moving, finding housing, finding furniture. giving up furniture you loved. (“the art of losing isn’t hard to master”!) giving away books. driving across the continent, or flying across the ocean. the calculus of how fast your parents and siblings age vs. the chance that this job might turn into something permanent. working on job market materials several hours a day after you do your full day of teaching and grading. learning a new town, again. figuring out public transit, again. first and last month’s rent, again. security deposit, again. being asked the question “why haven’t you been able to buy?” and having to come up with an answer that won’t be a downer, though it is a downer! biting your tongue about the truth of your life in social situations with your new colleagues, again. choosing between the work you’re trained for and staying somewhere. the strange disjunct of being in your 40s and having no permanent place to live. packing up the apartment, again. giving up a garden you made.

the time it takes to find who does what at a new institution, not to mention figure out what the students’ backgrounds are, how the course rotation really works, and what the actual expectations are (as opposed to what you’re sold in a job interview or given to understand by implication by your more secure colleagues). doing that again, in a new institution, the next year. hearing tenured and TT-colleagues say things like, “well you knew what the market was like when you went on it”. hearing them say things like, “you probably would have had a child by now if you were going to, right?”. a dozen interviews, if you’re lucky, each with their own preparations (hours and hours), sometimes on as little as two days’ notice. moving again.

learning the copy code, the door code, the program assistant’s name, the invisible and unstated hierarchies, the map of the building, the map of the campus. switching health insurance again (how many hours per year trying to figure out which plan will not bankrupt you?). trying to find a primary care doctor in your new town. paying for another ‘new patient’ appointment because you moved, again. chasing down 1099s and W2s. looking up your password from two institutions ago so you can log into HR and get said tax paperwork. no you don’t have access to the 403b as a temporary employee. spend an hour on the phone trying to figure out whether you can open a Roth IRA. retirement? what’s that?

dealing with another new landlord.

extra trips to the grocery store every week (your total grocery bill for the month will be higher, not to mention the time it takes to go more than once) because you live in a rented place, in a town where there are few places for rent, and your landlord has decided a dorm-size fridge is sufficient. you want to have a baby? if your contract is one year only, be sure to stress out before the start of the semester trying to get pregnant so you’ll give birth while you still have health insurance. if you have a nine-month contract and forget to ask HR about spreading nine months’ pay over twelve months when you sign, your salary will end when teaching does, in April or early May, and you won’t get paid again until September (or October, even, if you have transferred institutions).

not buying new clothes even if yours have holes because groceries, rent, and emergency fund come first. “I’ll patch them” (count the time it takes to patch a garment). feeling shabby around your colleagues. going to therapy ($185 copay per one-hour session) and spending half the session working out why you have imposter syndrome when you publish and teach and study how to teach better and do service and go to conferences (when you can afford it), just like your colleagues. being told you don’t qualify to join the union because you’re an adjunct. being told you can’t apply for any research funding because you’re on a one-year contract, despite the funding applications having no stated policy against that. teaching for eighteen (!) years in a row, more or less, without a sabbatical.

repeatedly emailing your landlord to make sure you get your deposit back. paying for another year of mail forwarding. sending an email to everyone you can think of who owes you money, a tax form, or something similar to let them know how to reach you this year. less borrowing power when you finally do get a mortgage because you are now “too old”, i.e. too close to death and/or the poverty of “retirement” (!) to be a reliable repayer. “rent payments do not count toward a credit score.” the filing cabinet full of courses you got to teach once. the weeks and weeks of prep for courses you agreed to cover on demand but aren’t a specialist in. call around to find a therapist in your new town who accepts your insurance. wait for an appointment. tell the groundwork story again ($185 copay per hour session, remember?). write an email to your recommenders asking them to update their letters for another year.

Those are some facts. They come, mostly, from my life. I love my life, it should be said. I love to talk about literature with students, and help students come to a rich, beautiful, complex understanding of writing, and life, and art.

Some of these facts come from the lives of friends and former colleagues. They are the often invisible truth of what it means to be a non-tenure-track college teacher. They are more-or-less the case whether we are working in the U.S. or U.K. or elsewhere (though access to things like pension, healthcare, etc., may differ outside of the U.S.). And the facts are shameful, and would be shameful facts for workers in any industry. Indeed these facts are shared across many industries, though the one I know is the college teaching industry.

The facts are shameful and they are destructive of life—the life we all share. Human beings need stability, placedness, dignity in work, belonging.

