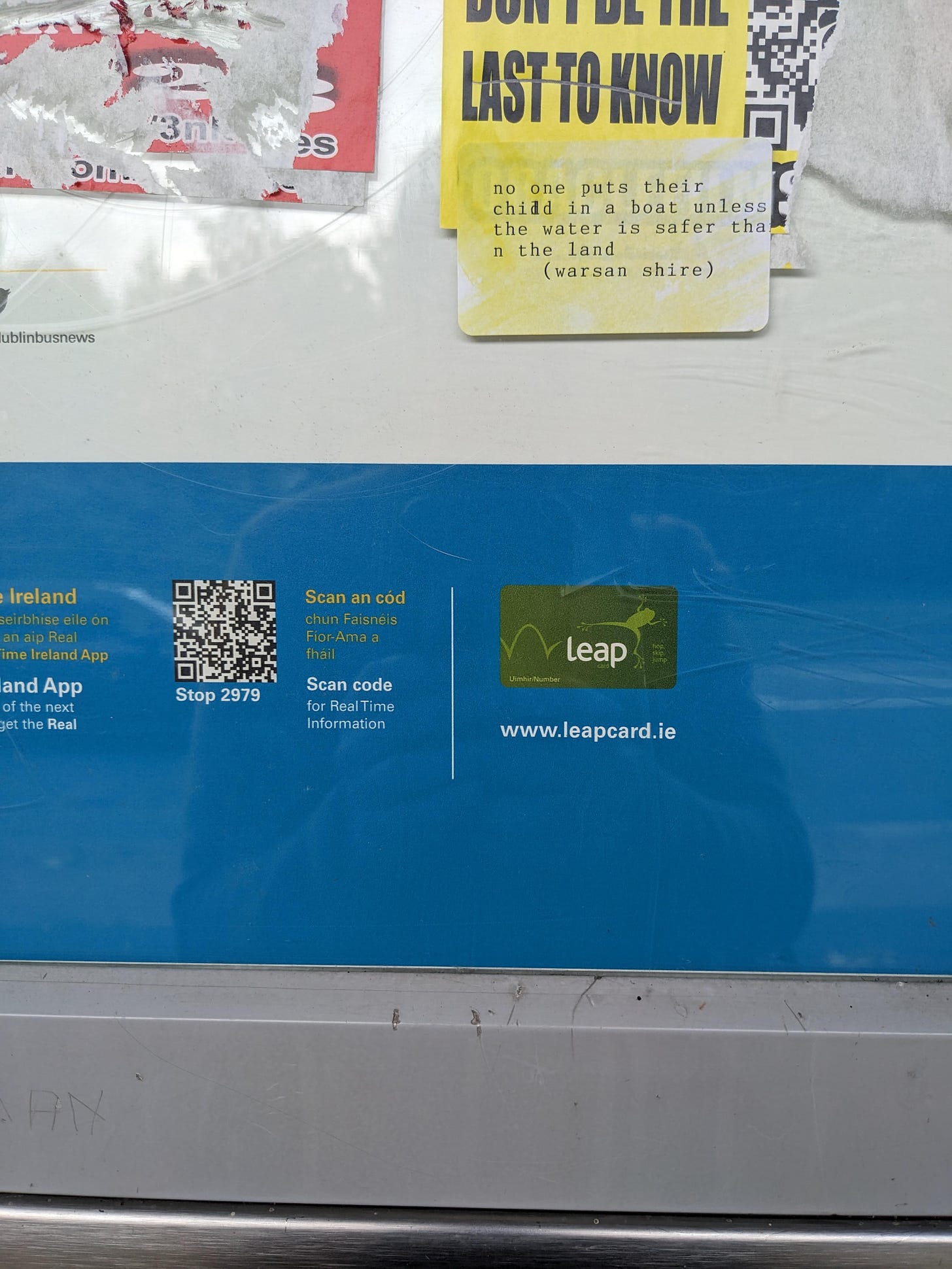

There are stickers that tell lies about vaccination; there are anti-trans stickers; there are antisemitic memes, both gross and grossly obvious; there are profoundly disgusting Islamophobic stickers that someone keeps putting up by the mosque; there are fascist recruitment stickers with QR codes; there are conspiracy theory stickers; there have been, recently, really vile stickers that use the likeness of George Floyd to stir up white supremacist fear and propagate the white supremacist ‘replacement’ myth. In the past few months I’ve seen large wheatpaste posters as above, that appear to be from the city council but are not, and that dehumanize and demonize drug users and homeless people. I’m reciting the stickers’ content categories not to reproduce their rhetoric but to lay out the the field of their concerns—the people they unpeople, and how—as well as the facts of their persistence, their prevalence. This is the underside of good taste, when good taste means looking away, refusing to name things as they are, the use of euphemism, comfort. When good taste means being able to opt out of confrontations with what dehumanizes us, or to feel that another person’s dehumanization might be ‘deserved’ or somehow have nothing to do with one.

