From about the middle of March, 2020, until about the start of the new year, 2022, I could hardly read—or, couldn’t read the way I was used to. Why? It’s too undifferentiated to say “the pandemic”, when what I mean is “mass death as well as particular deaths” and “the awareness of stratified classes of more and less expendable workers” and “migraines from wearing an N-95 for twelve hours of commuting and teaching” and “the police station in my childhood neighborhood on fire!” and “the unsettling joy of seeing crowds in my home city, marching, but only via internet” and “moving yet again for uncertain employment” and “emails with landlords arranging to view apartments we couldn’t afford, by video chat”, as well as meaning “parental illness” and “underemployment and short-term contracts” and “expensive, freezing, poorly maintained rental housing” and “coping with loneliness” and “mortality” and “grief as mass death was normalized”. Even that list is too undifferentiated. What I am trying to say is that over those twenty or so months I learned how bodily stress is: how there really are thresholds beyond which it is impossible to read, concentrate, write more than a sentence or a fragment of a sentence. I felt like I was losing an important part of my mind. I felt like I would never read anything again, much less write anything. I sometimes felt that didn’t matter. I felt I was inside a thick layer of wool, from which no sound would emerge.

Reading came back slowly in early 2022. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I started being able to read with more coherence and comprehension at the point when I accepted a job with some stability in the mid-term and we began to make plans to leave a place and jobs that were really soul-killing for both of us. Being able to read didn’t come back all at once: I had to teach myself to sit with a book. I couldn’t read with music on. I sometimes set a timer and forced myself to read for twenty minutes at a time. Training. It was a huge relief to be able to pay attention, sustain immersion in someone else’s thought. The lesson in what stress can do to that ability helps me think about my students as well. It is impossible to think well, much less read something complex, under existential strain.

At the moment I live in a city, in a country, with a robust public library system. Books travel across the country to me. I can request almost anything and have it show up within walking distance in a few weeks. And the university library supplies me most of what I can’t find at the public library. Going to the library feels like childhood: the pleasure of choosing things, finding things I’ve been wanting! to read, finding things that surprise me. The deadline: three weeks to read them, and then back they go. The smell of the public library and the university library. I love it. It is in part the library that has given me reading again, because the due date requires me to commit. Twenty minutes in the morning, or a chapter at breakfast and one at lunch, or an hour in the evening, or a section at bedtime.

The library lets me pick things up I might not have—long schooled in the careful accounting of contingent and short-term contracts, I rarely buy books. But the library permits me to be catholic in my acquisitions. It lets me put things down when I find them insufficiently thoughtful, or not to my current liking, or dull. It’s also helped me remember that I have preferences and tastes, and to begin again to describe those to myself, which in turn lets me think about what I’m writing and where it belongs. Once, a male writer told me that my writing was “too philosophical” to be poetry or literary nonfiction. I have thought about that for years now. What does that mean? What was he trying to say about writing, about poetry, about essays, about philosophy? What is “too” in that case? As I read and set aside books from the library I realized that the books I most thrill to, think about after reading, want to write in the company of are those “too” books, the ones that refuse to stay inside polite lines or that critique or refuse the ‘politeness’ of those lines.

