In my earliest memories we are walking together. We are walking together along the sidewalk, wall on one side, street on the other. We are carrying banners. We are carrying signs. We are in strollers or pushing strollers; we are carrying babies. We have mobility aids, we are using wheelchairs, we are helping one another walk, we are striding forward with the people we love and with people we don’t know. We are under the white-gray sky of an upper Midwest January, and it is ten degrees below zero Fahrenheit and it is too cold to snow and here we are: walking. We are walking toward the state capitol building, all of us, together, hundreds of people, sometimes thousands of people. We do this over and over, weekly, monthly, for years. We do it despite the fact that there is no directly attributable change because of it. We show up and we walk together. It is cold, it is uncomfortable, it can be tiresome, there are more immediately pleasurable things to do. But once we get close, once we hear the crowd and see the banners and the signs, we know again: there is no better place to be.

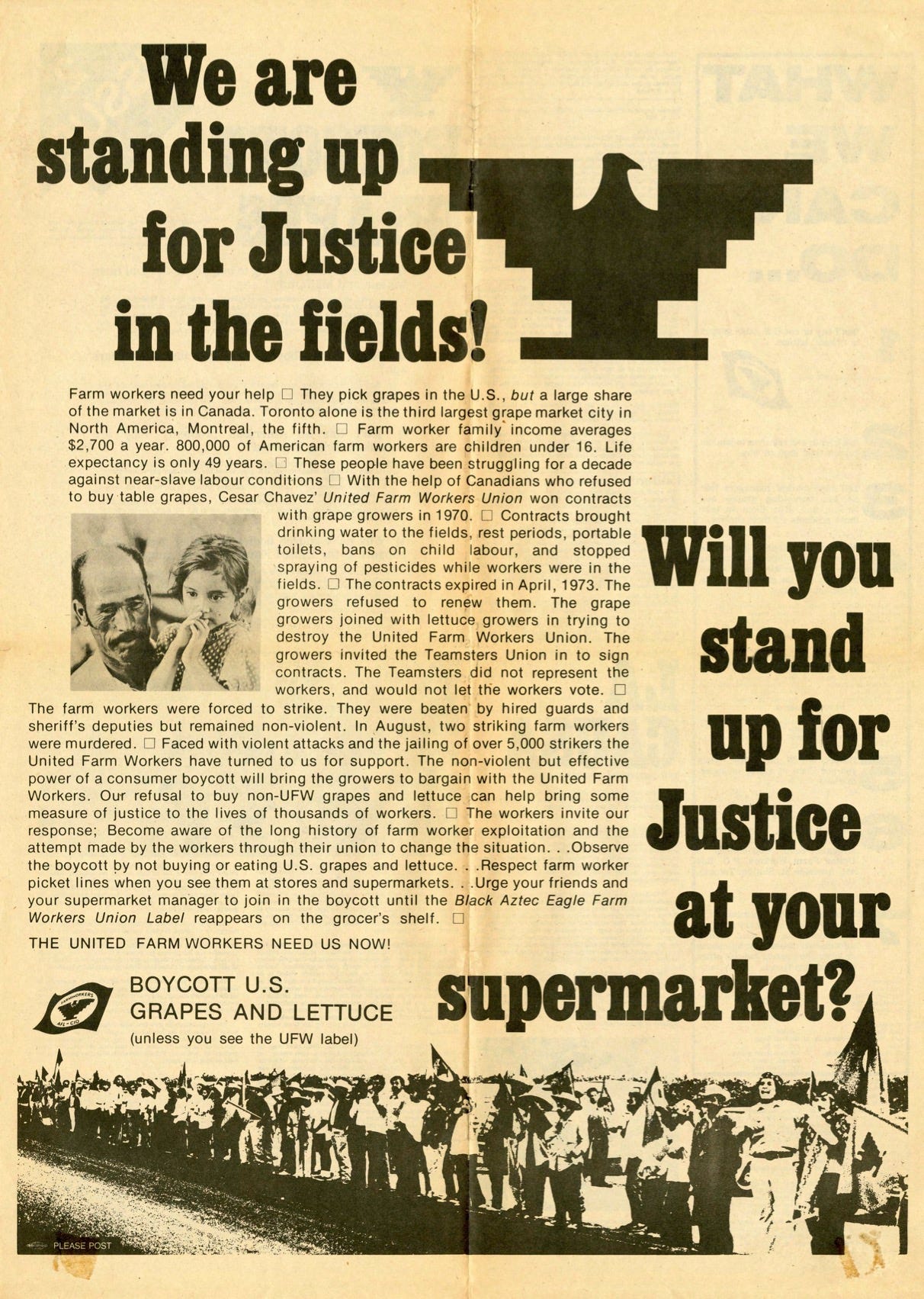

Nuclear freeze marches and rallies. Grape and lettuce boycotts. Chocolate and formula and cereal boycotts. Women holding anti-war signs every week for decades on a bridge over the Mississippi River. Nuns jailed for protesting torture schools funded and exported by the US government. Teenagers and elderly people blockading the driveways of the arms manufacturer. Teachers’ union strikes and farmworkers’ strikes, anti-apartheid strikes. Anti-war march after anti-war march. Free stores and soup suppers. Folk concerts at the local college and in the public park, in the train station. City buses and bicycle lanes. Student strikes, graduate teaching/research assistant strikes, university staff strikes. Occupy. Sleepouts with unhoused neighbors. Underground abortion networks and abortion funds. Act Up posters made on kitchen tables, zines reproduced at copy machines. Curb cuts at every corner, walk signs that we can hear as well as see.

If these actions do not appear on the map it is not because they don’t take place, it is because they do, but their accretion over time, the accretion of their effects over time, is minuscule and subversive and those effects weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life, such that it can be taken for granted that some of us now have weekends and the right to unionize, that certain pesticides and herbicides are banned, that some kinds of equitable access to buildings and institutions are available. And there is still time for more of these minute actions, for example because there are still workers whose hands prune apple trees in freezing January temperatures and who breathe in soot in summer fire season, and there are still new weapons being developed and tested. There is still work to do, and we are the ones to do it. And it is, still, “always too soon to go home”, words I take from Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark, her prismatic collection of essays on the ends and beginnings of the world. Does it sound like a lot of work? It is a lot of work, but we are a lot of people and we have our whole lives, every single minute of them, for it.