In the U.S., more than 75% of college teachers are off the tenure track.1 In immediate terms, this means that most of the people who are academic experts in their fields, who love to teach young adults, who represent the future of higher education in the U.S., have no future there at all. Many adjunct, contingent, non-tenure-track, non-permanent, affiliate, or contract faculty (however they’re designated, it means more or less the same thing—lack of stability, lower pay, often no health insurance or other benefits, including pension, access to sabbaticals/research leave/funding) live at or below the poverty line.2 Some college teachers, including graduate students—who are also college teachers without stability, permanency, institutional power, or prestige—are on food stamps.3 Harvard University’s endowment is at least $53 billion4 (with. a. b.) as of 2021. In 2023, the Harvard University Graduate Health Services sent out a flyer explaining how graduate students could sign up for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which you might know more familiarly as food stamps.5

These are the conditions under which contingent college teachers work. I worked under these conditions until very recently (I now have a job with a four-year contract, so some, though not all, of these conditions are mitigated). Contingent college teachers share these conditions with all kinds of workers: in food service, in grocery stores, in delivery vans and on delivery bicycles, in warehouses, doing gig labor to run errands or retrieve groceries, cleaning houses and offices and university buildings, serving food or preparing it, teaching young children. These are not the conditions of a rich life but of a bare one. They are not the conditions under which we can—and I mean all of us, any of us—really fulfill our human remit, which is to be creatively alive, to make worlds together, to dream, to change with and for each other.

How is this right?

How is this liberating?

How is this good for students?

How is this sustainable?

How does this serve us as humans, on this earth with other humans and non-humans?

