August. Almost autumn. Hardly feels like “August” here in Dublin, but whatever I feel like “August” should be, this has been the August it is: more or less cool and more or less damp, after a July that was the rainiest July on record. Most days have been whitely overcast. There has been fine rain, heavier than mist but not heavy enough to drench. There are ripe figs on trees behind stone and brick walls, and blackberries reaching from behind white-painted metal fencing. Most days have had a period of fair weather in them.

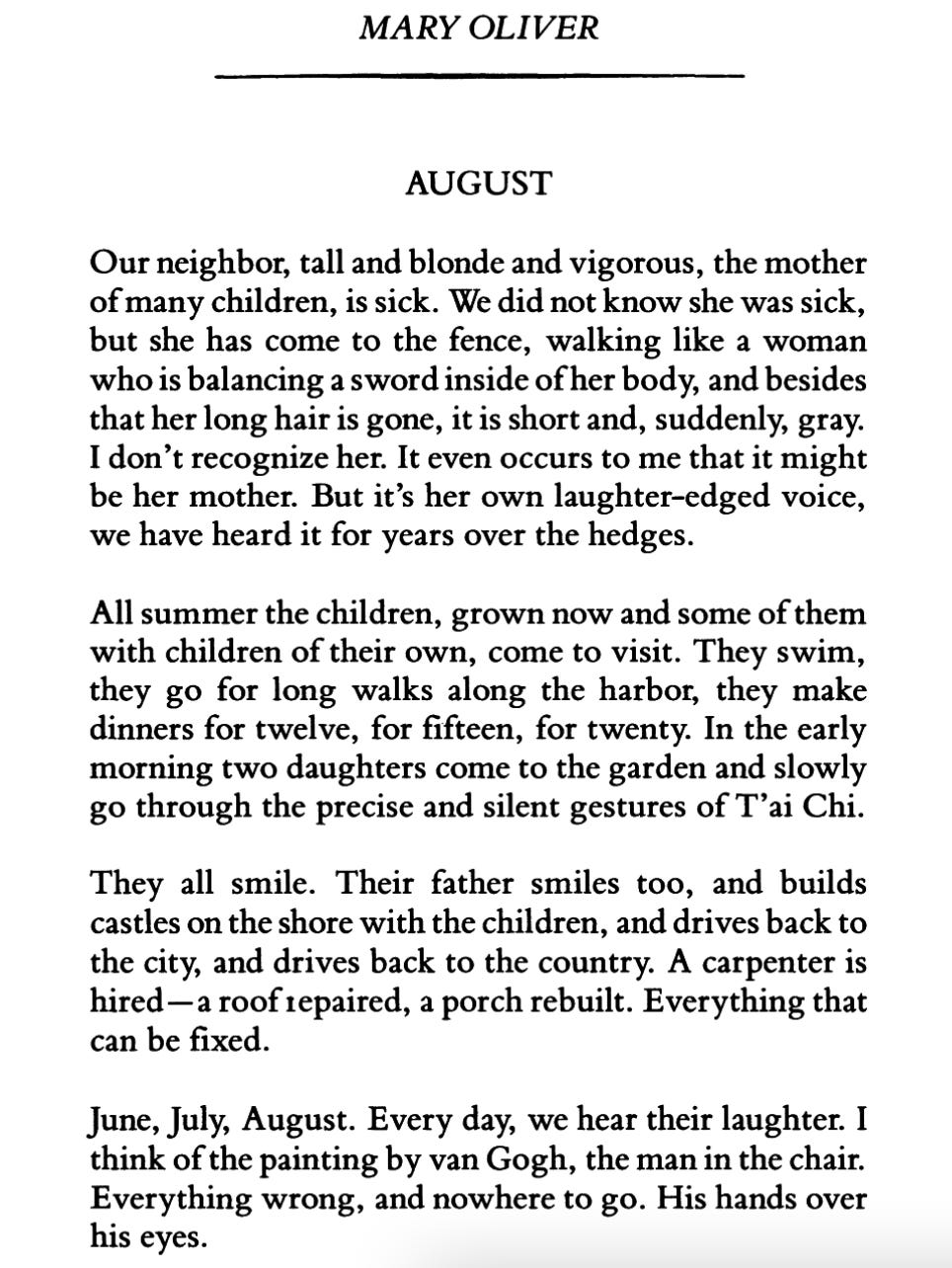

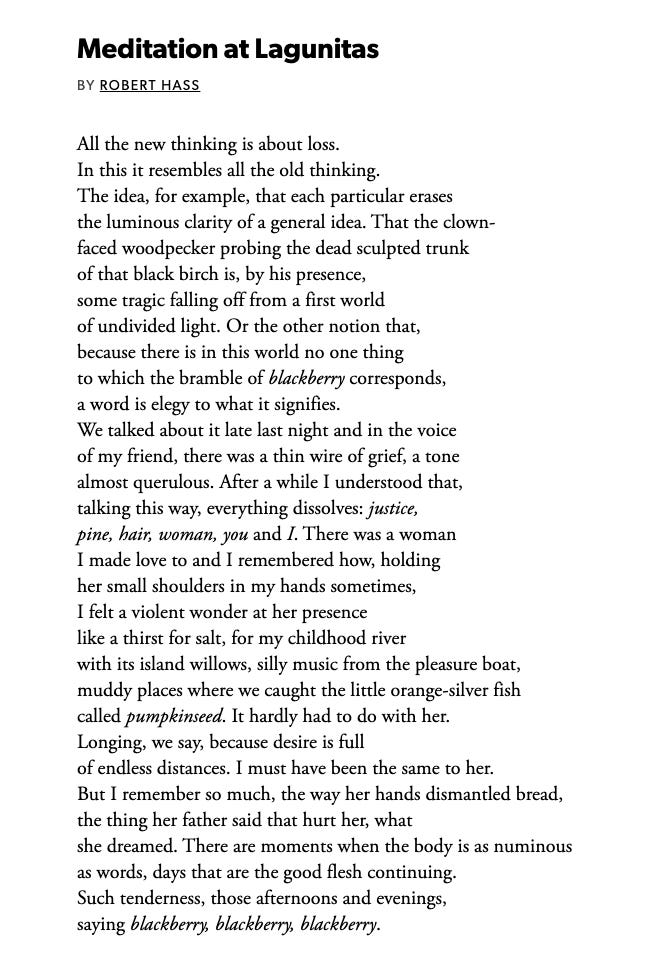

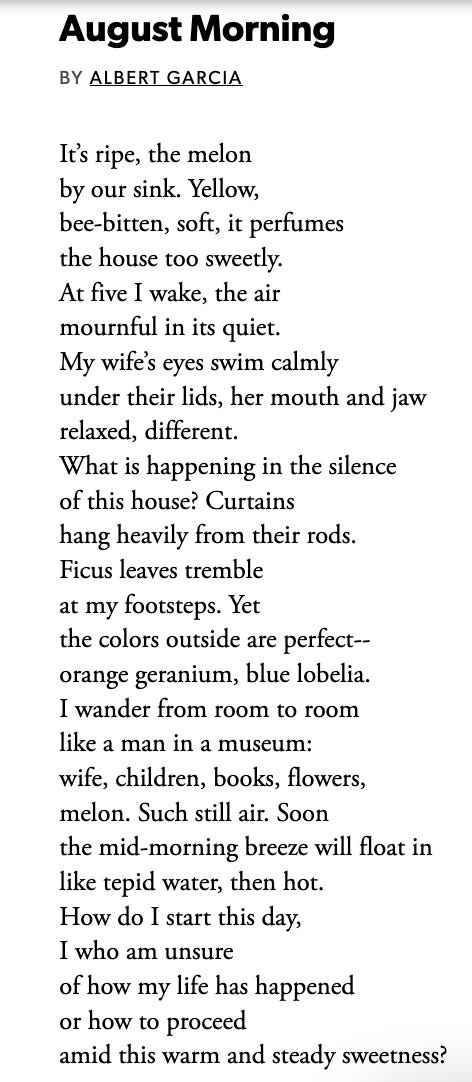

I have been reading poetry every day, a kind of training. I’m trying to learn about poetry. I have been learning about poetry for more than thirty years, twenty years in formal ways, and I feel more and more bewildered by it. How does it do it? How can some people be so sure about it? What would it be like, to be one of those people who is sure about poetry? I feel like I am always just asking about poetry: what, what, what, what, what; how, how, how? I spent a week in July with other poets and every morning the teaching poet gave the group a single poem to read closely. We spent about forty minutes on it, usually, and I could have spent three hours—or the whole day—doing just that close reading. I love this thing called poetry, even though I don’t understand it, I love to do it with other people, and I have no idea how I would go about understanding something so big. So August has been poems and blackberries for me, the latter catching my clothes on their thorns as I reach in to pick ripe fruit. The former always already caught on my clothes.

While walking through this cool and damp summer I have had the syncopated knowledge that in so many places this summer has been terrifyingly hot. I’ve felt sick with the knowledge of heat and drought and fire, floods and crop losses, fear and suffering and death—human and nonhuman beings, and the land and the ways of living on and being in those places. When I am afraid I often feel immobilized by that fear and by the immensity of things like the catastrophes of capitalism, imperialism, settler colonialism, plastic, petrochemicals, ‘forever’ chemicals—the ruin of whole worlds, ways of being, possibilities for relation, already in action. The sense of my smallness and the problems’ largeness quickly spirals in two directions. What could I possibly do? What do I have to offer? My life feels very tiny, short, and ineffectual then. And yet life is what we have, each of us and all of us. Not only our individual lives, but our shared one, too. When I remember this I feel immense gratitude for labor unions and workers (and students!) who are striking or have used strike threats to get fairer contracts and safer working conditions—and to remind us what we can ask for and must ask for, and to remind us that we cannot do it alone, and we are not alone.