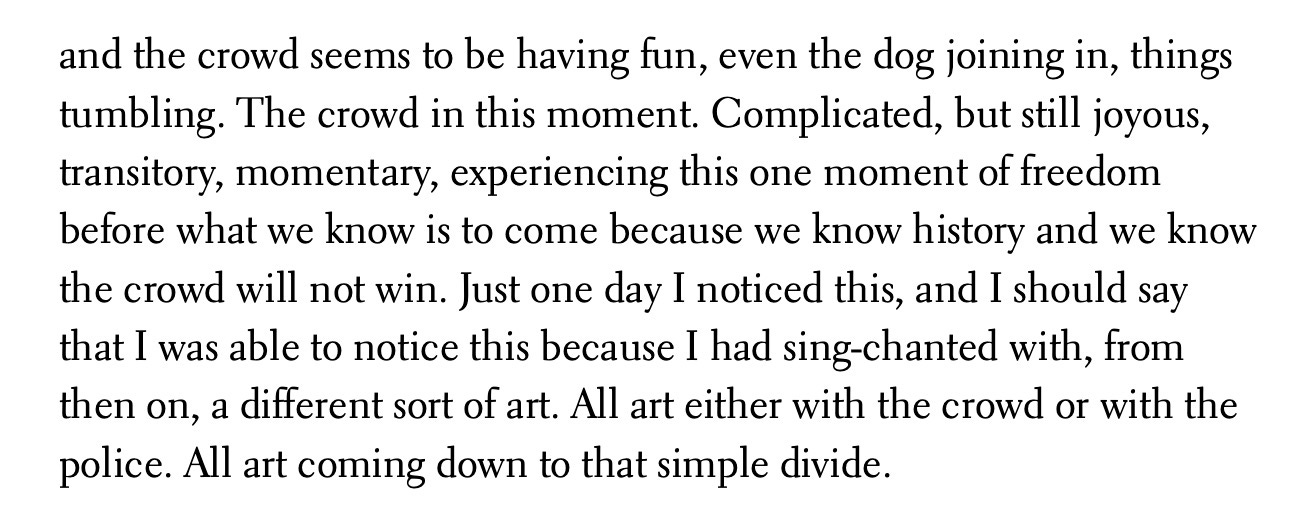

On the side of life is every action, no matter how small, that helps to make a rich life, a free life, possible for everyone, in concentric rings of solidarity and care. The rings say: we are involved with each other. You are mine; I am yours. The specifics are specific to our places, relationships, points in time, knowledge, needs and abilities. A general answer or a single strategy is unfit for the specifics of our lives—responses have to be worked out, over and over, in time and space, among and between us; the complex demands of living in this world with others require modesty and humility and patience and attention and ongoing work and a cheerfulness that is not optimism but a willingness to be honest about both history and the present. To me the guide is: does something make a rich life, free life, more possible, for more than only me? There are no heroic acts in this frame, no one-and-done solutions; there are only the tiny, continuous trueings of a compass both personal and social to the north star of no one is free until everyone is free.

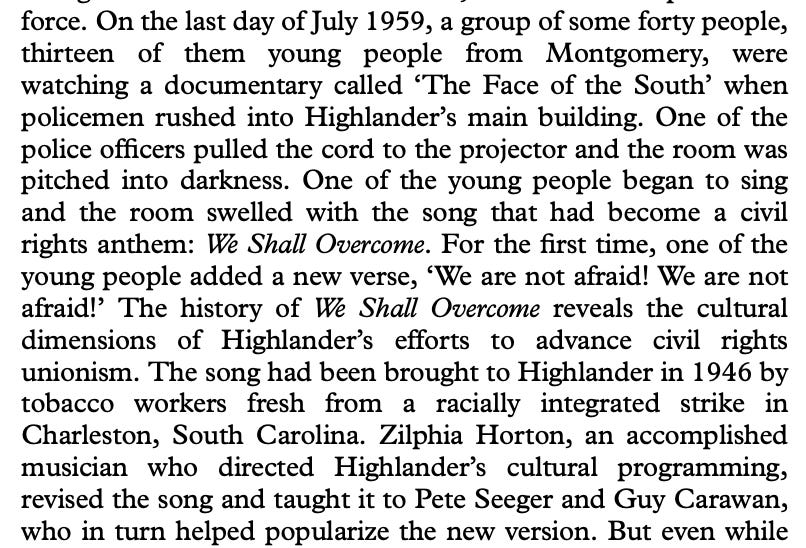

That is not a burden, that is a pleasure. That is meaningful work, a lifetime’s worth. That is a joy. That is freeing. That is why it makes sense to me that marches beget artwork, and artists appear at marches, why singing together at the protest feels good and dancing at the labor strike creates good feeling that translates into good action. That is why it surprises me when community care in the form of public mask-wearing gets framed as fear or even paranoia. I want to say, don’t you realize? The song has the words right in it! It couldn’t be clearer. We are not afraid.1 We are in love. The world and its people are the ones for us. Your grandmother is my grandmother. Your lungs are my lungs.

We are out here together, for one another, with every step in the bracing air, making every tiny refusal, hearing every “why would you do that when it doesn’t even matter”, saying, yes, in fact, it does matter; it does matter to refuse death as best I can—not for myself alone but for my neighbor, including the neighbor I don’t know or can’t see; saying yes, in fact, it does matter to make myself a tiny bit uncomfortable (January freeze march, Minnesota; never having a Nestlé candy bar in childhood; no grapes until adolescence; not crossing a picket line; Black Lives Matter pin bought in 2016 still on my bag despite the hot embarrassment I felt on my face when another white lady in the grocery store line said “isn’t that over?” in 2022; and yes, wearing a mask in public spaces right now—your responses may vary) if it makes someone else a tiny bit more comfortable or our life together a little more possible; saying yes, in fact, we are here together, breathing the same air, drinking the same water, walking on the same streets, waiting for the same bus; saying that the trees you prune become my bone and my blood, that the radioactivity falling from your sky after our missile test becomes the milk I give my children.