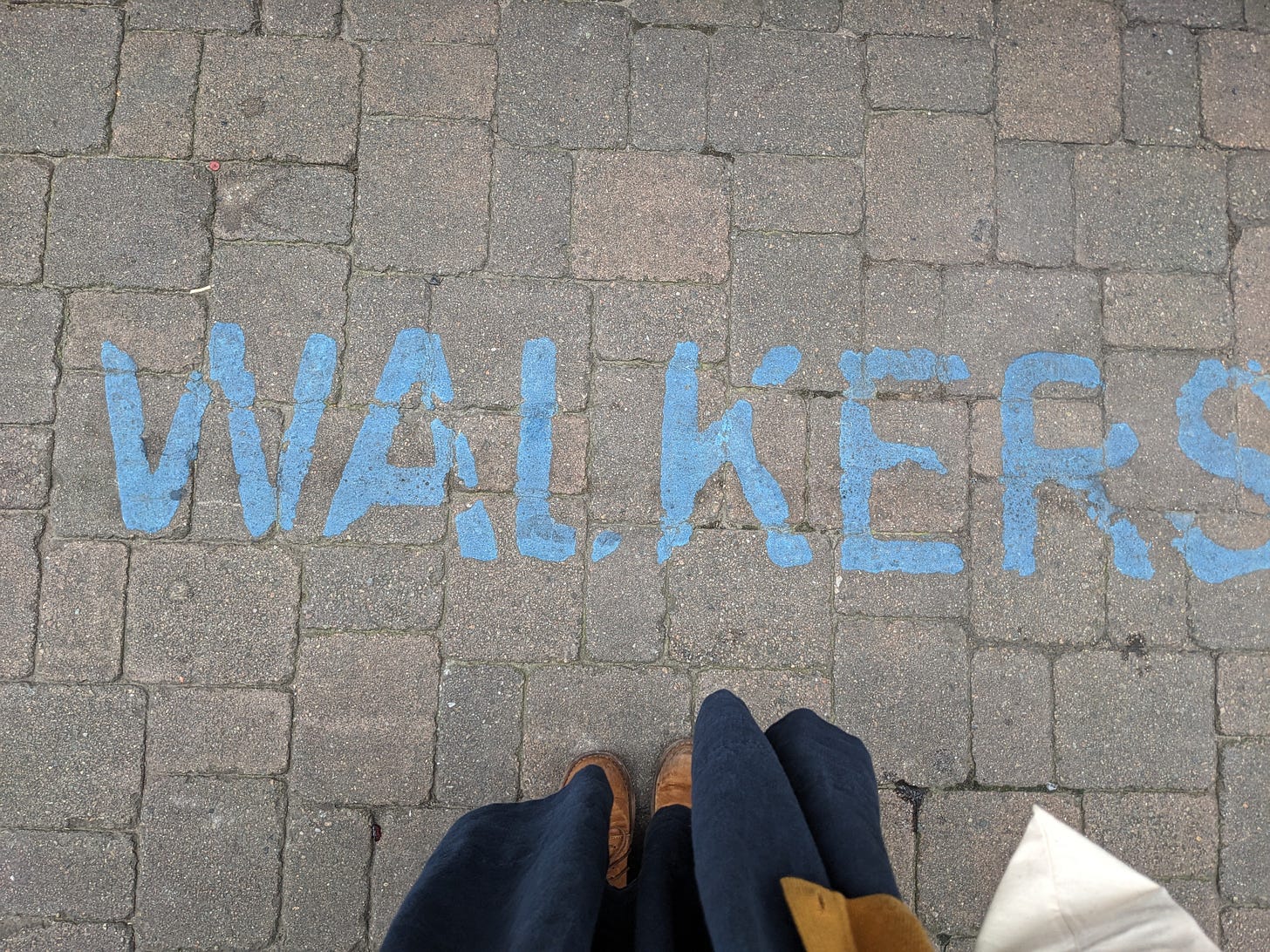

Often, walking, peeling off these stickers and throwing them away, I feel weighed down by the ugliness of this place, its dense and complex histories of violence woven through with the world-crossing violences of antiblackness, xenophobia, antisemitism, Islamophobia, much of which is exported by the place I’m from. I don’t know what else I can do in the face of this feeling of weight. There is no heroic action. There are only the everyday actions of looking, thinking, asking, refusing, insisting, examining. So I go on walking and peeling the stickers off, walking and peeling and throwing the stickers away. In this I am alongside others who also do this small, daily work. Writing NO and FALSE in big letters on the stickers we can’t tear off. Putting up our own stickers, too. The sticker calls the eye and says, here. One nice thing about my leather shoes and work clothes—the invisibility they lend me—is that I can put up stickers mostly without being seen. Any risk of being seen is diminished by the sensation of changing the world, materially, microscopically, toward what feels vital and alive rather than deathly. And the risk is also diminished by my smallness, my femininity, my whiteness, my work clothes—the signs of my belonging to an order of “good taste”, the signs of my “unthreateningness” and docility.

Sometimes the stickers have already been defaced or partially removed when I find them, which makes me feel like we are working together, me and whoever else is watching for them and tearing them down. We sticker-removers are termites of the fascists’ world, unmaking some transmitters of violence one tiny chomp at a time, over and over and over. It takes no special tools to be such a termite. Fingernails do most of the work. An ID card peels difficult ones off. And a soft-leaded pencil (its dark marks will not wash away in the rain) permits one to deface any part one can’t remove.

Living beauty is possible for all of us. We can do it—make minuscule changes to the world we move through that insist that care, justice, liberation, that compounding of acts that add up to beauty, are more important than good behavior. I think beauty is a disturbance in the field of comfort—the comfort often given the names of taste, or propriety, or manners—that confronts me with the irreplaceability of everything (everyone) living. I feel a demand to work and fight, mourn and build for and with others when I am faced with that.

Beauty forces a reckoning, over and over, on a minute scale, with my own complacency. It makes me see in specific, makes me see pattern and meaning, especially pattern and meaning that’s not my own. I think beauty confronts us with the eachness of each of us, our difference, our irreducible human preciousness, patterned together. Not conformity; finding out. Widening. The way a new parent looks at their baby and realizes, you are absolutely complete and I couldn’t even have imagined your you a month ago. You. Us. Here. Together. For one another. Clear-eyed. That’s what I mean by beauty.

Thanks for reading. See you in a week!

Thank you for this. Thank you.