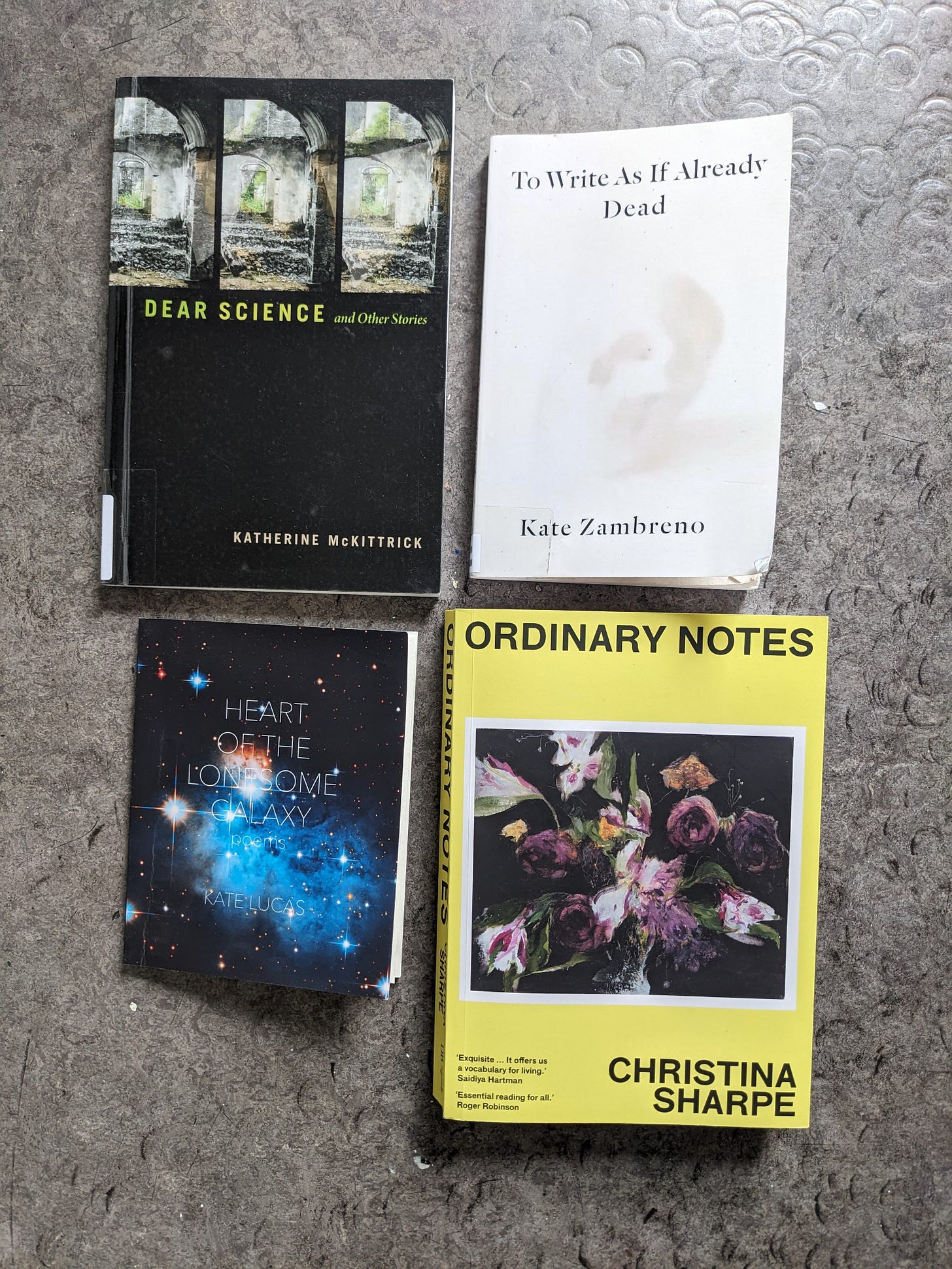

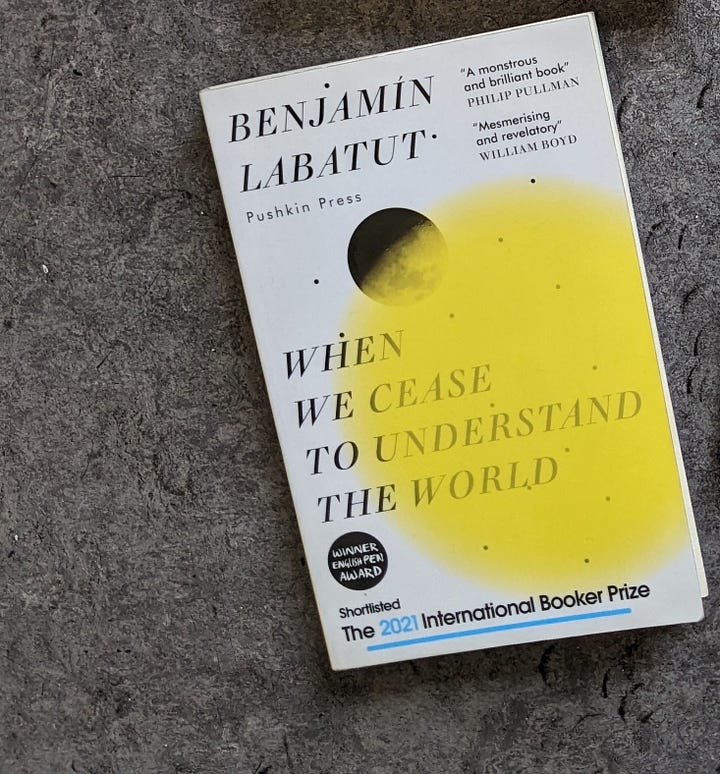

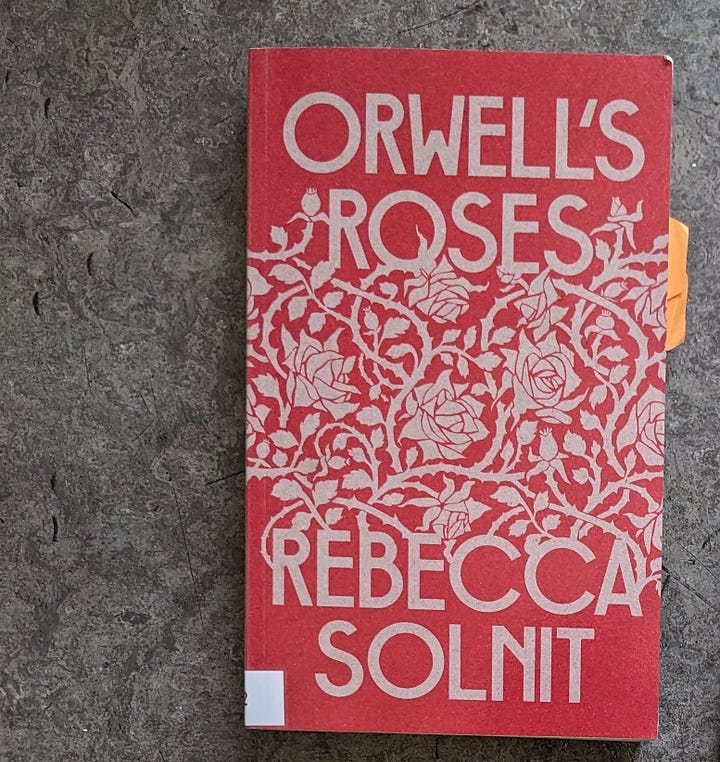

Some books I have loved lately, in order of their authors’ last names: Benjamín Labatut, When We Cease to Understand the World (translated by Adrian Nathan West); Kate Lucas, Heart of the Lonesome Galaxy; Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories; Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes; Rebecca Solnit, Orwell’s Roses; and Kate Zambreno, To Write As If Already Dead. Very brief notes on these books are below—not reviews, and by no means complete, I hope that they might convince you to read them (and to ask your local library to please get a copy).

Solnit: a pleasure to read. Richness and variety of research, sturdy and steady insistence on complexity over flatness or immediacy. Labatut: I love the mobile imagination, the treatment of the 'real' as a way to make fiction (physics, chemistry, math...and also destruction, gardens, desire, competition, human shortsightedness, war, history...). McKittrick: giving me so much language for ways of writing and studying; so smart and dense and formally curious. Sharpe: this will enter my shelf of ideal books. Many-stranded, deeply subtle, attentive, complex, tender (!), insistent, moving, joyful and brilliant; made me want to reread In The Wake: On Blackness and Being. Lucas: handles metaphor so well, over the extended form of the chapbook; a really gentle but unflinching gaze at family history and violence. Zambreno: goddamn ambitious and capacious and smart and moving, this book made writing wider. Actually all these books do. They returned to me not only some of the pleasure of reading and the work of attention, but also the sense of writing in company. Including yours. Thanks for reading.