When we say, feed the hungry, we mean ourselves as well: we are the hungry. When we say, make a world where to be sick is not to be closed off from that world, we mean ourselves: we are the ones with bodies that can be ill, can be disabled; we are the ones who age. When we say no police we mean anywhere. There is no other world, there is no other life, no other air, no other water. It is all between us. No time to waste in beginning together the work of worldmaking that is at hand. No work too small to matter, nothing so important it can’t be repeated again tomorrow. No need to wait before discovering the secret of joy.

Thanks for reading. See you next week.

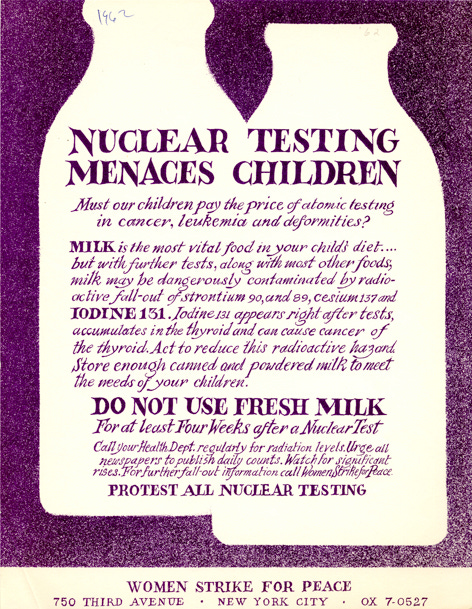

To be clear, I’m by no means making an equivalence between the ongoing movement for Black civil rights in the US and the discomfort of being, often, the only person in a room of artists or scholars wearing a mask during an ongoing, airborne pandemic. These are not the same thing. But I have learned this framing—of joy, of solidarity, and of refusal of fear—from this movement among others. I have also learned to be skeptical of the demand to see a difference in focus among movements for a just, free, safe, healthy, and joyful life as indicative of disjunction between movements. And in fact, leaders of that civil rights movement saw clearly how things like nuclear arms were involved with, not separate from, voting, housing, dignified working conditions, access to public space, education, healthcare. This is all about our obligation to provide for one another a rich, free life.

![It's always too soon to go home. And it's always too soon to calculate effect. I once read an anecdote by someone in Women Strike for Peace (WSP), the first great antinuclear movement in the United States, the one that did contribute to a major victory: the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which brought about the end of aboveground testing of nuclear weapons and of much of the radioactive fallout that was showing up in mother's milk and baby teeth. (And WSP contributed to the fall of the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC], the Department of Homeland Security of its day. Positioning them- selves as housewives and using humor as their weapon, they made HUAC's anticommunist interrogations ridiculous.) The woman from WSP told of how foolish and futile she felt standing in the rain one morning protesting at the Kennedy White House. Years later she heard Dr. Benjamin Spock-who had become one of the most high-profile activists on the issue-say that the turning point for him was spotting a small group of women standing in the rain, protesting at the White House. If they were so passionately committed, he thought, he should give the issue more consideration himself. (From Rebecca Solnit's HOPE IN THE DARK, p.3) It's always too soon to go home. And it's always too soon to calculate effect. I once read an anecdote by someone in Women Strike for Peace (WSP), the first great antinuclear movement in the United States, the one that did contribute to a major victory: the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which brought about the end of aboveground testing of nuclear weapons and of much of the radioactive fallout that was showing up in mother's milk and baby teeth. (And WSP contributed to the fall of the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC], the Department of Homeland Security of its day. Positioning them- selves as housewives and using humor as their weapon, they made HUAC's anticommunist interrogations ridiculous.) The woman from WSP told of how foolish and futile she felt standing in the rain one morning protesting at the Kennedy White House. Years later she heard Dr. Benjamin Spock-who had become one of the most high-profile activists on the issue-say that the turning point for him was spotting a small group of women standing in the rain, protesting at the White House. If they were so passionately committed, he thought, he should give the issue more consideration himself. (From Rebecca Solnit's HOPE IN THE DARK, p.3)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc85c8458-4129-41e8-9e5f-663cc531ee1a_2282x1912.png)