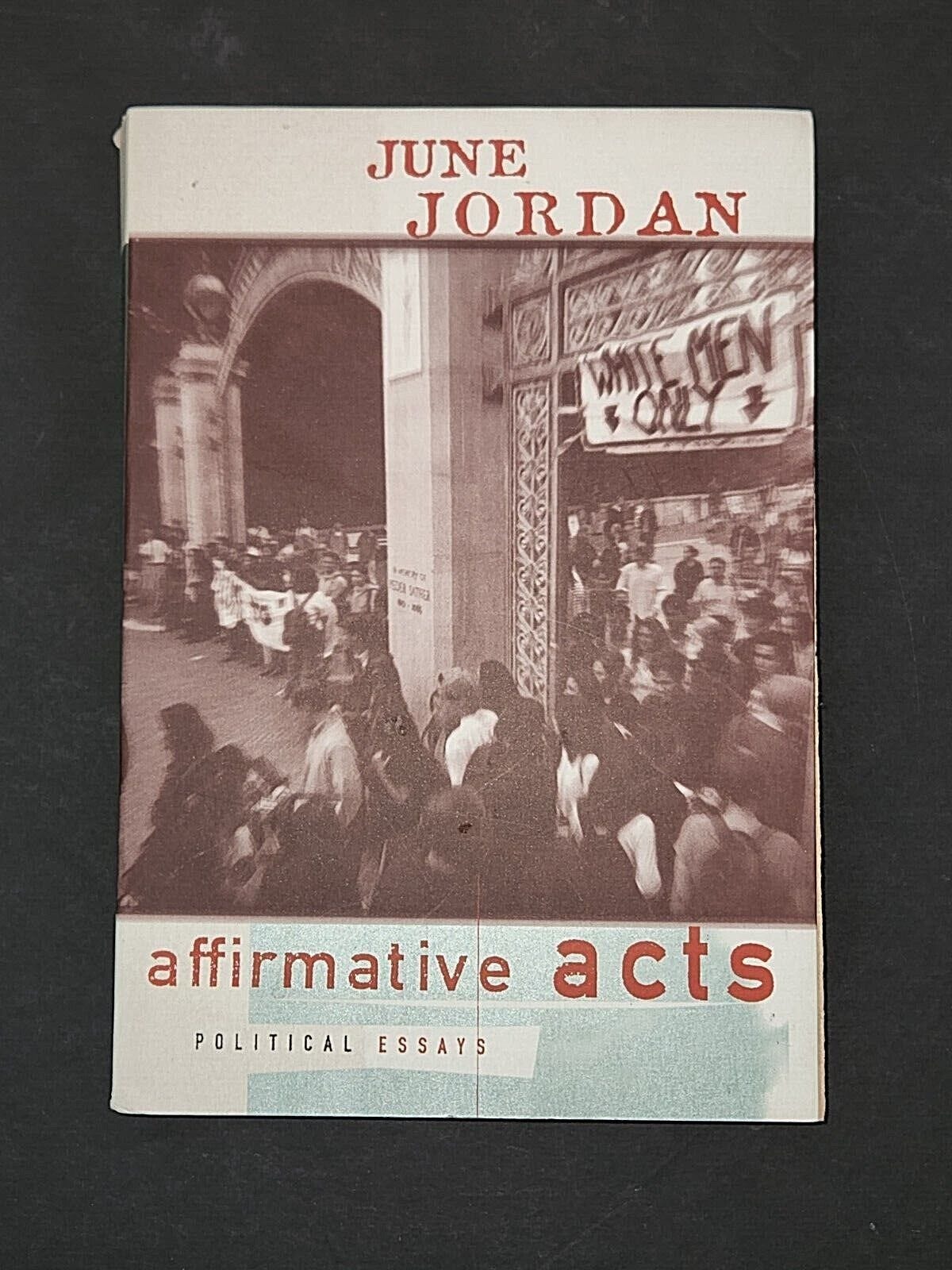

Recently I read June Jordan’s 1998 book Affirmative Acts. Jordan was a poet and teacher who lived and worked in the Bay Area of California in the 20th century. That sentence is insufficient; all I could write would be insufficient. You can read her work and read about her life, but here’s a glimpse: she founded Poetry for the People; she wrote without ceasing against and through the linked horrors of U.S. racism and U.S. militarism; she contributed what are to me two of the richest sources of thought on the U.S. poetic tradition. Her book Some of Us Did Not Die has for a decade been a touchstone for me as a thinker, be-er, writer. Anyway, this is to frame in the texture and tangent of Jordan’s thought for you, so you might understand why, in the context of what precarious work costs, I so needed to read her at this moment.

What Jordan reminded me of, in her essay called “The Revolution Now: Update on the Beloved Community”, is the liberating, motivating, joyful solidarity to be found among others, when we use our bodies together and for one another. It’s palpable in images of the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis in 1968—the posture of the picketers!—and in images of contemporary strikes. It’s there in the sound of songs where folk tradition and the radical care of the labor and antiracist movements are zipped together. And it’s there in Jordan’s description of her students’ decision to go on hunger strike in response to the 1996 majority vote on California Proposition 209. Jordan writes that “fasting emerged as the collective tactic of choice” when her students were confronted by the passage of 209. Parsing a student’s suggestion of a fast in the mode of Ghandi, Jordan goes on to say that if “evil surrounds you and abounds, and if you eschew violence, and if you, apparently, cannot persuade a majority of folks to vote against what’s wrong, then, perhaps, fasting to death is one appropriate response” (Jordan, 209).

Pause.

Oh—yes. The use of our bodies, alone and, ideally, together, is also an option when confronted with systems that degrade human life and human solidarity. These precious being-objects we also are.

In the essay, Jordan and her students go on to place themselves in a network of nonviolent, active resistance, a network of people—from Palestine to China to Nicaragua to the U.S. and beyond—who have used their bodies, put their bodies in harm’s way, in power’s way, to resist what defiles human life. To defend our shared existence. To stand, literally, with one’s own (and only) body, for one another. A week after the passage of Proposition 209, making affirmative action illegal in California, Jordan’s students “stopped eating […] stopped everything except the commitment of their bodies and their hearts and their minds to the resurrection of Affirmative Action in America” (211).

What beauty.

What beauty, to be with other people, “keep[ing] faith in what they believe is right” and “to have emerged, exhausted/sick/confused/but to have emerged/as a collective, in fact”(213).

I needed to be reminded, thank you June Jordan, thank you, her students, that our human bodies are real and can be used, together, against great harm. And that even one such body so acting can “embolden and inspire other[s]” (213). I needed to be reminded that knowing we are not the first, and not alone, can make us braver—for and with one another. And that, as Pete Seeger often said, this is work that takes, like singing does, hands and hearts and heads to do it; human beings to do it.

I don’t have a place to go, here at the end of this. Except that it’s easy, in the rushing overwhelm of trying to stay afloat, for me to forget that I’m not alone and that I have a lever—my own body, my own life, my hands and heart and head—against what I hate: casualization and precaritization and vocational awe used against workers, and capitalism and resource hoarding and the cheapening of what is most precious (our lives).

To know how long so many people have been working against this is a preventative treatment for despair. We are not alone. We are with one another: with all of the one-another of the others near us, who though they may be unlike us in some ways are also taxed by the precarity that makes our lives cheaper and a few people (and institutions) very very rich. June Jordan, and her students, remind me that it matters to know that history of people working, with their bodies, together, for liberation. It matters in deep ways, living ways. It, some days, keeps me alive.

So. Against precarity; for one another; with roses cut from our gardens and loaves of bread we made, that always feed one more than we estimate they would.

Happy May Day for tomorrow. Thanks for being here.

New Faculty Majority, with statistics from the U.S. Department of Education. https://www.newfacultymajority.info/facts-about-adjuncts/#:~:text=Vital%20Statistics,often%20known%20as%20%E2%80%9Cadjunct.%E2%80%9D

Flaherty, Colleen. “Barely Getting By”. Inside Higher Ed, April 20, 2020. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/20/new-report-says-many-adjuncts-make-less-3500-course-and-25000-year

“Why So Many Ph.D.s Are On Food Stamps”. NPR, May 5, 2015. https://www.npr.org/2012/05/15/152751116/why-so-many-ph-d-s-are-on-food-stamps

“Harvard University Endowment”, Wikipedia. Accessed April 17, 2023.

Roscoe, Jules. “Harvard Tells Grad Students to Get Food Stamps to Supplement The Unlivable Wages It Pays Them”. Vice News, March 30, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/93kwaa/harvard-tells-grad-students-to-get-food-stamps-to-supplement-the-unlivable-wages-it-pays-them