A model for the present and the future, strikes teach me that we can make sacrifices together that, when we do make them together, feel like joy. Strikes remind me we are together. Our daily lives have to change. That’s a fact. And we can only make that change together—the details may differ from place to place, but the fact remains that we can only do it with other people. We need, we cannot live without, a change that insists that those who cheapen and discard all of life and all the land, water, air desist: militarized nations, massive corporations, massive tech. Our lives are not cheap—none of them, not the lives of the ones who face buoys made of saw blades in border rivers; not the lives of the ones who embark on unbearable journeys in insufficient crafts; not the lives of the ones snipping threads in clothing factories that run day and night, or of the ones carrying ore from a mine, or of the ones packing boxes under the eye of a computer timer in a warehouse. Not the lives of the ones who fly or of the ones who photosynthesize.

We can change our lives together, for one another. The urgency is huge. We are faced with the facts—the exclusionary, unjust, entrapping facts—of landlords’ hoarding and of billionaires’ death-driving. But we don’t have to accept these facts. There is no outside to the circle if we insist there is not. We can set down our tools, close our laptops, park our cars, and walk into the street together, hand in hand, arm in arm, shoulder by shoulder, singing. We can strike from our everyday lives. (I am still in awe and wonder at the self-immolation of Wynn Bruce. How do I live as committedly as that?) What happens if we do strike from our everyday lives, our habits of knowing and doing and being? What happens if we step, for a moment, together, into a new possibility? (Ruby Dee: “[The songs of the civil rights movement] became almost as common as love songs. And also—direction songs.”) Direction songs. We aren’t the first people doing this. If we sing together? Sing instead of shopping? Sing instead of working?

A strike is holy. That’s why it’s hard—holy things feel impossible on the one hand, and maybe almost silly on the other. But looking one other person in the eye and joining them—we will find it is not silly at all, or difficult, at all. There we are. Together.

I think that sense of holiness is a name for what happens when people do something together that departs from the “just how the world is” of the world in order to insist on beauty, dignity, care for the world and its beings, the value-as-such and -in-such of land/water/air/all life. Invention and daring in service to shared life. I haven’t figured this all out but that feeling of holiness is part of why I want to pay attention to poetry—its how more than its why or even its what—and to blackberries and all the other ‘minor’ (not minor!) indices of time and place. The closer I look the more I know: we are here together. Meaning happens amid the smallest movements and by the most minuscule differences. Everything is precious. I’ve said that before, I’ll surely say it again, because it is the simple thesis of the world as I’ve encountered it. There is no living thing that is not bound up in our shared existence. If we mean, we mean together.

What have I learned, reading poetry and walking, looking at and picking blackberries in neglected lots this August? Thinking takes place over time—I knew it, but I have to learn it again and again. A poem is sometimes the accretion of meaning across a duration rather than the crystallization of an image within a form that can be held in the hand. The most basic, incontrovertible fact of life is that we are bound up together in it, and that one thing that poetry, music, art can do—not necessarily, and not always, but it’s possible—is remind us of that fact, and of our responsibility to one another. (Need something to carry you there? Here’s Sister Rosetta Tharpe with a lesson. And here’s Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee with another version of the same.)

Beauty is the lesson we can never finish learning. Whole, open, for everyone. Like poetry, we can spend our lives on it. It’s not simple—it’s deeply complex. It’s not reserved; it’s for everyone, always. It’s not esoteric, it’s here, right here, at our fingertips, again and again, every day. It’s the fact of our intense, intricate co-relation, unfolding.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite poems, one I think is probably on a lot of people’s list of favorites. It’s a poem I was given by a teacher when I was about 22 and it is still mysterious to me. In every season it’s given me something new. I still don’t fully understand how it does what it does, or all that it does. But it does remind me that the world is a shared one—the world of blackberries and beloveds—and that one thing poetry can do is try to speak and spell exactly that complexity, one letter at a time, one poem at a time, until, along with the everything-elseness of the world, we have made and continue to make the world in which we can all live.

Thank you for reading. See you in a week!

For me, poetry is making music from speechlessness. There’s quiet and failure and craft and patience, and then something happens. And then you let it go.

I think we’ve damaged ourselves because of what we refuse to let go, what we insist on trying to own or control rather than regard with gratitude and joy. What we now want to hoard. This includes nature and one another. The more we insist on holding with our fists, the more our fear grows. Before we can build truth, community, we have to let go.